Jerusalem embassy: Why Trump's move was not about peace

- Published

US opens embassy in Jerusalem

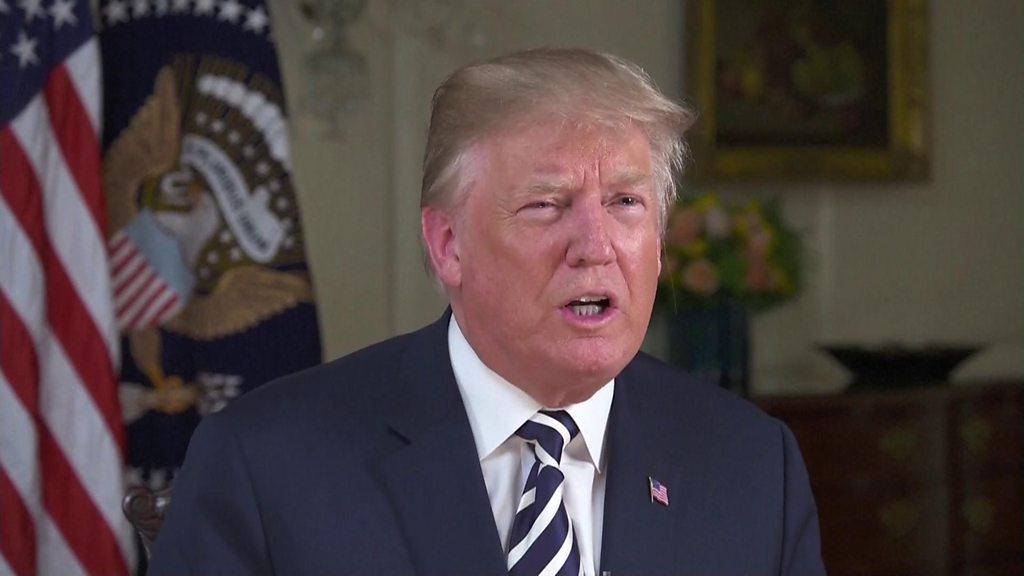

"Our greatest hope is for peace." Those were the words of Donald Trump in a recorded message at the Jerusalem ceremony.

But the opening line in White House talking points cut straight to the top priority: "President Donald J Trump keeps his promise."

Mr Trump decided to move the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem because he likes to keep campaign promises made to his base.

He also likes to make big bold historic moves, especially if that means delivering where his predecessors did not.

So far so good on the principles of Trumpian foreign policy.

In this case, his base also lobbied hard for the move. That included right-wing American Jews whose message was amplified by the conservative orthodox Jews dominating Mr Trump's inner circle.

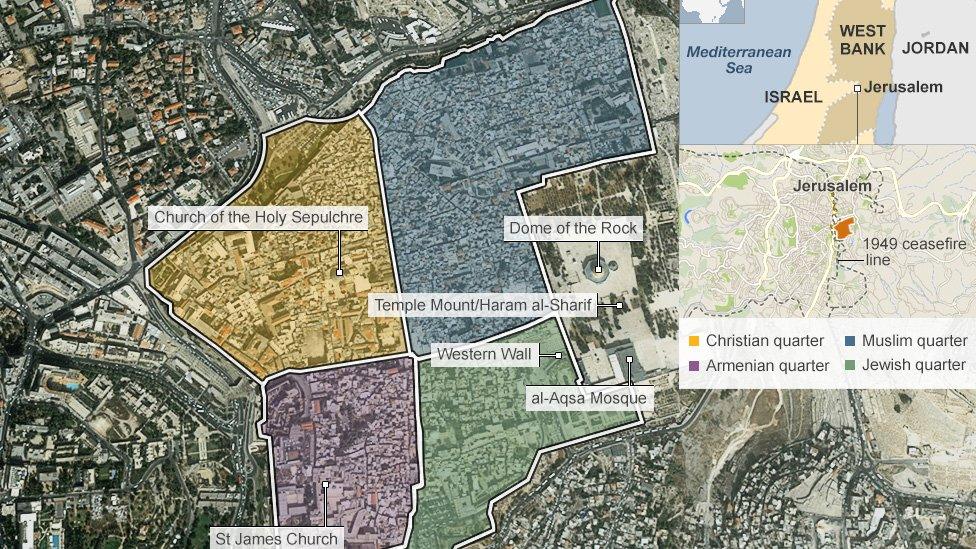

Why the ancient city of Jerusalem is so important

It also included evangelicals whose voice was amplified by the devout Christian in the White House, Vice-President Mike Pence.

