How the 2019 coffee crisis might affect you

- Published

In 2019, a latte - foam art and all - costs the average US coffee drinker around $5 (£4). So why are the farmers who grew the beans behind your morning brew abandoning their plantations for different crops, different jobs, or even to seek asylum in a different country?

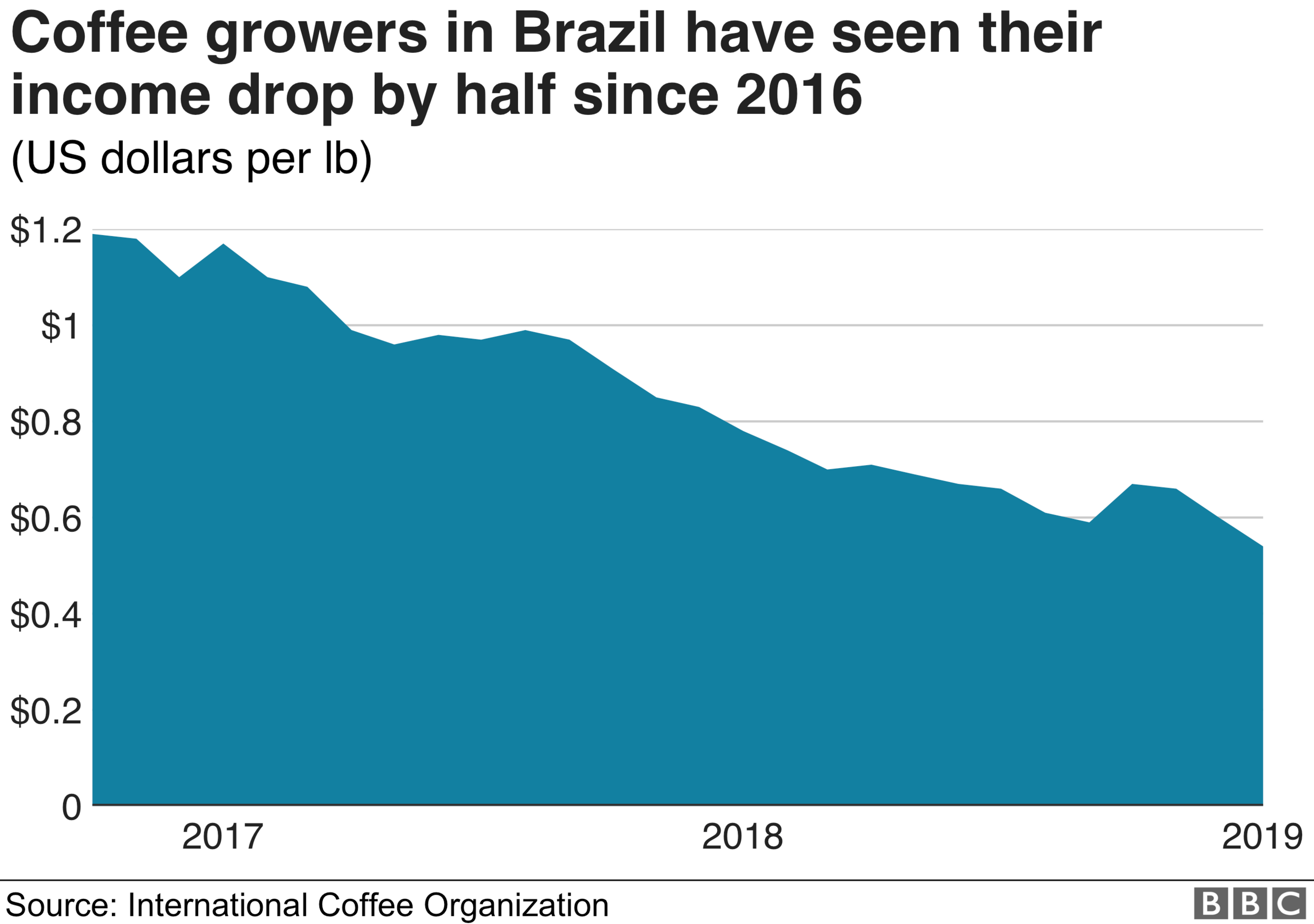

The world's coffee industry is in crisis. This May, coffee prices fell to their lowest point in over a decade at $0.88 (£0.70) per pound.

