The butterflies that could stop Trump’s wall

- Published

The obstacles to President Donald Trump's border wall are not confined to the four walls of Congress. As areas are cleared to start building new sections, some landowners, including a butterfly sanctuary, have sued to stop the construction.

Marianna Trevino Wright sits on a bench near a wooded section of the National Butterfly Center and begins identifying animals.

Scissortail flycatchers, green jays, olive sparrows and clay-coloured thrushes swoop by, pecking at oranges set out as a snack and splashing in a bubbling fountain. From the tree branches above, great-tailed grackles screech and whistle like avian car alarms.

Closer to the earth, a menagerie of butterflies flit among the nearby flowering bushes. Zebra Heliconians and large orange sulfurs; queens and red-bordered pixies.

Then there are the other sights and sounds at the centre.

The hum of a US Department of Homeland Security helicopter high overhead. Border Patrol agents buzzing by on motorcycles and ATVs, their faces obscured by masks and goggles, pistols at their side.

The rumble of trucks dragging tyres behind them, smoothing dusty roads so the footprints of interlopers can more easily be spotted.

A government powerboat, with menacing .30-calibre machine guns on its deck, roaring down the river.

Ms Wright says the environmental preserve has become a war zone

The butterfly centre, of which Wright is the director, sits on 110 acres near the southern tip of Texas - an area of low-lying marshes, brush and scrub forests, offering a variety of ecosystems that provide ample habitat for migratory species of all shapes and sizes.

It is also flush along the Rio Grande River, which forms more than 1,260 miles (2027 km) of the 2,000-mile border between the United States and Mexico.

That puts the small, private environmental preserve in the centre of a raging debate over immigration and national security - and whether and where to build Donald Trump's oft-promised border wall.

"It is a war zone," Wright says. "That's what the government wants it to appear to be. It's all theatre. So they've got to have all the actors, all the costumes and all the props."

South Texas is a funnel of all sorts for animals that winter in Mexico and burst into the northern climes as the weather warms.

It's also the closest point in the US geographically to Central America, where a growing number of families have been fleeing poverty and political violence to seek refuge on US soil.

Battle for the borderlands

Near where Wright was bird-spotting, a broad levee topped by a gravel road bisects the butterfly centre. This is where the US government wants to build a new section of wall, using its broad powers to confiscate private property for public use.

Wright points out that the Border Patrol has already built a massive gate along the road - made of the same kind of rust-coloured steel it uses elsewhere in its bollard fencing. For now the structure, unconnected to any other barriers, is more symbolic than useful. That may someday change.

Wright steps aside, as yet another Border Patrol truck rolls by. Its occupants, in green uniforms, smile and wave politely.

"They're only doing that because they know you're with the media," she explains.

Border Patrol has built part of a massive steel gate near the centre

Her relationship with the government personnel that have turned her little slice of Texas into a quasi-militarised zone is usually less than friendly, she says.

She explains how, on a summer's day in 2017, she discovered five private contractors with chainsaws and heavy equipment, clearing brush and trees along a road that runs the mile and a half from the levee to the banks of the Rio Grande.

They left after a brief confrontation, but a few weeks later a government representative arrived unannounced at her office.

"He came with posters of the border wall design and told me they were building the wall on our property," Wright says.

The plans laid out an 18-foot vertical slab of concrete along the front edge of the levee. An 18-foot-high steel bollard fence rises from there, with accompanying 22-foot-tall "all-night blitzkrieg lighting," as she calls it. The current two-lane road expands to the width of six lanes.

"And when the contractors return," she says the man added, "they would have a green-uniform [Border Patrol] presence. So armed federal agents on private property protecting for-profit contractors."

Wright worries about the impact the planned border wall would have on the species in her sanctuary.

Some birds and butterflies would be able to pass through or over the steel slates, but not all.

And terrestrial wildlife, like armadillos and endangered snakes and lizards, will be trapped behind the wall when the Rio Grande floods. In addition, natural habitat for all the various animals would be cleared as part of the wall's "enforcement zone".

After her meeting with the government agent, Wright began a multi-year series of court battles to block the US government from building its wall on the centre's private property.

It has made her a hero to environmentalists and immigration activists, and the target of obscenity-laden vitriol from some Trump supporters and wall proponents.

