Moon walking: Ex-Nasa astronauts describe lunar experience

- Published

Twelve astronauts, all of them American, have walked on the moon

The last US mission to the Moon, Apollo 17, blasted off shortly before midnight on 7 December 1972. Its crew spent three days on the lunar surface, collecting samples and conducting experiments.

While China has said it aims to land astronauts on the Moon by the 2030s, in the decades since the Apollo 17 mission no human has returned to walk on the Moon.

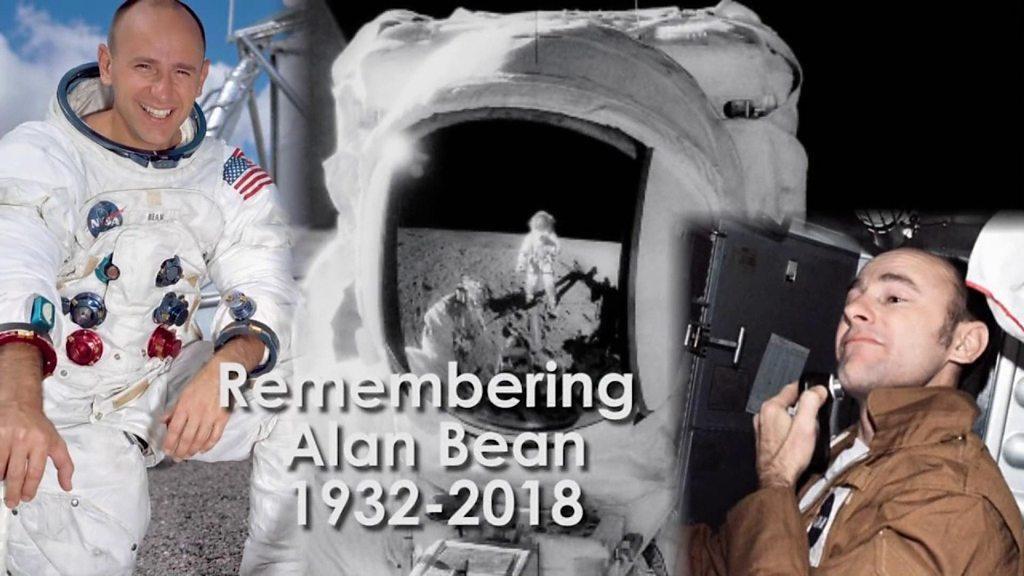

The death on Saturday of former US astronaut Alan Bean means there are now just four men alive who can describe what it is like to set foot on the Moon's surface. Here, through their writing and interviews, they recount their experiences.

Charles Duke: Born 3 October, 1935

Charles Duke is the youngest person to have walked on the moon

One of the most historically important voices in America, Charles Duke served as the spacecraft communicator - or CAPCOM - during the Apollo 11 mission when Neil Armstrong became the first person to walk on the Moon.

Born in North Carolina, an estimated 600 million television viewers heard his southern accent as the voice of Mission Control. "You got a bunch of guys about to turn blue. We're breathing again," he famously said after the landing was confirmed.

Within a few years he would be heading his own lunar mission.

"Would y'all like to go to the Moon with me?" he asked his children ahead of the Apollo 16 mission in 1972. As lunar module pilot, he would form part of an expedition tasked with inspecting and sampling a region in the Moon's rugged highlands.

When his children said they would very much like to come, Mr Duke promised to take a family portrait with him, external.

"I'd always planned to leave it [there]" he told Business Insider in 2015. "So when I dropped it, it was just to show the kids that I really did leave it on the Moon."

