US college scandal: How much difference does going to a top university make?

- Published

Desperate Housewives actor Felicity Huffman is accused of paying $15,000 to have her daughter Sophia Macy's exam answers corrected

The US admissions scandal has seen dozens of people charged following claims wealthy parents paid bribes to get their children places at elite colleges.

But how much does which university you attend really matter?

Not much, according to research - and it looks as if it matters least of all for those from the most privileged backgrounds

Many affluent parents may be spending a huge amount of time, money, and energy to secure a bumper-sticker-worthy college place, with little by way of tangible results.

Instead, it is those from the most deprived backgrounds who stand to gain most but are least able to access places.

Future earnings

It is certainly true that the graduates of elite institutions earn more than those from less prestigious colleges.

But this is almost inevitable, given students with higher grades are more likely to be admitted to selective institutions in the first place.

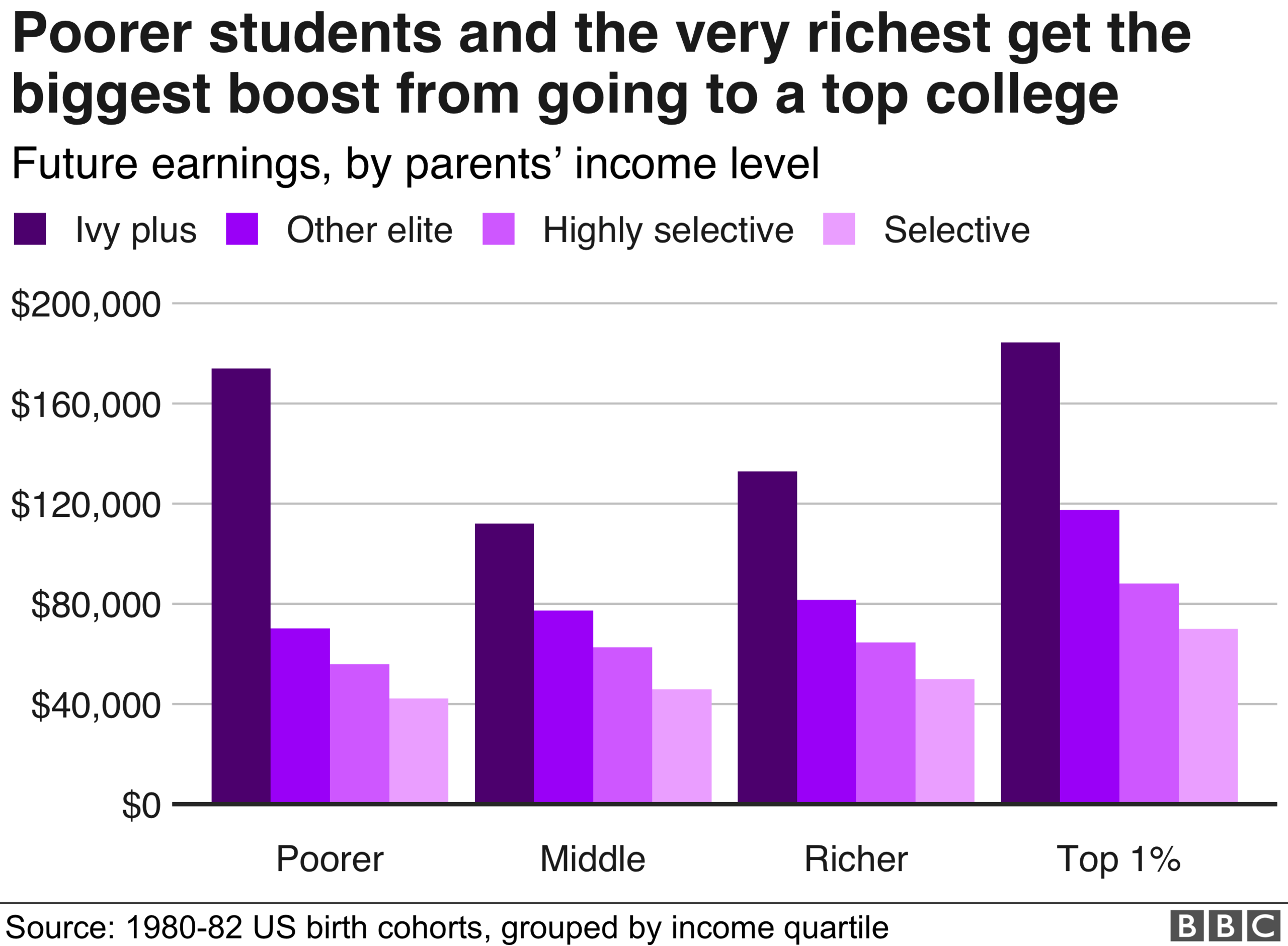

Those who attended a top college earn more than graduates from non-elite institutions by their mid-30s, including those from poorer backgrounds, data suggests.

For example, students from middle-income households who attended Ivy League colleges have average earnings of more than $100,000 (£77,500) by the time they are 34. These institutions - including Harvard, Princeton and Yale - have average tuition fees of about $55,000 (£42,600) and admit about one in 20 applicants.

This compares with earnings of about $40,000 (£31,000) for those who attended minimally selective schools.

The effect on earnings of going to a top university is greatest for students from households with the highest and lowest incomes.

Most of the colleges in the scandal (Yale and Stanford aside) are in the "other elite" category, where the income boost is lower.

However, it is perhaps unsurprising that many parents are tempted to do all they can to secure a place at a top college.

