Drop-off baby boxes: Can they help save lives in the US?

- Published

The box on the side of the Indiana fire station resembles some sort of postal hatch. Pull open the external door and there is space enough for a medium-sized parcel.

But this isn't a place to store your deliveries; it is designed for newborn babies.

Installed in December, it is the seventh "baby box" in the state, and it is targeted at mothers in desperate need.

More complex than they first appear, the boxes are fitted with temperature regulators and sensors. When a baby is placed inside, a silent alarm goes off, alerting the emergency services and allowing the child to be retrieved in a target time of less than five minutes.

"They are a last resort," insists Priscilla Pruitt, who works for Safe Haven Baby Boxes, a campaigning organisation that has been pushing for their introduction across the country. The group says the boxes are needed to combat infanticide, when mothers - often young and fearful - give birth alone and are unable to cope.

"Abandonment is a problem," she says. "These young women don't want to be known or seen. Especially in small towns where everyone knows everyone."

Yet not everyone thinks they are a good idea.

Fathers' rights groups object, saying they allow only one parent to make the decision. And the UN has opposed their use in other parts of the world, calling for countries to offer more family planning and other support to address the root causes of abandonments, such as poverty, instead.

Are these boxes new?

In the US, this crop of baby boxes first started appearing in 2016, but the concept is ancient.

Dating back to medieval times, they were originally known as foundling wheels - cylindrical barrels on the side of hospitals, churches or orphanages.

Within the last 20 years, they have undergone a small-scale revival, and can be found in various countries, including Pakistan, Malaysia, Germany and Switzerland.

Warsaw in Poland also has baby boxes

They are often provided by charities. Safe Haven Baby Boxes - an non-profit organisation - says it has almost two dozen more lined up and has raised funding for 100. The money is largely coming from Knights of Columbus, a Catholic men's organisation.

Which US states have baby boxes?

Legislation must be passed for the boxes to be permitted in individual states.

This has already gone through in Indiana, where there are seven boxes; Ohio, where there are two; and Pennsylvania, where the first one is expected soon.

A bill is in progress in New Jersey, but has yet to pass. A campaign is under way in Georgia.

In December, Michigan's senate passed the bill, but it was vetoed shortly afterwards by the state governor.

Governor Rick Snyder wrote a letter, external saying that the state's existing safe haven law - which allows babies to be left with authorities anonymously - was sufficient.

"I do not believe it is appropriate to allow for parents to surrender a baby by simply depositing the baby into a device rather than physically handing the baby to a uniformed police, fire or hospital employee," he said.

What is a safe haven law?

Abandoning a baby is illegal in the US. However, the safe haven law decriminalises the act, if the baby is passed into safe hands - typically only in the first couple of days of its life.

Texas was the first place to pass the law in 1999, and all the 49 other states followed.

Texas Department of Family and Protective Services says it has seen 131 babies handed over under the safe haven law since its records began in 2004.

Such figures are hard to analyse, according to experts. It is impossible to determine what the babies' fate might have been otherwise - some may have died, some may have been adopted, some may have been kept.

Do baby boxes save lives?

Denmark's national welfare research centre, Vive, has been researching their effectiveness in Europe, after Danish politicians signalled interest in offering them.

"In Germany, where they have had baby hatches since 2000, a fall in the number of abandoned babies found dead outdoors has not been registered," said Marie Jakobsen, the chief analyst at Vive, according to The Copenhagen Post., external

Safe Haven Baby Boxes says their proof comes from their usage. Their baby boxes have been used three times since April 2016. The organisation says that those three may not have survived otherwise.

A South Korean film about pastor and baby box advocate Lee Jong-rak boosted support for the concept

"It is hard to say this [baby boxes] is a bad idea, but it seems slightly misguided," says Michelle Oberman, a law professor at California's Santa Clara University School of Law, and an expert on legal and ethical issues surrounding adolescence, pregnancy and motherhood.

"The safe haven law is the least worst option when the alternative is a baby in a dumpster, but there are reasons why we have set up adoption programmes so we have as much information as possible."

The main problem, she says, is these initiatives are unlikely to be reaching their targets. The pregnant women who suddenly find themselves giving birth alone are often very young teenagers who have been denying or concealing their pregnancies out of fear and shame.

"I find it hard to imagine that immediately after delivering baby, by herself in bathroom, she is expected to know the law, and get on a bus and into an Uber and drop it off," says Ms Oberman.

Safe Haven Baby Boxes says its team is working with schools and youth groups to spread awareness.

The organisation also runs a 24-hour hotline to counsel women. "We try to help women do anything apart from dumping their baby. The last thing we talk to them about is the baby box," says Mrs Pruitt. It also has a system allowing women to get in touch to provide more information.

The organisation's founder, Monica Kelsey, was herself abandoned as a baby, after her mother was raped aged 17. She says this is her motivation for the baby box scheme and her work as an anti-abortion speaker.

How big a problem is neonaticide in the US?

"The type of young woman this affects is typically emotionally isolated and very passive, with no-one they can trust," explains Ms Oberman. "They think maybe this will go away. Maybe I am not pregnant. Maybe I am imagining it." Then, they are shocked to give birth, they have no plan, and sometimes just want to get rid of the baby to pretend it never happened.