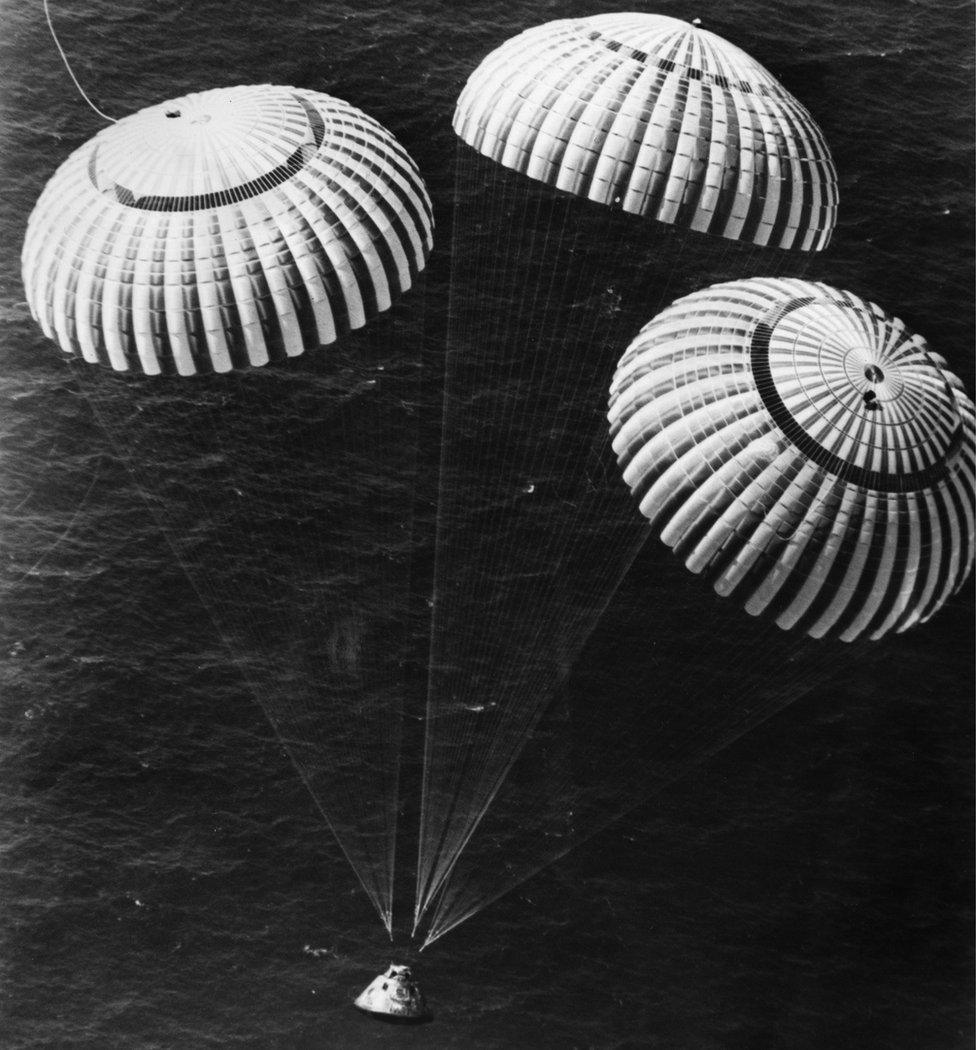

Charles Duke landed in the Pacific Ocean following the Apollo 16 mission on 16 May 1972

In 1999, Mr Duke spoke to Nasa about driving across the Moon's surface in a lunar rover, external. "I was taking pictures and describing the terrain we were going over," he said. "The car was amazing. It was electric, four-wheel drive, and it would climb a 25-degree slope."

"As far as the eye could see - was just the rolling terrain of lunar surface. It was really an impressive sight. My only regret of the whole mission was that we didn't take enough pictures with people in them."

David Scott: Born 6 June, 1932

David Scott said only an artist or poet could convey the true beauty of space

Born in San Antonio, Texas, David Scott graduated from the US Air Force before joining Nasa in 1963.

He flew in space three times and as commander of Apollo 15 was the seventh person to walk on the Moon, the first to drive on it, and the last American to fly solo in Earth's orbit.

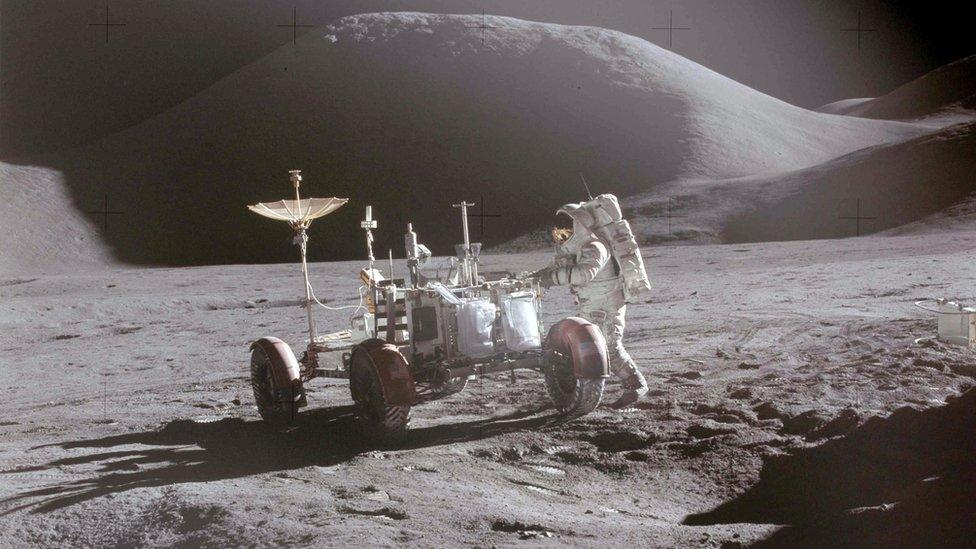

David Scott with the Lunar Roving Vehicle (LRV) during the Apollo 15 mission in 1971