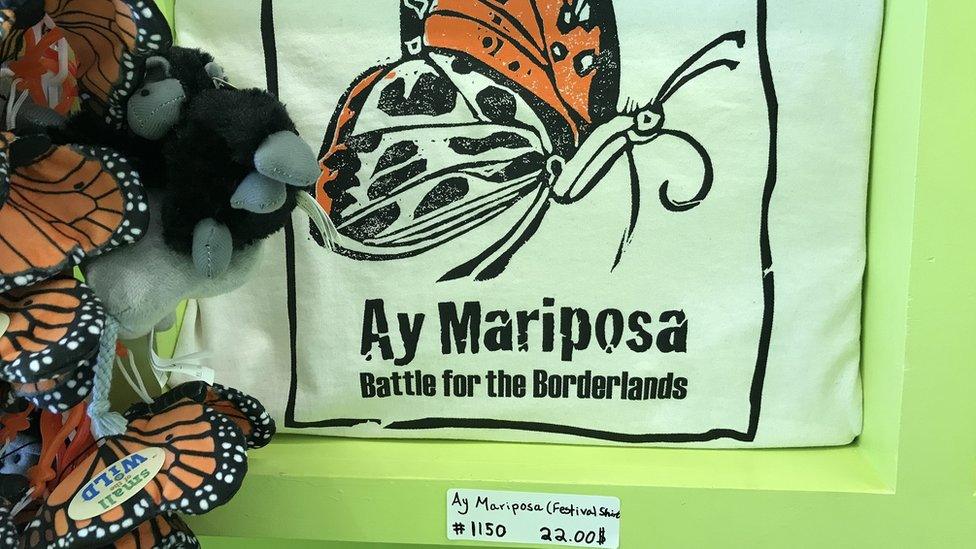

Added to the centre's gift shop collection of insect-related knick-knacks and books are displays explaining the ongoing legal battle and "Ay Mariposa" butterfly T-shirts, captioned "Battle for the Borderlands". More than $100,000 has been raised for the centre's legal fees.

"We're suing over the violation of the NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] and the Endangered Species Act and the de facto seizure of our private property, as well as multiple other egregious acts by Border Patrol," Wright says.

The centre filed intent-to-sue documents. Then the actual lawsuit. Then … nothing. No response from the federal government, and no court hearing for more than a year.

Finally, last month, as contractors moved heavy construction equipment onto the property, the centre filed a temporary restraining order.

The equipment was removed, but on 14 February, a federal judge in Washington dismissed the lawsuit.

The laundry list of environmental and cultural preservation laws that the centre's lawyers say the wall would violate had all been properly waived by the Department of Homeland Security, the judge wrote. Other possible violations could not be litigated until after the government breaks ground on the wall.

Wright and her legal team have appealed, while they wait for the government to make its next move.

More voices from the border:

In February, Congress appropriated $1.4bn for new wall construction. Lawmakers stipulated, however, that none of the money could be used for new fencing through the butterfly centre, wildlife preserves, a Catholic church and several other private properties that have gained prominence for opposing the construction.

Those restrictions do not apply to the money the Trump administration has freed up through the president's recent emergency declaration, however, prompting fears that the butterfly centre's reprieve may only be temporary.

Tim Beeken, one of the centre's lawyers, says they'll be ready if the builders return.

He contends Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen didn't properly consult with landowners before waiving the federal laws and regulations that normally apply to such large construction projects.

"What we want them to do is comply with those laws, move more deliberately and allow them to think about ways to protect the centre's property interests," Beeken says.

A group of migrants crosses into the US having rafted over the Rio Grande River in McAllen

Such a strategy has been used already with some success - 63 times, by the Washington Post's count, external - to block other Trump administration policies that were rolled out without jumping through the proper procedural hoops.

It's a technical argument, but if it works it would buy the centre some time.

A wall, but not a solution

Wright says that in her six years at the Butterfly Center, she's only personally witnessed three small groups of undocumented migrants coming through the property.

US government numbers, however, indicate that the lower Rio Grande Valley is becoming an increasingly popular entry point for the Central American families and unaccompanied children seeking asylum in the US.

From October to February, the Border Patrol apprehended 58,032 families on US soil - a 209% increase over the same time period a year earlier.

Although Donald Trump has been touting a wall as a way of ensuring border security since the early days of his presidential campaign, the spike in unauthorised crossings has given his call a new sense of urgency - one echoed by Republican politicians and their supporters.

"I absolutely think the border wall is necessary," says Joacim Hernandez, a businessman in nearby McAllen, Texas, and president of the area's Young Republicans.

"It is necessary in some areas to help control the flow of traffic and assist Border Patrol agents and their job of apprehending illegal immigrants."

McAllen Young Republicans President Joacim Hernandez says he believes a wall is necessary

He warns that if the wall goes up in most of the Rio Grande Valley but not in places like the butterfly centre, those exposed areas will become the preferred illegal entry-point - with the increased traffic leading to exactly the kind of massive environmental damage the centre's defenders hoped to avoid.

