Cultural appropriation: Why is food such a sensitive subject?

- Published

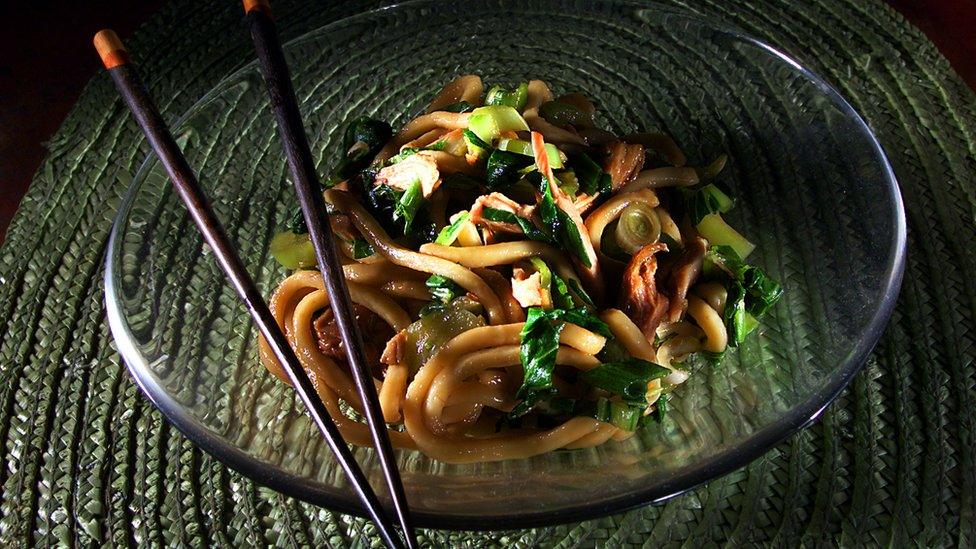

Earlier this week, a restaurant in New York made headlines for rather unfortunate reasons.

Lucky Lee's, a new Chinese restaurant run by a Jewish-American couple, advertised itself as providing "clean" Chinese food with healthy ingredients that wouldn't make people feel "bloated and icky the next day".

It told Eater website, external: "There are very few American-Chinese places as mindful about the quality of ingredients as we are."

It prompted a fierce backlash on social media from people who accused the restaurant of racist language, cultural appropriation, and a lack of understanding of Chinese food.

The restaurant's Instagram account was besieged with thousands of angry comments, including some which questioned the credentials of a white couple running a Chinese restaurant - as well as comments from defenders who accused the "online slacktivists" of being easily offended, and targeting the restaurateurs simply because of their race.

The whole debate became so polarised that ratings site Yelp placed an "unusual activity" alert on the restaurant's page after it was flooded with both positive and negative reviews, many seemingly from people who hadn't actually been to the restaurant.

Lucky Lee's has since issued a statement, external saying that it was not "commenting negatively on all Chinese food… Chinese cuisine is incredibly diverse and comes in many different flavours (usually delicious in our opinion) and health benefits".

It added that it would "always listen and reflect accordingly" to take "cultural sensitivities" into account.

The owner, Arielle Haspel, told the New York Times, external: "We are so sorry. We were never trying to do something against the Chinese community. We thought we were complementing an incredibly important cuisine, in a way that would cater to people that had certain dietary requirements."

The uproar is the latest in a series of rows over food and cultural appropriation.

US celebrity chef Andrew Zimmern came under fire, external for saying that his restaurant Lucky Cricket would save people from the low-standard "restaurants masquerading as Chinese food that are in the Midwest". Critics accused him of being patronising towards smaller restaurants run by immigrant families, and he later issued an apology, external.

Meanwhile, in the UK, supermarket chain Marks and Spencer was accused of cultural appropriation, external after it produced a new vegan biriyani wrap, despite the Indian dish normally being served with rice and meat.

And Gordon Ramsay's new London restaurant, external, Lucky Cat, was criticised for selling itself as an "authentic Asian Eating House" - despite not having an Asian chef.

When did food become such a sensitive topic - and why does it provoke such strong reactions from both sides of the debate?

Food can be closely linked to identity

For many people - particularly those from ethnic minority backgrounds - food can be both personal, and political.