"I remember… raising my hand towards the point where the Earth hung in the black sky above," he wrote in the book Two Sides of the Moon, external.

"By slowly raising my arm until my stiff, gloved thumb stood upright, I found my thumb could entirely blot our planet from view, One small gesture and the Earth was gone," he added.

Mr Scott says he is often asked about his time on the Moon and whether it changed him in any way.

"I describe the majesty of the lunar mountains," he says, "the layers of volcanic lava or the beauty of the sparkling crystals in the rocks".

He adds: "Only an artist or poet could convey the true beauty of space."

Harrison Schmitt: Born 3 July, 1935

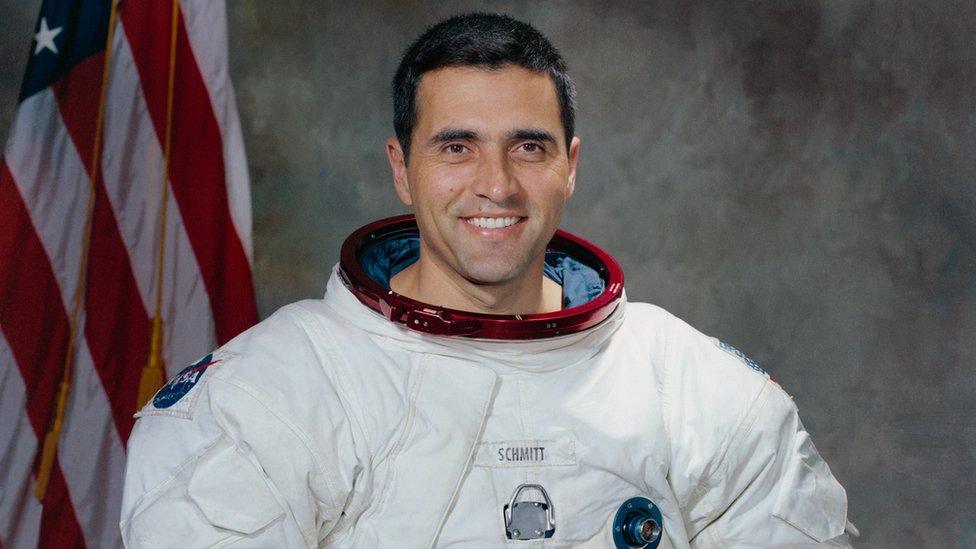

Harrison Schmitt is the last of the Apollo astronauts to "arrive and set foot" on the Moon

Born in Santa Rita, New Mexico, Harrison Schmitt had a different background to his peers.

A geologist and academic, he did not serve in the Air Force, but instead served as an astrogeologist, initially instructing Nasa astronauts during their geological field trips before becoming a Nasa scientist-astronaut in 1965.

He was assigned in August 1971 to fly on the last mission, Apollo 17, replacing Joe Engle as Lunar Module Pilot. Mr Schmitt landed on the Moon with commander Gene Cernan in December 1972.

The crew took the famous "Blue Marble" photograph which has become one of the most reproduced and recognisable photographs in history.

In a Nasa interview in 2000, Mr Schmitt said the light cast on the Moon provided impressive detail.

He said: "You could see features very clearly.

"I had a chance to see this magnificent valley that we were in, a valley deeper than the Grand Canyon, external... 6-7,000 ft mountains on either side, 35 miles long, and about four miles wide where we had landed."

Mr Schmitt said that one of the hardest things to get used to was the blackness of space.

"The biggest problem I think photographers have in printing pictures from space is actually finding a way to print black, absolute black. Certainly slides that you show will have a little bit of blue in the background, and you're just never going to get the contrast that we had visually on the Moon, because the sky was black."

