Obituary: Henry Butler, the blind pianist and photographer

- Published

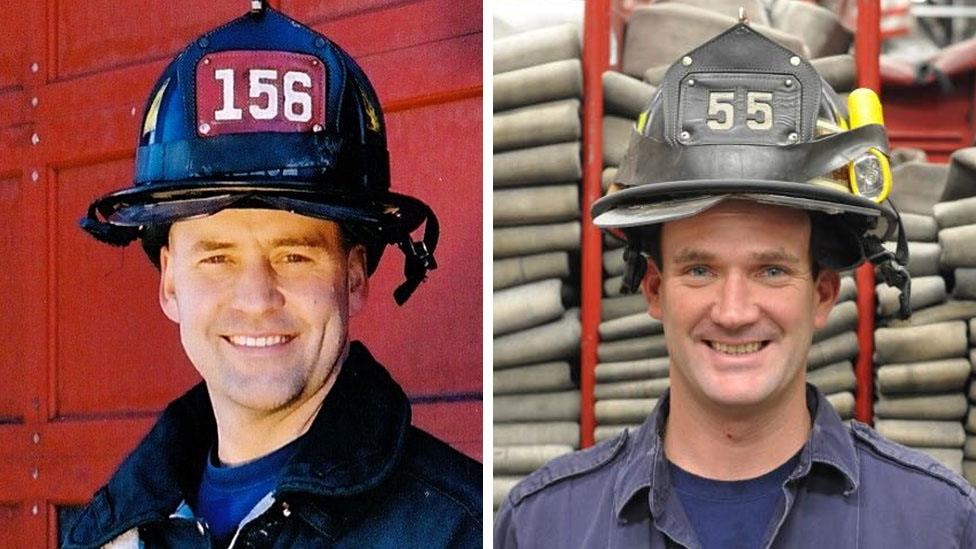

Butler performing with The Jambalaya Band in New Orleans in April

Four months after Hurricane Katrina destroyed his house in August 2005, Henry Butler returned home to New Orleans for the first time.

He couldn't see the damage - he had been blind since suffering glaucoma as a child. But he knew how bad it was. The stench that stuck to everything told him all he needed to know.

His sense of touch confirmed it. His beloved Mason & Hamlin piano, that dated from 1925, was covered in slime; the 8ft (2.4m) of water that had flooded the house had moved the piano some distance.

"When I touched the piano all the black keys were loose," Butler told The Trentonian three years after Katrina in 2008, external. "You could gather them up and hold them all in your hand. Even when I tried to mash down on the keys to get it to play something, all you would just hear is 'chump, chump'.

"It was not something I wanted to deal with at the time. There was no tone. There was nothing there, man."

The piano was not the only thing that had been lost: all the master tapes of Butler's recordings were gone, as were the thousands of pages of jazz theory, history and scores he had written in Braille.

Butler never did return to live in the city that had shaped his life and music, and he remained a "New Orleaner" in exile (a title he would give to one of his later songs).

He died of cancer in New York on 2 July, aged 69.

Butler was born in New Orleans in September 1948 and grew up in the Calliope housing projects that went on to be demolished after Katrina.

His first taste of music, he said in an interview in May this year, came aged four as he walked by neighbours' houses and heard them playing the piano.

New Orleans' musical heritage infused his entire childhood - from the ragtime piano of pioneering band leader Jelly Roll Morton he would hear coming from inside bars, to the Caribbean-tinged blues piano of his mentor Professor Longhair.

His enthusiasm for music became a passion aged 11 or 12 when his mother returned home one day with a record picked up in a bargain bin.

It was Viper's Drag by Fats Waller, a three-minute piano composition in the slide style Waller made famous, in which the left hand plays a low bass while the right plays an occasionally frantic melody.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Butler admired how it jumped from style to style with short transitions: it felt different, fresh, he said in an interview, external with the Library of Congress in 2010, before demonstrating on the piano what he had so admired about the composition.

From then on, Butler would listen to everything his mother brought home from the bargain bin, including pianist Duke Ellington and trombonist and bandleader Ray Conniff.

Butler did not have a piano at home, so would commit all these songs to memory by playing them over and over. Wherever he could find a piano, often at a neighbour's home, he would practise.

From 14, he was playing semi-professionally and developing his own style, one that combined classical training he had received with his enthusiasm for jazz, blues and calypso picked up in New Orleans.

Over his 11 albums, he could channel the influences of Schubert and then Caribbean music - sometimes seconds after each other. But he also performed alongside popular performers like Cyndi Lauper and the Afghan Whigs.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

On announcing his death in a statement on Butler's Facebook page, his management team paid tribute to "those extraordinary, lightning-cracking fingers blurring across the keyboard, the way he plucked and shifted and slipped the notes into places they had not yet inhabited so they could create a sort of new world order".

