Mid-term election results: What it all means for Trump

- Published

The story of election night in two minutes

The Democrats have clawed their way back to a measure of power in the US federal government. The era of unified rule for Donald Trump and the Republicans is over.

Calling just two years an "era" may be a stretch, of course, but in the age of Trump even days and weeks can seem like an infinite and expanding series of news cycles.

For the duration of his presidency, Mr Trump has benefited from a friendly Congress - generally supportive of his words and deeds, accommodating of his policy priorities and deferential when it comes to oversight.

In two months, when the new Democratic-controlled House arrives in Washington, all that will change.

The House of Representatives, which reliably churned out hard-line immigration legislation, Obamacare repeal and steep cuts to social programmes under Republican rule - even though many of the bills died in the Senate - will now start offering up progressive priorities.

First on the list, according to the likely Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, is a package of government ethics and election reform measures.

Now it's Democrats' turn to see their efforts languish in the Senate, but liberals finally have a platform to showcase what they would do with full control of Congress - and, perhaps, the presidency in 2020.

Meanwhile, Mr Trump's only hope of achieving any signature laws is by working across the aisle - which may be a heavy lift for a man who spent the past few months disparaging his political opponents in the starkest of language at rallies across the country.

What losing the House means for Donald Trump's presidency.

Of more immediate concern for the president, however, is that Democrats now have some teeth behind their efforts to scrutinise his administration.

The House Intelligence Committee, which ran the chamber's investigation into 2016 Russian investigation meddling, will be under the control of outspoken Trump antagonist Adam Schiff, who has pledged to look deeper into the president's foreign financial dealings.

It may not be long before the president's tax returns, that Holy Grail for some of the president's liberal antagonists, are revealed to the public.

Other members of the Trump administration may also be open to scrutiny. Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke may be first under the spotlight following accusations that he took official actions that benefited his business interests.

Then there's the i-word - impeachment.

It takes a simple majority of the House to undertake the first step to removing a president, and the Democrats now have that majority.

Up until now, members of the Democratic congressional leadership have been downplaying the prospect of starting that particular ball rolling. If Special Counsel Robert Mueller files his report into possible collusion between Russia and the Trump 2016 presidential campaign in the coming days (weeks or months) and it contains damning information, that calculus could quickly change.