"God decided Jerusalem was the capital of Israel more than 3,000 years ago during the time of King David," I was told by Dallas evangelical pastor Robert Jeffress, who cited Biblical history. He and another leading voice in the pro-Israel part of the Christian world delivered prayers at the opening ceremony.

So what about the peace process?

"The United States remains fully committed to facilitating a lasting peace agreement," Mr Trump also said in his recorded message.

He has declared an interest in solving the "toughest deal of all" and, despite the outrage over Jerusalem, the White House is still intent on rolling out a detailed initiative of a settlement it thinks is achievable.

Its authors - Mr Trump's son-in-law Jared Kushner and his lawyer Jason Greenblatt - concluded that shaking up the status quo could help their efforts by giving the Palestinians a dose of reality, says former Mid-East negotiator Aaron David Miller.

They also thought the Palestinians would eventually rally and resume contact after their initial shock and anger, external, according to the New York Times. So far they have not.

And the Palestinian deaths in Gaza make that prospect even less likely.

Analysis: Breaking down what Mr Trump said and what it means for peace

The administration argues it is simply recognising the obvious in accepting Jerusalem as Israel's capital and that the city's final boundaries can still be determined in negotiations.

But confusingly, Mr Trump has also said he has taken the issue "off the table". And he has failed to say anything about Palestinian claims to East Jerusalem.

So whatever the intent, he appears to have sided with Israel on one of the most volatile issues in the peace process and prejudiced the final outcome of any talks.

Does this mean an explosion?

The Trump administration has also sided with Israel in its response to the deadly violence on the Gaza border.

The White House accused Gaza's Hamas leaders of "intentionally and cynically" provoking Israel in an attempt at "gruesome propaganda" but, unlike European countries, it did not call on the army to exercise restraint.

Hamas has been directing the weeks-long protest campaign by Palestinians frustrated with Israel's economic blockade of Gaza.

Analysts said it was a chance for the militant Islamist movement to shift the blame for its own poor performance in government.

The question now is whether the hundreds of casualties will trigger an uprising, or intifada, that spreads to the West Bank.

Gaza's deadliest day of violence in years

The Jerusalem decision itself did not do so and there are many reasons why the Gaza violence may not. That includes divisions in the Palestinian leadership and the high cost for Palestinians of a return to sustained conflict.

But it is a volatile situation fuelled by a sense of Palestinian hopelessness that could lead to further escalation.

Crossing a red line?

What seems more likely to me at the moment is a slower unravelling of the peace process framework which for the past 25 years has led to neither peace nor all-out war.

Despite spasms of conflict, it has maintained certain fundamentals.

The Israelis have not annexed the West Bank. The Palestinian Authority continues security co-operation, in effect helping Israel police its own people.

The framework is held up by an American mediator that is seen by many as somewhat credible, if not neutral.

Every previous US administration has been pro-Israel but made some effort to understand and respond to the Palestinian narrative, says Mr Miller.

This one is so "deeply ensconced" in the Israeli narrative it has crossed a red line, he says.

If so, it will be difficult for it to keep propping up the framework, with unpredictable results.

It is true that key Arab countries seem more willing to sanction a settlement less favourable to the Palestinians than before because they want Israel as an ally against Iran.

But Mr Trump's decision on Jerusalem, and Israel's heavy-handed approach in Gaza, reduces their room for manoeuvre.

- Published15 May 2018

- Published14 May 2018

- Published14 May 2018

- Published13 May 2018

- Published1 July 2021

- Published7 December 2017

- Published17 February 2017

- Published18 November 2019

- Published30 October 2014