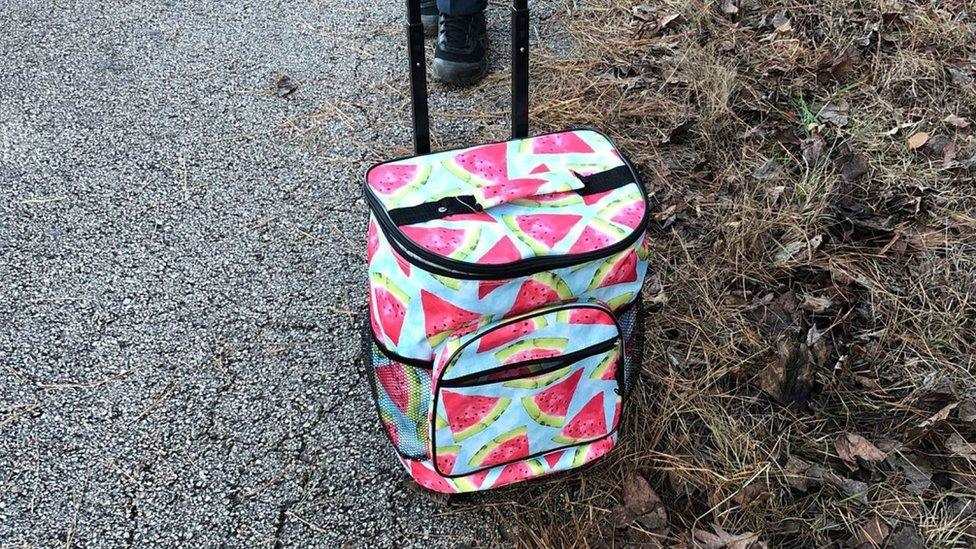

Police in Georgia found a baby's body inside this cool bag in January

The figures on neonaticide - the act of a parent murdering their own child during the first hours of its life - are hard to pin down.

"It is vastly underestimated," says Cheryl Meyer, an associate dean of the Wright State School of Professional Psychology in Ohio who co-authored a book on the subject alongside Ms Oberman.

"It is impossible to determine as many go undetected or they are juvenile offenders. Often the cases never reach the media. States also may also record the crime as homicide rather than neonaticide," she adds.

How does this play into wider issues?

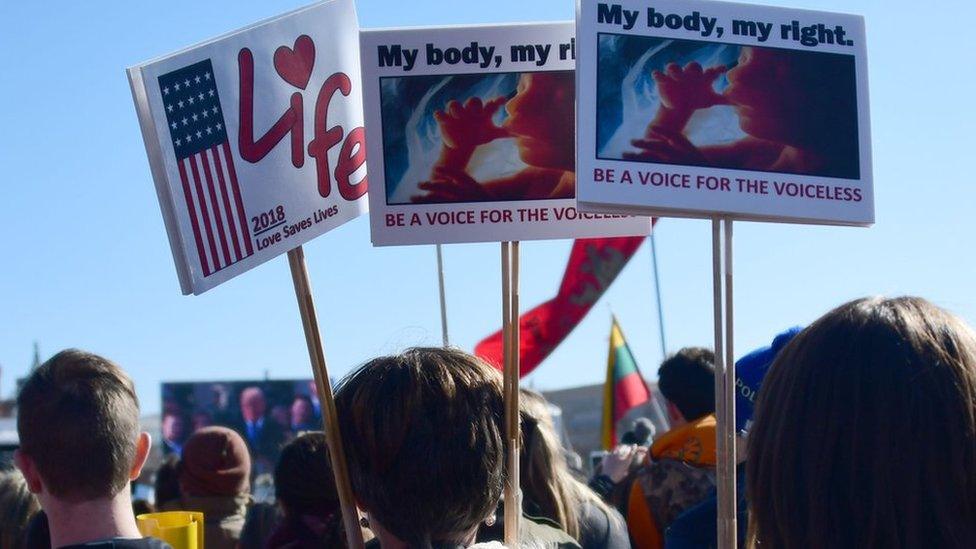

Indiana - where these baby boxes began - is home state of Vice-President Mike Pence, who is strongly anti-abortion and passed some of the country's strictest abortion laws when he was state governor.

"Safe haven laws and boxes. All of this is tied into how abortion is perceived, personal beliefs, religion," says Ms Meyer.

When interviewing women in prison for neonaticide, Ms Meyers said she asked them why they didn't have an abortion, and many said it was because they didn't believe in it.

"There is a sad irony there," she adds.

Shelly Dodson, director of the All Options drop-in pregnancy resource centre in Bloomington, Indiana, says a lot of similar centres have religious links or a pro-life bias. The centre she runs, which opened in 2015, deliberately doesn't.

"Pro-life, pro-choice - it is always presented as a dichotomy here, but a lot of people feel left out of those two options," she says. "The reality is complex and messy. I think a lot of us here have shared compassion underneath it all."

Meanwhile, Ms Kelsey is adamant that the baby boxes should not be seen as controversial. "This is about saving lives," she says.

- Published18 May 2018

- Published2 May 2018