For hire: American tech brains choosing Canada

- Published

Vikram Rangnekar

For decades, Canada has tried to stop top graduates in the so-called STEM fields of science, tech, engineering and math from heading elsewhere for work, mainly to the US. Have the country's immigration policies and emerging tech scene - with some help from US politics - managed to compensate for the "brain drain"?

In 2016, after six years in California working as a software engineer at LinkedIn, Vikram Rangnekar was itching to launch a startup.

India-born Rangnekar was eyeing a move to Singapore - where he founded his first startup - or trying somewhere new like Berlin. He couldn't see himself launching his project in San Francisco with his H-1B visa.

"I could see how the whole immigration thing was going in the US," he said.

Toronto didn't figure into his plans until a chance encounter with a Canadian tech entrepreneur who advised him to look north.

He was told Toronto was the "hidden secret of North America", an underappreciated city with a fast-growing tech ecosystem.

Rangnekar decided to take the chance, landing in Canada's largest city in 2017 with his family.

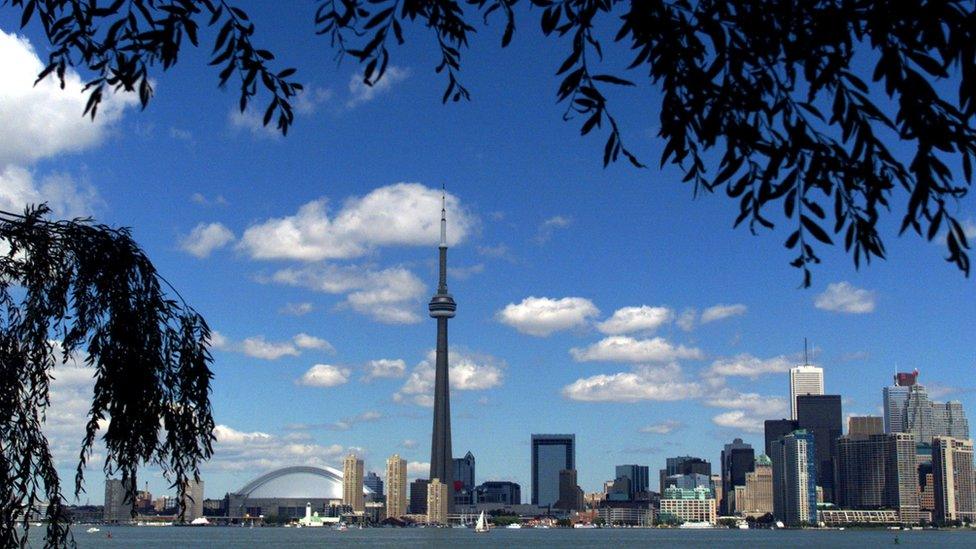

Toronto is experiencing a tech boom

"I had been thinking about working on my own startup idea for while now," he later wrote on his MOV North website, which focuses on promoting the country as an emerging tech powerhouse.

"Getting permanent residency, public-funded healthcare and living in the middle of Canada's tech capital gave me the freedom and courage to explore that option."

That people like Vikram Rangnekar are seeing Canada as a destination doesn't come as a surprise to Vancouver-based immigration lawyer Richard Kurland.

"You've got for Canada a combination of design and circumstance that's setting the stage for a golden age of human capital acquisition," he says.

New immigration policies are making it easier for workers with in-demand skills like Rangnekar to settle in Canada.

In 2015, the country launched its "Express Entry" programme - a free, online process that allows skilled workers to apply to immigrate to Canada.

Kurland calls it a "game changer".

The "Buy America, Hire America" order cracks down on the H-1B visa programme

Under the programme, each qualifying candidate is awarded points based on work, education, language skills, and a handful of other factors. A select number of candidates who score above a certain rank are invited to apply for permanent residence.

"You pick the top scoring individuals - the cream of the cream," Kurland says.

The transparent, points-based system has become a major driver of economic immigration to Canada.

A new work visa that helps companies to quickly hire global talent has also made an impact.

In March, a small survey of high-growth Toronto tech companies by the Mars Discovery District - a public-private tech incubator - found that respondents reported an increase in international interest in working in Canada, as well as a boost in applicants and hires.

