Quebec mosque gunman may face 150-year jail sentence

- Published

Aymen Derbali faces a new life after being paralysed in a 2017 Quebec mosque shooting

The man who shot and killed six worshippers in a Quebec City mosque in 2017 is possibly facing one of the harshest sentences in Canada since the country formally abolished the death penalty in 1976. His case is bringing wider scrutiny to sentence "stacking" for people convicted of multiple murders.

Azzedine Soufiane gave his life trying to end a deadly shooting in a Quebec City mosque in January 2017.

The 57-year-old grocer was gunned down while rushing Alexandre Bissonnette as the attacker fired at worshippers.

Six men were murdered that night: Soufiane, 57, Khaled Belkacemi, 60, Abdelkrim Hassane, 41, Mamadou Tanou Barry, 42, Ibrahima Barry, 39, and Aboubaker Thabti, 44.

Soufiane's selfless act - one of several moments of raw courage by those in the mosque that night - was captured in surveillance video from the Quebec Islamic Cultural Centre and shown in court this month during Bissonnette's sentencing hearing.

In March, the 28-year-old Quebec man pleaded guilty to six counts of first-degree murder and six of attempted murder. He faces between 25 and 150 years in jail.

Alexandre Bissonnette arrives at the court house in Quebec City

It could potentially be the longest prison sentence handed down in Canada's history.

Prosecutors are asking "for a sentence that reflects the magnitude of the crime, external committed and the consequences of the tragic events".

A first-degree murder conviction in Canada carries an automatic life sentence with no chance of parole for 25 years.

Lawyers for the 28-year-old Canadian man say if he is sentenced to 25 consecutive years for each murder it would essentially be death by incarceration.

In 2011, Canadian law was amended to allow judges to impose consecutive, instead of just concurrent, 10- or 25-year sentences with no parole eligibility for multiple murders.

In doing so, Canada joined a number of countries that allow - with varying limits and caps - for controversial consecutive sentencing, or "charge stacking".

The change to the law was cheered by victims' rights groups, and the section has been used a handful of times since.

The Quebec City Courthouse

Bissonnette's lawyers have filed a legal challenge against the section, arguing it is unconstitutional.

Theirs will one of roughly 18 challenges to the section that have ended up before the courts since 2011.

University of Calgary law professor Lisa Silver says she expects the issue to eventually end up being weighed by Canada's Supreme Court.

She points to a February ruling by Alberta judge Eric Macklin, external, who declined to give consecutive sentences to a pair of killers who murdered three family members.

In his decision, Justice Macklin laid out his concerns with stacked sentences by noting it is rare for parole boards in Canada to release multiple murderers from jail after 25 years.

He said he was sceptical as to whether increased parole ineligibility for multiple murderers was a useful deterrent.

The Crown is appealing the sentences in that case.

Ms Silver also referenced a decision by Ontario Justice Kenneth Campbell,, external who found the section constitutionally valid, saying it provides judges "a permissive, discretionary jurisdiction to order consecutive parole ineligibility periods in appropriate cases".

Multiple murder cases are often among the most heinous, and stacked sentences tie into some of the most hotly debated issues in the criminal justice system - issues around punishment, rehabilitation, and community and constitutional values, she said.

"This is something for everybody, not just the lawyers, not just the journalists, it's something that society really should be watching closely because it engages a lot of issues," Ms Silver said.

"How do you fit those worst cases with our principles of rehabilitation, proportionality?"

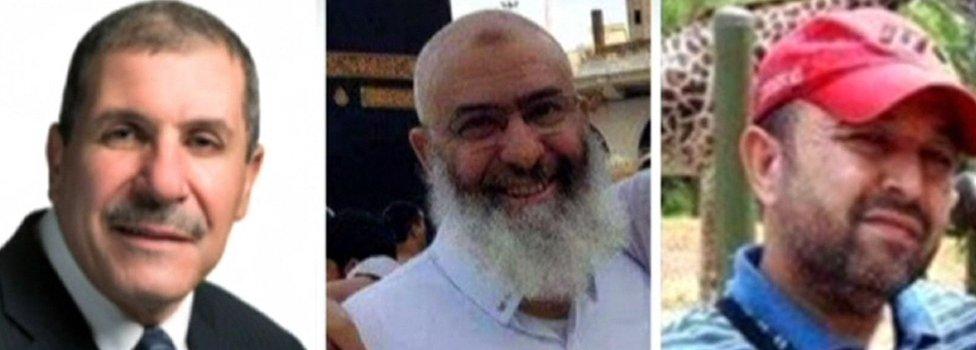

From left to right: Victims Khaled Belkacemi, Azzedine Soufiane, and Aboubaker Thabti

Survivors of Bissonnette's attack and the families of those killed have said both inside and outside the courtroom they do not want lenient sentencing.

They say his punishment should reflect the magnitude of the crime.

"I am certain this man behind me is a monster. And I feel strongly that monsters don't have a place amongst us," Amir Belkacemi, son of victim Khaled Belkacemi, 60, told the court, external.

Louiza Mohamed-Said, wife of victim Abdelkrim Hassane, said the idea that one day Bissonnette would be free from jail terrified her, external.

"When this day comes, it will be a second death for our victims and those who were spared," she said.

Saïd El-Amari was shot in the abdomen and watched his friend Soufiane die as he charged Bissonnette.

He said he did not want his children to live in a society where Bissonnette might one day be a free man.

The day Bissonnette pleaded guilty he said: "I am ashamed of what I did. I am not a terrorist, I am not an Islamophobe."

In a confession to police the day after he stormed into the mosque and opened fire, Bissonnette told police he launched the attack because he feared Canada's immigration policy, external after President Donald Trump's "Muslim ban" and the subsequent safety of his family.

Eight months after the shooting, Bissonnette told a prison social worker: "I could have killed anybody, I wasn't targeting Muslims - I wanted glory".

Mental health experts brought forward by both the prosecution and defence had differing points of view on his chance for rehabilitation.

Sentencing arguments wrapped up this week.

The constitutional challenge by Bissonnette's lawyers is scheduled to be heard in June.

Quebec Superior Court Justice François Huot told Bissonnette he had not ruled out consecutive sentencing, external.

It is unlikely Bissonnette will be sentenced before September.

- Published28 March 2018

- Published13 April 2018