That may end up being the case, but there is one small complication. A wall - even one along the length of Rio Grande in southern Texas - won't solve the current immigration problem.

"Our wall is oftentimes a mile or more away from the river, the real border," says Jim Darling, mayor of McAllen. Build it any closer, and it would be in the river's flood plain.

As soon as migrants cross the river, he continues, they're eligible to have their political asylum claims heard by a US judge.

In other parts of the US - such as California - the government is building walls right on the border, keeping would-be immigrants from setting foot on US soil.

In the Rio Grande, however, the crossings won't end until US asylum law changes - and those who are fleeing their homes in Central America know that the law has changed, and getting on to dry land would not be enough.

The current system has prompted more would-be migrants to steer away from places like Tijuana, on the California border, and head toward Texas, even though the adjoining Mexican state of Tamaulipas struggles to deal with violence and the influence of drug cartels.

"The policy right now is, let's keep pounding for the wall and ignore this massive problem we're creating with asylum and the failure of immigration policy," says Darling.

A missing crisis

The World Birding Center in Hidalgo, Texas, offers a preview of what could be in store for the butterfly centre, just a dozen miles up the river.

The tree-dotted grounds still attract wildlife-watchers, with binoculars around their necks and animal-identification charts in hand. A canal links the Rio Grande to an old pumphouse, which once supplied water to the agricultural fields to the north.

The pumphouse used to be a symbol of the region's connection to, and dependence on, the waters of the Rio Grande.

Now, the river is only accessible through a narrow road at the far end of the canal. The rest of the property is lined with the kind of towering border wall Mr Trump promises to extend.

Border fence between El Paso and Juarez Chihuahua

The river levee is a solid vertical concrete embankment. A rusty-red bollard fence looms over areas where the concrete isn't as high. Chain-link fence and curled concertina wire with razor-sharp spines fill in where there's not steel.

A massive electronic gate near the pumphouse looks like something out of Jurassic Park, suitable for holding back an angry Tyrannosaurus.

Cameras dot the fence line, and at the other end, where the road curves down to the river, a mobile Border Patrol watchtower with dark, tinted windows surveils the area.

The wall is a tourist attraction of sorts, drawing some who may have come for a bird-watching stroll or a visit to the pumphouse museum.

Teresa Ruess, an Iowan who spends winters in balmy southern Texas with her husband, pauses at the imposing gate and says she approves of the wall.

"I hate to say it, but I think we need it," she says, adding that immigrants coming across the river could bring diseases into the US.

"But I feel for the kids," she continues.

Farther down the gravel road, a young couple - Ithiel Cruz and Keren Tovar, from nearby Texas towns - also peer curiously at the concrete, steel and barbed wire.

Ithiel Cruz and Keren Tovar say they don't like the negative attention the border security debate is bringing to their region

They say they have no opinion about whether it's good or bad, but they don't like all the negative attention the debate over border security is giving their region.

"We were just in Houston recently, and they hear we're from the valley, and they're like, dang, how is it down there? You guys see a lot of crime or a lot of people coming over?" Cruz says.

"It's like honestly we don't really hear much about it. It's really good where we're at. We don't know why y'all are scared."

Statistics bear this out. Nearby McAllen, for instance, has the lowest crime rate in 34 years - with declines each of the past nine years.

The town's police chief, Victor Rodriguez, attributes the success to the totality of resources the federal government has dedicated to border towns - of which the already constructed border wall is only a part. The most valuable resource they've received, he says, is the human kind. The number of Border Patrol agents, external in the Rio Grande Valley region has grown from 392 in 1994 to more than 3,100 today.

"People can make arrests, people can deter, people can stop," Rodriguez says. "Fences and walls don't do that."

What's clear to him, however, is that McAllen and the towns around it are not in a state of crisis.

While they've seen a surge in undocumented migrants, placing some strain on city resources, the asylum seekers don't stay in the area. They head to the north and east, where the jobs, and their friends and family, live.

"They're going to Chicago, they go to New York or the big cities," he says. "They will be the ones to tell you whether this is a crisis or not."