Second and third generation immigrants often have "a sense of loss of their own culture - their attire is western, their language is western, and food is almost the last of the cultural domain that they retain a vivid memory of", Krishnendu Ray, a sociologist and professor of food studies at New York University, tells the BBC.

Many Chinese Americans have talked about their experiences growing up, external - for example when classmates would make fun of the food in their lunch boxes.

Luke Tsai, a food writer in the San Francisco Bay Area, says: "We grew up in the US with a sort of in-between status of our identity. Were we American? Were we Chinese? It was hard to find acceptance in a lot of mainstream culture.

He remembers being "slightly ashamed" of Chinese food when he was younger - "I didn't want to bring Chinese food for my lunch at school - I wanted a sandwich or pizza to fit in."

"People would say: 'Why are you eating that smelly thing? That's gross!'"

"But for many of us as we got older, we remembered the food our parents cooked us, and it became a great source of nostalgia for us - in a way, embracing that was embracing the Asian, immigrant side of our identity."

Many Chinese restaurants deliberately adapted their menus to serve more fried foods or thickened sauces because those were items a "mainstream white audience" were more familiar with, he adds.

"The reason that they opened those restaurants was not because they couldn't cook their 'true' Chinese food, it was because that was what they did to survive and cater to their audience.

"So to see that flipped around nowadays, and have a white restaurateur open a restaurant and say 'we're not like those Chinese American restaurants you know about, we're serving clean Chinese food… is particularly hurtful and offensive for a lot of people."

There's also a historical context to this. In the 1880s, the US passed legislation barring Chinese workers from immigrating to the US. Only a few categories were exempt - including restaurateurs - and historians say this contributed to a boom in Chinese restaurants, external in the US.

Yet "American exposure to Chinese food has mostly been cheap Chinese food", and the cuisine has been associated with "a kind of disdain" due to the presumption that it is associated with "cheap ingredients and mostly untrained labour", says Prof Ray.

"Very few Americans realise or know that China probably had the most sophisticated food culture in the world at least 500 years before the French did."

Whose food is it anyway?

Some of the sharpest criticism on both sides has been around ownership.

Some negative social media comments about Lucky Lee's have focused on the fact that the owners are white - while critics have responded that it would be ridiculous to suggest that only Chinese people are allowed to cook Chinese food.

Francis Lam, host of The Splendid Table radio programme, believes that a lot of the furore around cultural appropriation and food is due to a "disconnect in the conversation".

"I think if you're a chef or restaurant owner, it's fair to say you probably put a lot of yourself into your business, and don't want to hear it when you think people are saying 'you're not allowed to do that'."

However, he thinks that for those opposed to cultural appropriation, the issue is "not about who's allowed or not allowed to do things", but rather about the manner in which things are done.

"If you are going to promote yourself as someone who cooks or sells food from a culture you didn't grow up in, I would say it's also your responsibility to make sure you're doing it in a way that truly respects the people who grew up in the culture - and the people who frankly invented some of the things you're doing."

Andy Ricker says chefs need to be respectful - but also need a thick skin

Andy Ricker, an award-winning chef and bestselling cookbook author, spent 13 years learning about Thai cuisine, familiarising himself with ingredients and the language, before starting the restaurant chain Pok Pok.

He is recognised as an expert in northern Thai cuisine - and his approach has been praised by Asian chefs and food critics. However, others have also questioned why a white chef is being seen as the authority on Thai food, rather than a Thai one.

He suggests chefs should "be aware that language is important", and try "to be as accurate and faithful as you can".

"I can't say that I'm making authentic food because I don't have any claim to that."

The most important thing for chefs like him, he says, is to "be respectful and not claim anything is yours. Don't apply labels to food - don't just add chillies, basil and peanuts to something and call it Thai, or put something in a sandwich and call it Banh Mi… you're playing to clichés which is not a good look".

He also says it's crucial for chefs to "grow a thick skin - it doesn't matter what's in your heart or how careful you are about what you say, there's going to be people who just aren't having it."

Meanwhile, Chris Shepherd cooks a range of cuisines at UB Preserv in Houston, Texas, but says highlighting and cherishing the cultures that inspired him is important to him.