"Henry was grateful for every moment, every experience, every person he encountered until his last slow, smooth breath," a statement by his management team said.

More lives in profile

Butler did move away from New Orleans on occasions, including during a stint as a music teacher at an Illinois university. But Katrina severed most of the ties with his home city.

As the storm approached the Louisiana coast, Butler reacted as he had during previous storms - he left the city, but expected to return once the worst had passed. He took only a few items of clothes.

When Katrina made landfall as a Category Three storm, it pushed a huge storm surge along Louisiana's coast. Gentilly, the middle-class neighbourhood where Butler lived, was flooded from two directions when levees and canals overflowed. Across Louisiana, more than 1,500 people were killed.

Gentilly was one of the worst-hit areas of New Orleans

Butler watched the devastation from Farmerville, a small town in northern Louisiana. He understood quickly that everything had changed.

"Most people across the country just don't understand what happened," he said in 2010. "All of a sudden, the cultural footprint of the country is smaller. A lot of those people who were creating that culture couldn't get back - they were rich musically, but poor economically."

Between 2000 and 2015, rent in New Orleans increased by 50%, external even though the population fell by a third, due largely to Katrina. Musicians in the city are among its lowest earners, with an average annual salary of only $10,000 (£7,560).

One fundraising group, external has been able to replace the instruments of 3,000 musicians whose livelihoods were destroyed by Katrina, but many of the city's most noted artists left, and remain in exile.

Butler first moved to a hotel in Colorado, and said he struggled to cope with post-traumatic stress after losing his life's work.

"Like most people, I had it," he said a year after Katrina., external "I had it pretty seriously. And if I was going to do some crying, I wanted to do it in a place where nobody could see it."

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

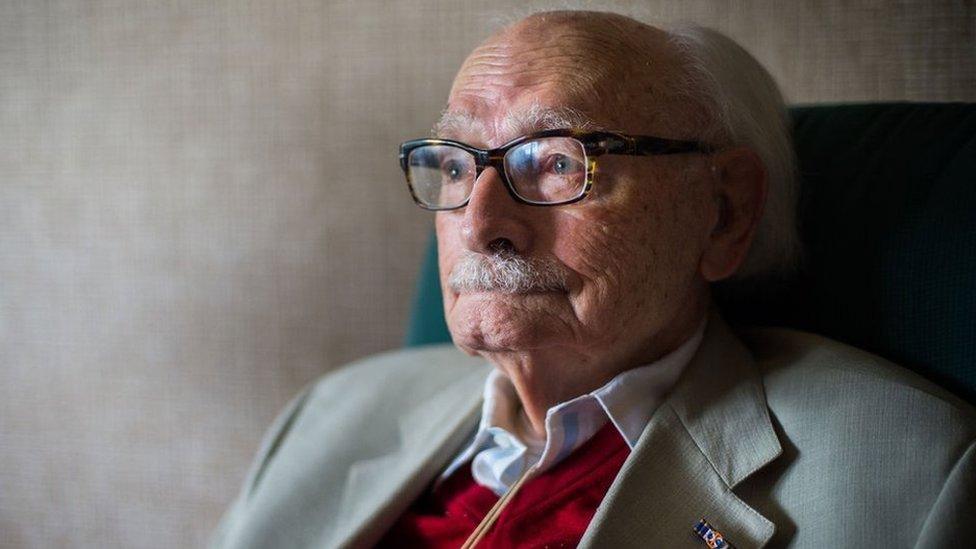

From Colorado, he moved to New York, where he continued to perform with several bands, and continued his passion for photography.

He would rely on friends to describe what was in the frame in front of him, and listen to the subject's voice so he could get a sense of how tall they were.

"I started because I wanted to become a participant in the visual arts field, and affect the consciousness of sighted people," he wrote in 2005., external "After going to exhibits, hearing people describe photos and paintings, I felt kind of empty - I wasn't getting all that I could get.

"The best thing, I decided, was to try to become at least an artist who was doing something in one of the visual arts."

Allow Facebook content?

This article contains content provided by Facebook. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Facebook cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Butler was diagnosed with stage-four colon cancer at the end of last year but continued to perform, including at April's New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival. It was his last show in his hometown.

"New Orleans is always going to be special to me," he said before the concert. "When you're born in a town, you always have that magnetic attraction to that place."

He leaves a brother, George, and a long-time partner, Annaliese Jakimides.

- Published24 June 2018

- Published26 May 2018

- Published30 March 2018

- Published18 March 2018

- Published25 March 2018