PM Justin Trudeau has been pushing to grow Canada's tech sector.

Mars CEO Yung Wu says this survey suggests that "Canada is becoming a destination for the first time in my career instead of a source for talent".

"We had to fight tooth and nail just to keep our teams from being poached by Boston, New York and San Francisco."

Just over half the companies received more international applicants and 45% made more international hires, an interest firms said was driven by immigration policies and the emerging tech scene.

Many firms saw a spike in international interest of 50-100%. Some firms reported a 300% jump.

The top five countries of origin for applicants were the US (82%), India (55%), China (36%), Brazil (27%), and the UK (14%).

US President Donald Trump's H-1B visa crackdowns on India and China also correlated to an increase in applicants from those countries.

The president has targeted the coveted visas - used to place foreign workers in high-skilled US jobs - as part of his "Buy America, Hire America" reforms to ensure they are not used to replace skilled American workers with cheaper overseas counterparts.

In 2017, Toronto was North America's fastest growing tech market. Montreal and Vancouver also have their own emerging tech scenes.

This week, online retail giant Amazon announced it would create 3,000 e-commerce, cloud computing, and machine learning technology jobs in Vancouver.

California or bust

That means Canadian firms need all the talent they can hire.

But even as policy makers made moves to attract highly skilled immigrants, there still aren't enough people to fill the demand.

A 2016 estimate projected the country will be short 220,000 skilled tech workers by 2020.

And Canadian university graduates in the STEM fields are still heading to the US in large numbers.

A recent report out from the University of Toronto, external's Munk School of Global Affairs and Brock University found that 25% of the STEM graduates sampled for the research opted to work outside of Canada, mostly in the US.

Over 65% of software engineering students are leaving Canada.

The graduates are attracted by higher pay - American firms pay up to 30% more - as well as the chance to work with some of the world's largest tech companies.

Respondents also reported student-driven peer pressure to go work for large American tech firms, dubbed the "Cali or bust" maxim.

'Brain Churn'

A LinkedIn Workforce Report from November 2017, external looking at Toronto's labour market suggested the city was gaining employees domestically from Montreal and overseas from India and the United Arab Emirates.

But it lost the most workers to San Francisco, New York City and Los Angeles.

Rangnekar says he's noticed interest in the US and Canadian market flows both ways.

"I meet Canadians here and they're asking me for advice on how to go to the US. I'm advising people in Silicon Valley on how they can move to Canada," he says.

Zachary Spicer, who led the Brock and U of T study, said there is "perhaps a bit of a brain churn" happening as graduates leave for elsewhere and Canadian firms bring people in.

But even with skilled workers coming in, the country loses talent, innovation, and intellectual property when graduates from Canadian universities leave - to the detriment of the economy.

Silicon Valley is a big draw for highly skilled tech talent

Nic Skitt, who is from the UK, was headhunted by founders of a tech startup called "Tickld" and moved to Toronto in 2014.

Like Rangnekar, Canada wasn't originally on his radar. But Skitt fell in love with the city, which he calls metropolitan, safe, and diverse.

"From a practical point of view, the ability to be a tech startup in Toronto is phenomenal. The network of venture capital, of suppliers, designers, general networking is extremely strong," he says.

But Skitt says the company struggled to hire talent.

Competing with the Canadian offices of companies like Google and Facebook for employees, the startup sometimes had to hire "tier two" developers or rely on American freelancers.

"That is one negative in this environment. It's so good a lot of employers are fighting for the same people," says Skitt, who is now with new Toronto-based business MoneyWise.

Kurland says: "There are chronic global shortages and global competition for the brightest and best in key industry sectors of the economy."

"And Canada has to compete against the rest of the world for these workers."

Researchers behind the Brain Drain report say Canada can take steps to stem the tide, like closing the compensation gap and improving promotion of the northern tech scene.

Spicer says the time is ripe for ambitious talent to return and make their mark in Canada.

"I think a lot of firms are ready to blow. The missing component is talent," he said. "We need the sector firing on all cylinders."

- Published2 February 2017

- Published6 February 2017