Has Trump turned his back on Europe?

- Published

Donald Trump (R) has clashed with European leaders including French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel

As the EU says the US government has effectively downgraded its diplomatic status in Washington, how has the transatlantic relationship changed under Donald Trump's presidency?

For generations, American presidents have saved some of their warmest words for their European colleagues.

They came to the Berlin Wall and spoke of freedom - and, after it fell, they spoke of a new era of co-operation with a rebuilt Europe. But in the era of Donald Trump, leaders across the continent now know that those days have gone.

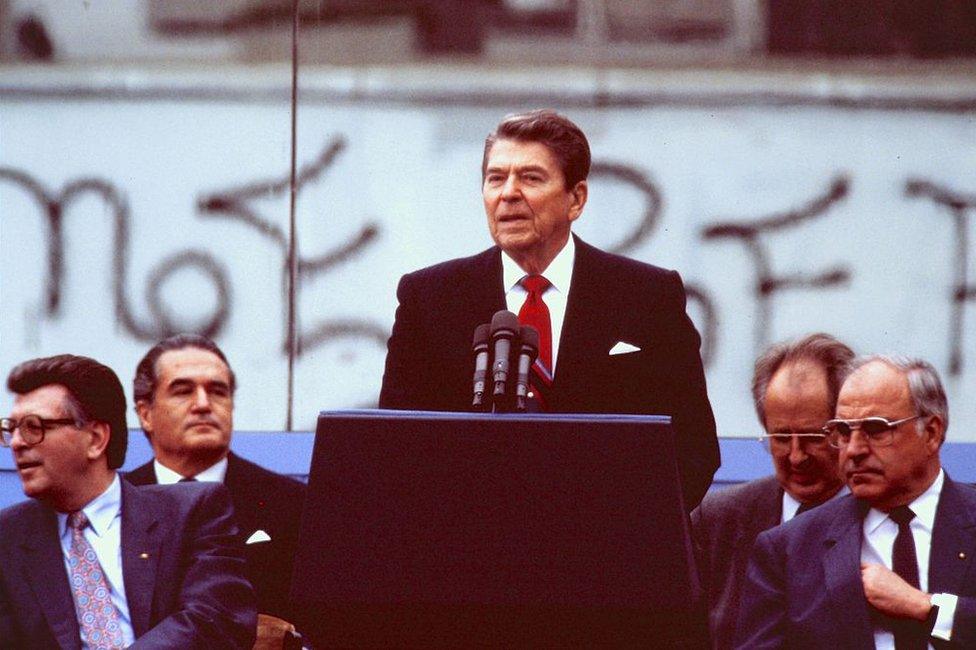

John F Kennedy's "Ich bin ein Berliner," declaration, Ronald Reagan's 1987 message to Moscow: "Mr Gorbachev tear down this wall," George HW Bush's promises of collaboration after the Cold War and Barack Obama's warm words about binding ties across the Atlantic are all now distant memories.

With every visit to Europe and every White House tweet about the cost of Nato or EU tariffs, this president makes it clear that he believes Europe is more often an impediment than an ally.

None of his predecessors would have dreamed of calling the EU a "foe", as President Trump did in a recent interview about trade.

With Europe embroiled in its Brexit difficulties, which leave so many questions unanswered, its leaders also find themselves scrambling to work out what it might mean if these old ties with the United States continue to unravel.

That was what German Chancellor Angela Merkel was contemplating when she said, a few months ago, that it was time for Europe to take its destiny into its own hands.

It was instructive to spend a few days in Berlin recently and to hear over and over again a version of these words.

As Daniela Schwarzer, from the German Council on Foreign Relations think tank, put it: "The United States, with its 'America first' approach, has put Europe and Germany into the space of a strategic competitor, if not even an enemy."

Many of the journalists who watched Donald Trump's inaugural presidential address two years ago - in which the "America first" phrase became the theme of a nationalist marching song - wondered how far he would go. Wouldn't the realities of power kick in? It seems not.

Karen Donfried, who served as President Obama's European adviser, told me: "I would not assume that whoever follows Donald Trump goes back to where we were pre-Trump, because you can't.

"Those four or eight years that Donald Trump is president will have changed the relationship and changed the US role in the world, so it will be different."

How different? Think of a rolling crisis on Europe's eastern border - between Ukraine and Russia.

Since the contentious annexation of Crimea in 2014 - which the Obama administration declared illegal and a reason for sanctions on Russia - there has been a series of clashes that have made it clear Vladimir Putin is not interested in taking the pressure off.

Why Ukraine-Russia sea clash is fraught with risk

That is likely to be obvious in the run-up to the Ukrainian presidential election in March.

But, in Washington, Donald Trump has shown little interest in the concern across Europe - especially in Poland and Germany - about President Putin's expansionist policy.

Instead of promoting a collective approach, he has preferred his characteristic man-to-man style of negotiating, claiming that he rescued his relationship with President Putin in one conversation, a two-hour closed summit in Helsinki in July 2018.

Trump-Putin summit: After Helsinki, the fallout at home

But in Angela Merkel's office, there was incredulity that the White House didn't consult its allies before that meeting with the Russian president and that it passed on almost nothing afterwards, beyond what emerged via Twitter.

Find out more:

James Naughtie presents America's Friends on BBC Radio 4 on Monday, 14 January, at 20:00 GMT and Wednesday, 16 January, at 11:00 GMT.

Or you can listen again after broadcast via the BBC Radio 4 website or BBC Sounds.

"The Americans are our most important ally and we know how much we depend on the American contribution to our defence and security in the EU," said David McAllister, German-born to a Scots father, an MEP for Angela Merkel's CDU party, and one of her closest colleagues.

"But it's now about strengthening the European pillar within Nato, because under this president - and perhaps also under the next president - we might see less appetite in Washington to get involved in our immediate neighbourhood if it might be necessary."

So, rethinking is needed inside Nato. But that challenge is coming at an awkward moment: Angela Merkel is stepping down in two years, meaning Europe's dominant political figure will be gone.

In Berlin, I also spoke to retired American diplomat John Kornblum, who followed the course of the Cold War from the 1960s to the end, and then became the US's German ambassador.

Ronald Reagan's call to Mikhail Gorbachev to tear down the Berlin Wall in June 1987 was one of the most significant acts of his presidency

He wrote much of that 1987 Reagan speech, delivered at a time when Western objectives were much clearer than they are today.

"Europe is at a crossroads," he told me. "It's now almost 30 years since the end of the Cold War. Europe is in a much weaker, less independent, less stable condition today than it was 30 years ago. And that's an unfortunate thing to say but it's true."

And the solution? It's easier to ask the questions than to find the answers. That's the tenor of these times.

What everyone does now know is that Europe and the United States, however much they retain their shared values, have to re-engineer their relationship as together they negotiate a new age of uncertainty.

- Published8 January 2019

- Published26 July 2018

- Published11 July 2018

- Published11 July 2018

- Published16 May 2018