John Walker Lindh: Anger as 'American Taliban' freed

- Published

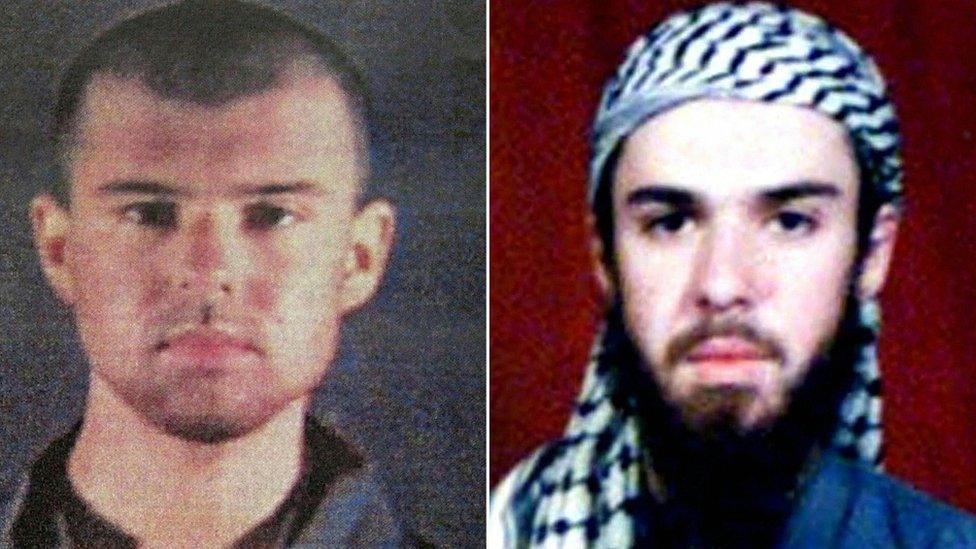

John Walker Lindh expressed regret for joining the Taliban in 2002, but people have raised doubts about this contrition

John Walker Lindh - the so-called "American Taliban" - has been released from prison, a move Secretary of State Mike Pompeo declared "unconscionable".

Lindh served 17 years of a 20-year sentence after he was captured in 2001 fighting in Afghanistan.

His early release has sparked fierce criticism, with many believing he still harbours extremist views.

President Trump said of the release: "I don't like it at all", and vowed the government would "watch him closely".

But he said: "From a legal standpoint, there's nothing we're allowed to do."

In an interview with Fox News on Thursday, Mr Pompeo said the move was "deeply troubling and wrong".

Lindh "still is threatening the United States of America" and was "still committed to the very jihad that he engaged in", he said.

Lindh's lawyer, Bill Cummings, told CNN his client would now move from his prison in Indiana to Virginia and live under the direction of his probation officer.

Who is John Walker Lindh?

Born in Washington DC in 1981 and named after John Lennon, Lindh was raised a Catholic.

He dropped out of school and converted to Islam at the age of 16, moving to Yemen the next year to learn Arabic.

In 2000, he went to study in Pakistan and eventually travelled to Afghanistan in May 2001 to join the Taliban.

John Lindh's father wants presidential clemency for his son

US forces captured and arrested Lindh shortly after the invasion of the country in the wake of the September 11 attacks.

"Had I realised then what I know now about the Taliban, I would never have joined them," Lindh said during his sentencing in 2002, on a charge of aiding the Islamist militant group.

Is Lindh still an extremist?

There are concerns that Lindh has not abandoned his extremism.

Foreign Policy magazine published US government documents in 2017, external stating that the prisoner "continued to advocate for global jihad and to write and translate violent extremist texts".

And in March last year, Lindh "told a television news producer that he would continue to spread violent extremist Islam upon his release", the documents allege.

More recently, The Atlantic magazine's journalist Graeme Wood wrote letters to Lindh while he was behind bars and describes him as "unrepentant", external.

"His more than 17 years in captivity seem, on the basis of this correspondence, to have converted Lindh from an al-Qaeda supporter to an Islamic State supporter," Mr Wood wrote.

Released into a world unprepared for his arrival

By Tara McKelvey, BBC News, Washington

After his release John Walker Lindh, now 38, will not be allowed to go online unless he has special permission, and he cannot travel freely.

He will discover a world that has changed dramatically since his incarceration and face a society that has done little to prepare for his arrival.

The US government does not have an official programme or set of procedures to help people convicted of terrorism find their way in the world after their release.

Many experts, including the Federation of American Scientists' Steven Aftergood, who specialises in national security, say the US should do more to help.

"In the justice system, we say 'You, the criminal, are not like us'. But there is also a responsibility for society to say at the end 'There is a place for you in our world'. We're very bad at that."

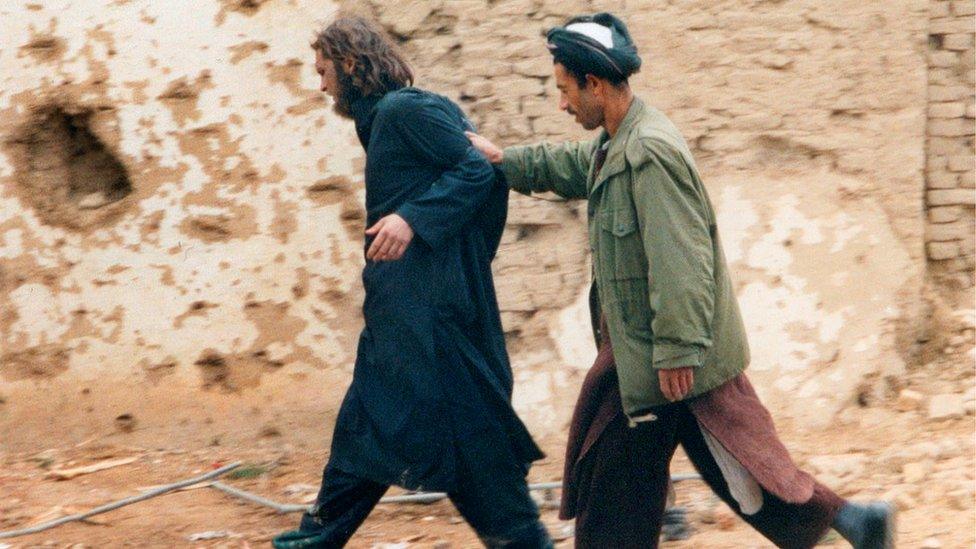

John Walker Lindh, left, was captured by Northern Alliance Afghan forces in 2001

Can Lindh reintegrate into US society?

Senators Richard Shelby and Maggie Hassan - a Republican and a Democrat, respectively - wrote a letter on Friday to the Federal Bureau of Prisons asking how to handle such cases.

Obtained by the Washington Post, the letter urges the group to consider "the security and safety implications for our citizens and communities who will receive individuals like John Walker Lindh", external.

But others are less concerned. Investigative journalist Trevor Aaronson says Lindh is the 476th person convicted of terrorism after the September 11 terror attacks who has now been released.

"To be clear, the federal government has no program to monitor released terrorists - suggesting that convicted terrorists can be rehabilitated completely, external after relatively brief sentences or that many of these people weren't particularly dangerous in the first place," Mr Aaronson tweeted.

- Published30 September 2011