The dip is largely due to two years of surplus from Brazil, the world's largest coffee producer, which has had a serious impact on growers around the world by pushing millions of kilograms of beans onto the market. Economic issues in coffee-producing regions like Central America and Africa are also at work.

As of mid-July, market prices have crept up to around $1 - but it's still not far off the lowest price the industry has seen in 10 years, external.

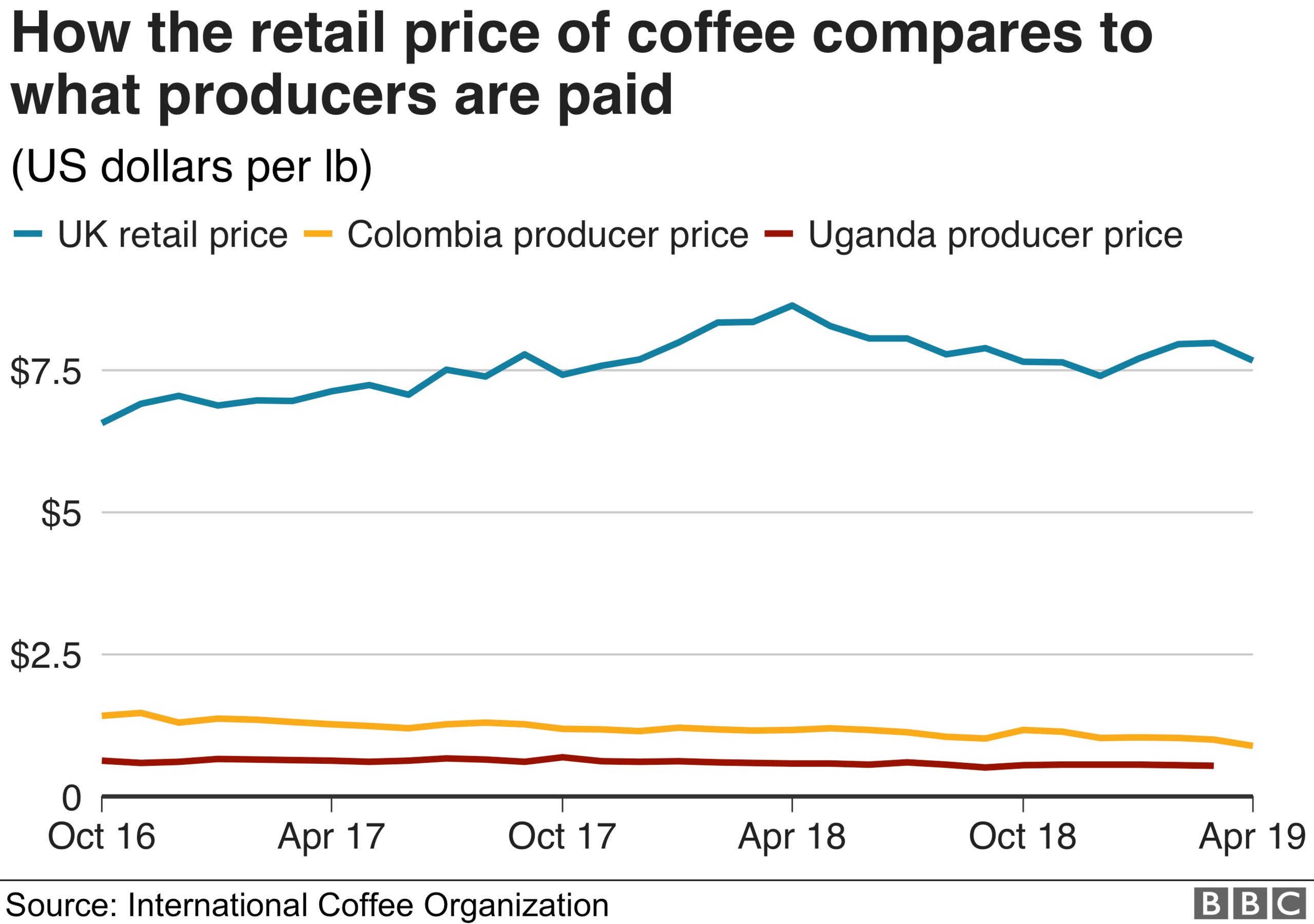

But in recent years, consumers in the US and UK have seen the price of a latte rise - even though farmers see less than 2% of those profits.