Memories of a river

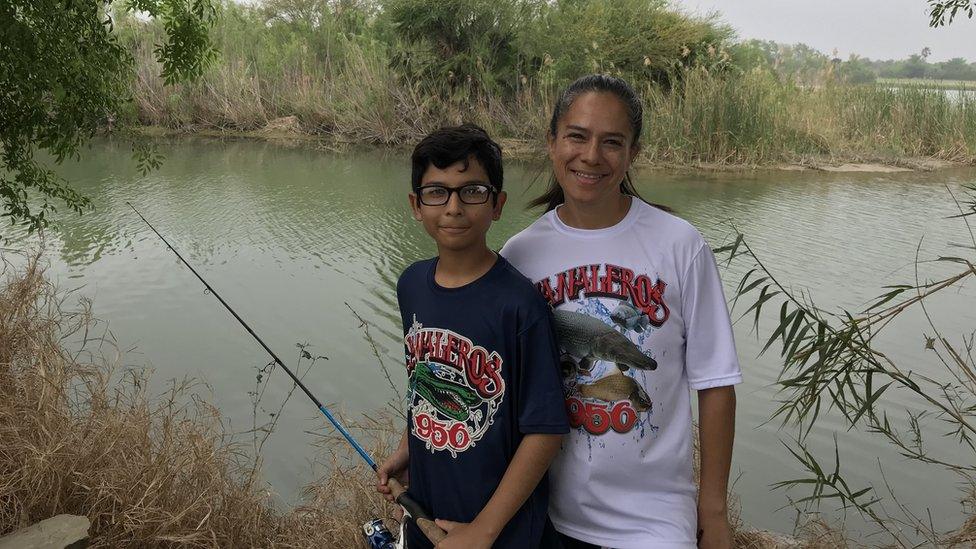

It's a misty morning in mid-March, and just a few bends down the Rio Grande from the butterfly centre Sandra Leal and her son Edgar sit on the banks of the river and fish.

Anzalduas Park is located at the point where existing border wall turns into planned wall. It's a peaceful bit of green grass, trees, picnic tables, barbecue grills and boat docks.

The night before, more than 300 migrants crossed the river just south of the park, where they were quickly taken into custody by Border Patrol. Now, however, it's quiet.

Sandra Leal wants her son Edgar to make memories in the outdoors and worries how a wall will affect their community

There's a park on the Mexican side as well, just a hundred metres away. People are fishing there, too, and a few faint chords of ranchero music can be heard when the wind blows east.

Leal says she enjoys spending time with her son by the river. Earlier in the day, she showed Edgar a map of the Rio Grande and explained how it stretches all the way from distant Colorado. He wondered if some of the water they were fishing in travelled the whole distance.

She said she liked to think so - that the river, the fourth longest in the US, forms a bond that runs deep into the heart of the country.

"Even if we don't catch a thing at all today, it's more about being connected to our natural beauty out here," she says. Playing indoors is nice, she says, but the outdoor memories - going fishing, visiting the butterfly centre, going to something natural - are the ones that last.

She worries that a wall will cut her community off from the river, and give her son a different kind of childhood memory.

"Taking the kids out fishing, seeing the open land, being able to show him Mexico right there… having a wall just takes away from our natural beauty," she says. "I don't want a memory to be based off this big wall separating us."

A family takes photos of flowers and butterflies at the centre

That's a concern filmmaker Ben Masters says he's seen play out all along the US-Mexico border. He and a group of friends travelled along the Rio Grande from El Paso to the Gulf of Mexico on canoe, horseback and mountain bike, recording their journey for the recently released documentary The River and the Wall.

"What I have seen in areas where there is a wall, people don't feel comfortable," Masters says. "There's a no man's land between the river and the wall where they're constantly harassed by Border Patrol. You know it's not an environment where people want to vacation."

Masters also notes the irony that the US fought a war with Mexico in the 1840s in large part to ensure access to the Rio Grande, the only major body of water in the region.

Now the country is essentially giving that land away.

By law the US government can't use the wall to block Americans off from their private property. Whether it's ranchers, homeowners, churchgoers or bird-watchers, the Border Patrol is obligated to construct gates along the length of the border wall to allow US residents to come and go as they please.

The butterfly centre's Wright promises to give her gate access code to every one of the 30,000 annual visitors and members of the preserve.

The reality, however, is that the wall - with its imposing steel, concrete and razor wire, under the watchful eye of uniformed government agents - could form a psychological barrier as much as it is a physical one.

That's the point Wright, in her lawsuit, is trying to make, that the wall creates more problems than it solves.

The government, she says, needs to take the people, and the animals, who live along the Rio Grande into full account.

"We appreciate the river," Wright says. "We know what an incredible resource it is both for our natural treasures, but also for our commerce, for our economy, for the amistad - the kinship - that we have on the other side."

The question is whether a judge will eventually agree.

- Published31 October 2020

- Published4 April 2019

- Published12 March 2019