Chris's dishes include "boudin siu mai" - a take on a type of Chinese dumpling

His restaurant's bills come with a listing of his favourite local restaurants, and the message "we'd love to have you back at UB Preserv, but we politely request that you visit at least one of these folks first".

He acknowledges that his restaurant attracts more funding and publicity than many small businesses, but says his goal is to "get people who wouldn't normally go" to those places, or try different cuisines, to "visit these restaurants and become part of this community".

Why is it hard to separate food and politics?

These days, there seems to be constant debate about identity politics, and an endless stream of incidents provoking outrage. It can certainly feel tempting to keep politics out of food.

But commentators argue that the food business, like any other business, is linked to power structures and privilege - and it's not a level playing field for everyone.

"If you're opening a business you're already engaging with the public, making decisions about who you're going to hire, who can afford to eat at your restaurant, what your staff is going to look like - there's hundreds of decisions you're making that will have an impact on society," Mr Tsai says.

Meanwhile, Prof Ray says that his research suggests some ethnic minority chefs may face specific barriers.

"There is a tendency to 'ghettoise' Chinese, Mexican and Indian American chefs into cooking 'their own food', whereas white chefs tend to find it easier to cross boundaries", and are seen as "artistic" when they do.

Kwame Onwuachi, 29, has been nominated for awards for his cooking

Kwame Onwuachi says in his memoir, external that, during a casting session, a television producer told him that US audiences would not be prepared to see a black chef like him doing fine dining.

Similarly, chef Edourdo Jordan has previously told GQ, external that some people found it hard to believe he was the owner of a restaurant serving French and Italian food.

Mr Ricker agrees that white chefs face some advantages when cooking in the West.

"Of course in white dominant culture, white people always get away with more than other people. But I would say this too - if you're a westerner trying to cook in Thailand you're faced with a massive amount of scepticism and sometimes downright derision…. I think it's human nature for the dominant culture to pigeon hole people who're not of their culture."

It all comes down to money

These perceptions also have financial implications that affect restaurants' bottom lines.

In one study, Prof Ray found that dishes from certain cuisines were seen as more prestigious, enabling restaurants to charge more.

For example, an average meal at a Zagat-listed French or Japanese restaurant cost about $30 more than an average meal at a Zagat-listed Chinese or Southern restaurant in 2015, his research found.

Chef Jonathan Wu encountered this when he opened a high-end Chinese restaurant, Fung Tu, in New York.

The restaurant received excellent reviews, with Bloomberg calling the food "genius", external, and the New York Times giving it a two-star, "very good" review, external.

One of the dishes at Fung Tu - egg whites poached in a broth with Toona sinesis leaves

But Mr Wu says he received a lot of "blowback" for its prices, with complaints that the restaurant was "too expensive for what it is".

Fung Tu closed down in 2017, and was reopened as Nom Wah Tu, a dim sum restaurant with lower prices.

Mr Wu says there is still an "expectation that Chinese food is cheap".

He compares how hand-made Chinese dumplings are sometimes sold for "five for a dollar", whereas a high-end plate of ravioli can sell for "$45 a plate".

"If you tried that for a plate of dumplings, people would freak out."

Which would you pay more for?

Are things changing?

In a way, the whole cultural appropriation debate is also "a symptom of a very visible, assertive, middle and professional class" of people from ethnic minorities in the US, says Prof Ray.

And US perceptions of Chinese food could be radically different in 20 years' time, due to China's economic rise, and a growing Chinese middle class presence in US cities.

Prof Ray says a similar process happened from the 1980s with Japanese food, as the culture became associated with affluent immigrant groups or businessmen.

In the meantime, the cultural appropriation debate is likely to continue - but not everyone thinks that's a bad thing.

"We're experiencing growing pains in this whole conversation, but the bigger picture is that it's amazing to see how the American palate has widened, and there is a greater market acceptance of different stories and backgrounds," says Mr Lam.

"These conversations can seem frustrating and tiresome, but you have to have them."

Mr Ricker agrees. "There's a lot of angst, anger and defensiveness out there, [but] it's important that people understand the sensitivity around food and culture, because they're very powerful things. I don't think it's comfortable for anybody, but it's certainly necessary."

- Published15 September 2018

- Published3 March 2017