Here's how the crisis is playing out at each link in the coffee chain.

For farmers

Globally, over 21 million families make a living from coffee. Plantations generally see one major harvest per year, so high and low cycles are expected, but the 2018-2019 production year's price has dropped to historic lows, making it much harder for farmers to weather.

To simply break even, most farmers must sell a pound of coffee for over $1.

In October, a number of Central American farmers travelling with the migrant caravan to the US told BBC journalists that the coffee crisis had forced them to abandon their farms and to try to seek asylum in the US.

In the last 10 years, over 60% of coffee farmers in Guatemala, Nicaragua, El Salvador and Mexico have reported food insecurity during the harvest cycle, according to the Specialty Coffee Association of America, external.

José Sette, executive director of the International Coffee Organization (ICO) - which was founded in 1963 with the support of the United Nations to address sustainability in the coffee commodity market - told the BBC this current low cycle was so concerning to the entire industry precisely because of its "dramatic" effect on growers.

"If farmers are discouraged today and they are not planting, not taking care of their trees…that bodes very ill for the future, since demand is increasing about 2% each year," Mr Sette says. "That's 3m bags more that we need every year to satisfy demand."

Mr Sette adds that while the world coffee industry sees revenues over $200bn each year, only $20bn reaches producing countries and ultimately, less than 10% of that reaches growers.

"When we get to the level of prices that we are seeing today, the industry needs to look at itself and try to find ways in a spirit of shared responsibility, to somehow improve the lot of the coffee farmers. Especially the smallest farms."

Across Africa, where the market is largely made up of these smaller, subsistence farms, this cycle is proving exceptionally challenging.

"In Africa we are likely to see a lot more suffering than elsewhere because our yields are quite low," Fred Kawuma, Secretary General of the Inter-African Coffee Organisation (IACO), told the BBC.

"The amount of coffee that a farmer gets out of his farm is so limited compared to, for instance, an Indian or Vietnamese coffee farmer."

Coffee on a farm in Ethiopia

This means when coffee prices decline, so does a farmer's already small profit margin, making it impossible to pay for household needs like school and healthcare.

This year, Mr Kawuma says his organisation is seeing many struggling farmers abandoning coffee for other, more lucrative food crops.

"Cote d'Ivoire is one of the countries that right now is having severe consequences - the farmers are not happy," he says. "Togo, smaller producers like Liberia, Sierra Leone - all the smaller countries are doing very badly and are not sure that they can really continue in production."

For roasters and cafes

Chuck Jones knows this industry from both sides: He owns a roastery and cafés in Pasadena, California, but around half of his beans come from his family's farms in Guatemala - one that is his and two owned by his cousins.

But at the end of July, one of his cousins in Guatemala is expected to lose his farm.

"The exporter, who he has a debt with for covering two harvests, is taking over the farm because he hasn't paid," Mr Jones says.

Chuck Jones' cousin Andres Fahsen at his farm in Guatemala

He says the "boom and bust cycles" of coffee pricing unfairly hurt growers like his cousin, who stand to make money only a few times each decade, especially given the access to cheaper options in the commodity market.

"As a buyer, I can easily replace that [coffee]," he adds. "But it hurts because it's my cousin, and he's losing his source of income. He's middle aged and he's been living off of the farm.

"Even though my cousin is a high quality, specialty coffee producer, he's still going to lose the farm because of the systems in place to prevent him from being able to succeed."

Mr Jones says industry leaders have been pointing out that roasters need to pay more. But to Mr Jones, who operates a business in a city with a high cost of living and high price for labour with a $15 hourly minimum wage, "there's no clear winner in the chain".

Included in his $10 price for wholesale, roasted coffee are numerous shipping and ongoing warehousing expenses, labour, machine upkeep and other financing costs.