Edwin 'Buzz' Aldrin: Born 20 January, 1930

Buzz Aldrin says the day will come when people will walk on Mars

Born in New Jersey, Buzz Aldrin became a Nasa astronaut in 1963 and was part of the Apollo 11 mission in 1969, which was the first space trip to send astronauts to the Moon.

During the mission he was accompanied by Neil Armstrong, who took the first steps on the Moon, only to be followed minutes later by Mr Aldrin himself. The two spent a total of 21 hours and 36 minutes on the Moon's surface.

Their spacecraft, the Eagle lunar module, landed in an area of the Moon called the Sea of Tranquillity, where they set about exploring the surface.

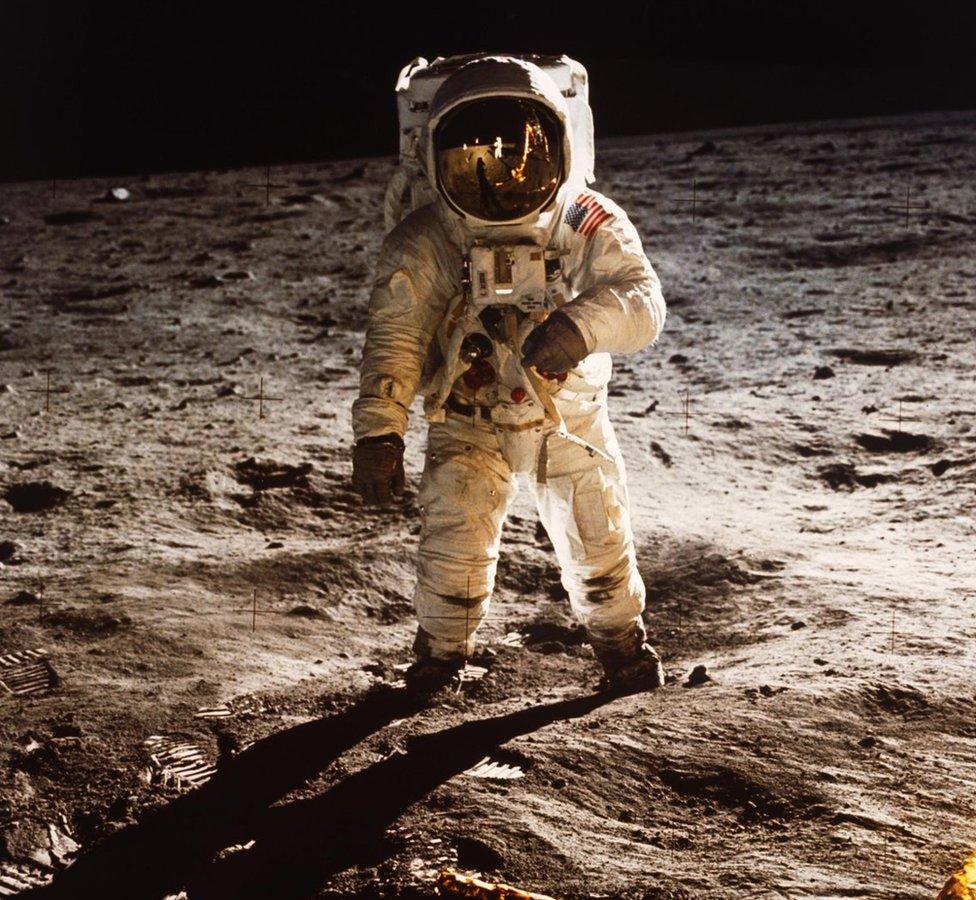

Photographs taken by Mr Armstrong of Mr Aldrin climbing down from the Eagle, which he piloted, and walking on the lunar surface are famous around the world.

In 1998, Mr Aldrin described the Moon's surface as being covered in a fine dark grey "talcum powder-like dust", external with a variety of scattered pebbles, rocks, and boulders.

"If you examine it under a microscope, you can see it's made up of tiny, solidified droplets of vaporised rock resulting from extreme velocity impacts," he said in an interview published by Scholastic.

He said that his term "magnificent desolation" referred in part to the achievement of being there, and in part to the "eons of lifelessness".

Mr Aldrin also described weightlessness as "one of the most fun and enjoyable, challenging and rewarding, experiences of spaceflight".

"Perhaps not too far from a trampoline, but without the springiness and instability," he said.

Since his trip to the Moon, Mr Aldrin has repeatedly suggested: "One day, we are going to send some people to the surface of Mars."

Buzz Aldrin launched a virtual reality movie in 2017 depicting life on Mars

- Published27 May 2018

- Published17 January 2017