But, as their children will learn in Statistics 101, correlation does not equal causation.

The question is whether elite colleges themselves boost future earnings, or whether they simply select highly skilled students who would succeed anyway.

Most of the evidence suggests it is largely the latter.

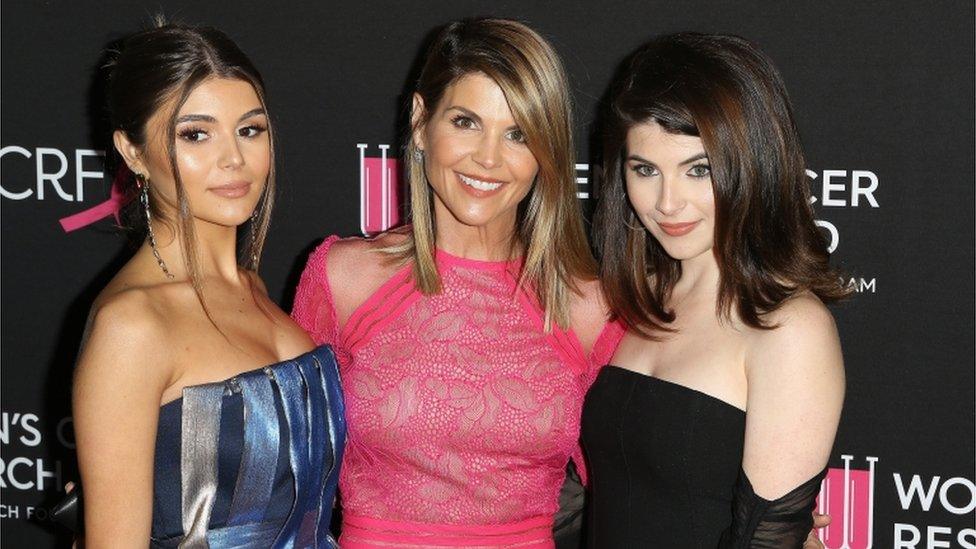

Lori Loughlin (centre) is accused of using a scam to get daughters Olivia and Isabella Gianulli, into the University of Southern California

Smart, motivated students who go to an elite college earn about the same as equally smart, motivated ones who go to a slightly less selective one.

Studies suggest that students admitted to a more selective college, external who then chose to enrol at a lower-ranked institution don't earn less in later years.

Not all researchers come to the same conclusion but most studies suggesting any causal effect of attending a more selective college find at most a modest difference.

In many cases, the choice of college major, external can have as big an effect as the college itself. For example, one study indicates selectivity is important for business majors but not for those in the sciences, external.

What is the college admissions scandal about?

The FBI believes $25m in bribes were paid to gain university places

Parents are accused of paying to have their children's test scores faked or for a fraudulent place on a university sports team

More than 50 people - including 33 parents and various sports coaches - have been indicted

Full House actor Lori Loughlin is alleged to have paid $500,000 to get her daughters on to the University of Southern California rowing team

Desperate Housewives actor Felicity Huffman is accused of paying $15,000 to have her daughter's exam answers corrected

Scheme architect Rick Singer presented himself as an expert in the university admissions process and has pleaded guilty to racketeering

Secondary schools

Similar results can be found for selective high schools - which, again, many parents are very anxious to get their children into.

Students who narrowly miss entry into competitive secondary schools in Boston and New York, external, for example, go on to do just as well as those who narrowly clear the hurdle, according to research - there is little difference in terms of their subsequent SAT scores, college attendance, college selectivity, and college graduation.

As with the colleges, it seems, it is not the schools driving the impressive results: it's the students they let in.

Prospective students tour Georgetown University in Washington DC

To be clear, none of this means that it doesn't matter at all which college you go to - simply that modest differences around selectivity don't seem to matter too much.

However, if a student turns down Yale in favour of an entirely non-selective local community college, it is possible they may not go on to do so well. This is especially likely if the community college lacks the resources to help students complete their degrees.

Most of the studies use earnings as the main measure of success.

And, of course, money isn't everything, as many graduates of the liberal arts console themselves.

Students at elite colleges may have better luck landing prestigious occupations, external - such as roles at top legal or financial firms. They may also learn the skills and make the connections, external needed to get such an occupation during their time in the ivory tower.

On the other hand, college graduates who attended more selective colleges actually report lower job satisfaction, external and are more likely to feel underpaid.

But if the overall story is that the status of a college seems to matter much less than the qualities of the students, there is one key exception to this general rule.

Students who are the first in their family to attend college, or who come from a minority background, appear to be the only groups who benefit from attending elite colleges.

How US university admissions are broken

First-generation students, for example, get about a 5% earnings bump if they attend a more selective college, research suggests.

One possible explanation for this is that these institutions give disadvantaged students access to networks more affluent students already have through their parents.

It looks, then, as if the students with the least access to top-ranked institutions may well be those with the most to gain. But fewer than one in 50 young people whose family are in the bottom 60% of incomes actually attend elite colleges, compared with about 40% of those in the top 0.1%.

The irony is that the privileged students whose parents stop at almost nothing to get them into elite colleges appear to gain little as a result.

And they may even be the ones taking the places of the lower income applicants who stand to benefit most.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from experts working for an outside organisation.

Richard Reeves is a senior fellow in economic affairs, external at the Brookings Institution. Katherine Guyot is a research assistant at Brookings.

The Brookings Institution, external is a not-for-profit public policy organisation, conducting research that leads to new ideas for solving problems facing society.

Edited by Duncan Walker.