For consumers

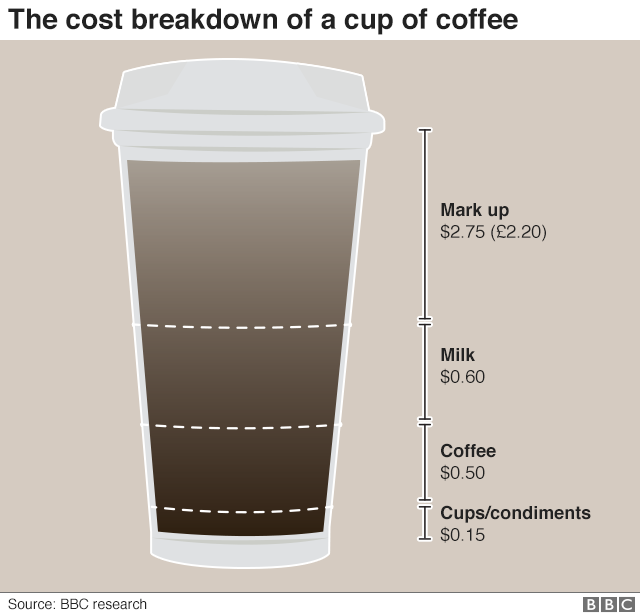

So how exactly does the price of a latte break down for consumers?

Mr Sette of the ICO explains that the retail price of coffee "is not very linked to the price of the physical growers".

"The amount that reaches the grower is 1-2%, but things like labour and rent, marketing, all of those occupy a big share of the final price."

WATCH: What does a $75 cup of coffee taste like?

Mr Jones broke down the price of retail coffee at his Pasadena cafés, and for a $4 latte, only the cost of coffee - 10% - is within Mr Jones' control. Organic milk, labour, cups, lids, sleeves, and coffee condiments all factor in.

"I don't think anybody is laughing their way to the bank," he says.

Across the country in New York City, the Think Coffee café chain's Coffee Director Enrique Hernandez told the BBC making a small latte costs the company $0.28, and is sold for $4.25 in order to pay for non-coffee costs.

That price will be going up to $4.50 this year, Mr Hernandez says, due to higher rent and minimum wage expenses.

Looking for solutions

The ICO and other industry organisations are working on changes like diversifying small farm incomes with other sources of revenue, teaching risk-management, streamlining production chains, and combating climate-change by adopting environmentally smart agriculture.

"We need to also promote consumption of coffee in coffee-producing countries, where it is often low," the ICO's Mr Sette adds. "A promising approach for, at least, the specialty coffee sector is to foster direct relationships between growers and roasters."

UK Latte Art Champion Dhan Tamang demonstrates latte art during the London Coffee Festival 2019

Higher end coffee companies like Think Coffee and Intelligentsia are examples of that partnership.

Mr Hernandez visits one of the farms Think Coffee buys from every three months. He says the company focuses on finding "vulnerable" farms rather than just buying from wealthier owners, and spends money towards building better living conditions for the farming families they work with.

Intelligentsia, which has cafes across the country, has similar practices to improve sustainability, including directly sourcing beans from Central and South America and Africa and hosting workshops for farmers.

Others in the industry have also called on big buyers, like Nestle, to pay fairer prices and not flood the market with low-quality, cheap coffees. Nestle told the BBC in a statement that it also offers training for farmers, and as "no one company or organisation can solve this issue", it is working with groups like the ICO "looking for practical and effective collective action".

Speaking at the World Coffee Producers Forum's 2019 conference in Brazil this week, Columbia University economist Jeffrey Sachs called for the establishment of an annual, United Nations-level, $10bn global coffee fund.

It's a hefty ask considering the global AIDS fund received just over $7bn in contributions from 2017-2019. But as coffee growers are forced to weigh other options simply to survive, the spectre of abandoned plantations around the world could be enough to motivate new changes.

As Mr Sette of the ICO says: "If we don't have the investments today, we might not have sufficient coffee in the future."

Additional reporting by Kelly Rissman

- Published21 January 2019

- Published2 June 2019

- Published1 February 2019

- Published13 April 2018