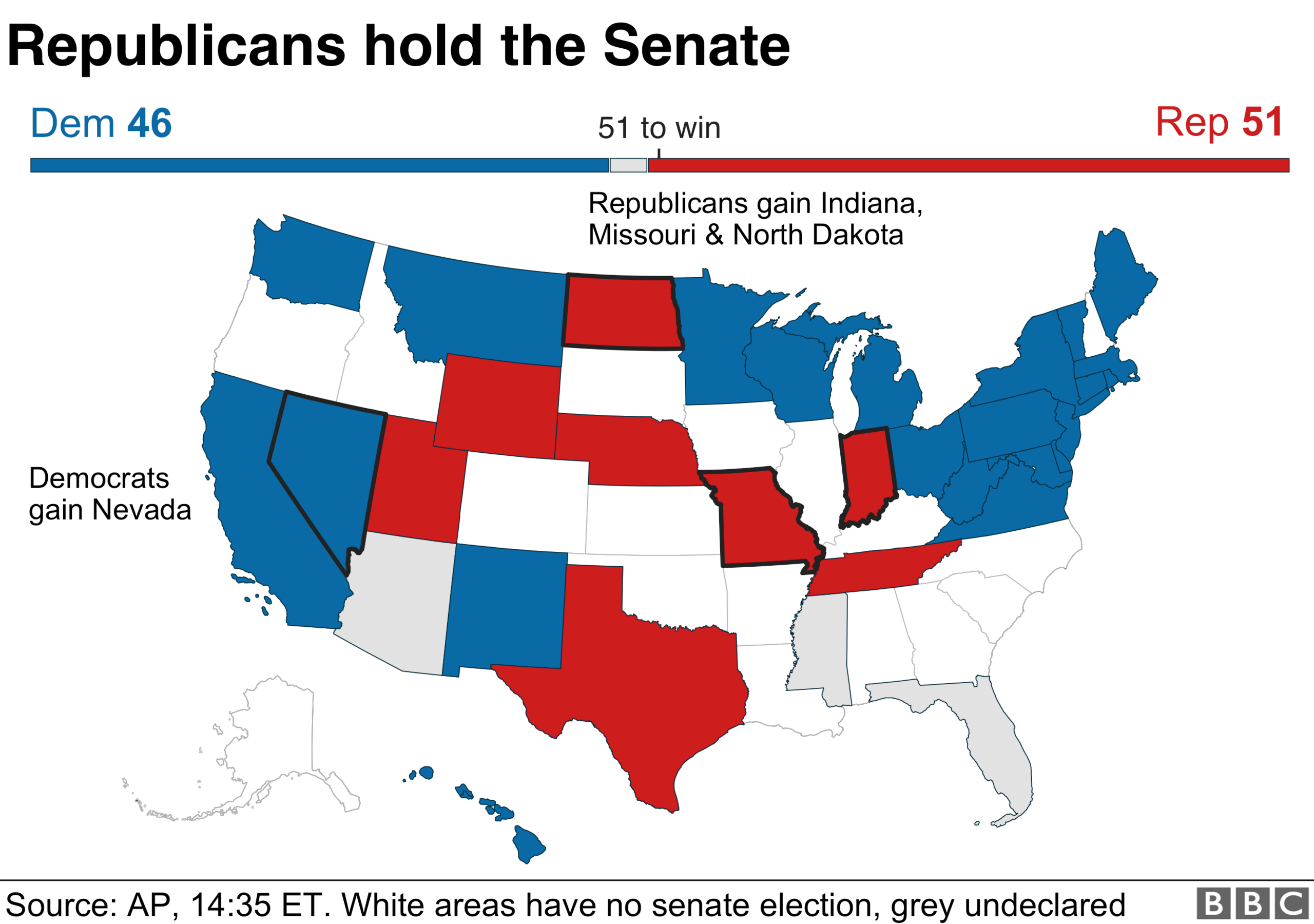

Although the president may be in for a rude awakening from House Democrats, the Republicans' ability to hold - and expand - their majority in the Senate is unequivocally good news for Mr Trump.

Democrats had moments to cheer

The Republican Party's conservative pipeline to the federal judiciary remains open. The president has already appointed 84 judges to the courts, including two Supreme Court justices. Democrats are left hoping that the four liberal members of the bench remain in good health for the next two years.

It will now also be less difficult for the Senate to confirm new high-level Trump administration officials who might have been blocked or significantly delayed if Democrats had taken over.

This makes it easier, say, for the president to fire and replace "beleaguered" Attorney General Jeff Sessions with someone who would curtail Mr Mueller's Russia probe.

At some point the president may even decide to nominate a new director of the Environmental Protection Agency, a position that has been filled on an interim basis since Scott Pruitt resigned under an ethical cloud on 6 July.

Beyond the nuts-and-bolts reality of partisan control of Congress, the mid-terms have larger implications for Mr Trump's political power - and his prospects for re-election.

For two years he's governed the nation with an eye toward satisfying his loyal base both with policy and rhetoric - on trade, immigration, government regulation and foreign policy. Unlike his predecessors, he's made little effort to broaden his national appeal.

That probably helped his party win some Senate seats in states where the president remains popular, but the verdict was far from universal. Joe Manchin once again defied political gravity in West Virginia, and contests in Wisconsin, Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania that may have seemed in reach in the days after the president's 2016 victory were comfortable wins for the Democratic incumbents.

Meanwhile, the preach-to-the-choir strategy may have proven costly in suburban, traditionally Republican congressional districts with wealthier, better-educated populations. These voters stuck by Mr Trump in 2016, but they deserted his party in droves this year.

If that trend continues, states like Arizona, Pennsylvania and Michigan may prove more difficult for the president to carry in a 2020 re-election campaign. Mr Trump has liked to boast about all the House Republicans who won special elections during his administration, but this time around, as voters headed to the polls across the nation, his political losses had a sizeable body count.

If Mr Trump is eying his re-election prospects - and, let's be honest, that's what every first-term president does pretty much from inauguration day on - Tuesday's results have some bright spots, however.

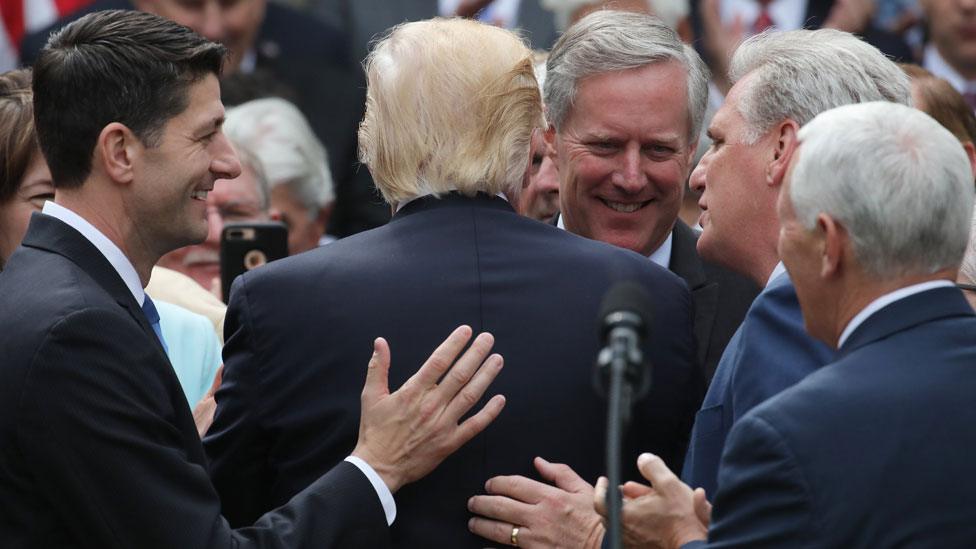

Gone are the days of allies leading the House

A Trump-adoring Republican, Ron DeSantis, won the governor's mansion in Florida, as did Republicans in Iowa and Ohio. If Mr Trump's party can win state-wide in those battleground states in the current political climate, there's no reason to think they can't swing the president's way again in two years.

Even handing over power to Democrats in the House of Representatives may have a bit of a silver lining for the president. Now he'll have someone to blame if the economy takes a turn for the worse (and, given business cycle realities, it might). He's got a ready-made explanation for why he can't get anything done in the next two years - and a pitch for what needs to change in the next election.

Day in and day out, he'll have a set of clear political opponents to contrast himself with.

Both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama lost control of the House in their first term in office and went on to win re-election. History, serving as a guide, predicted this would probably be a bad night for the president.

History also indicates that while the road may be rocky, better days could be ahead.