Key to a happy retirement? Fun housemates

- Published

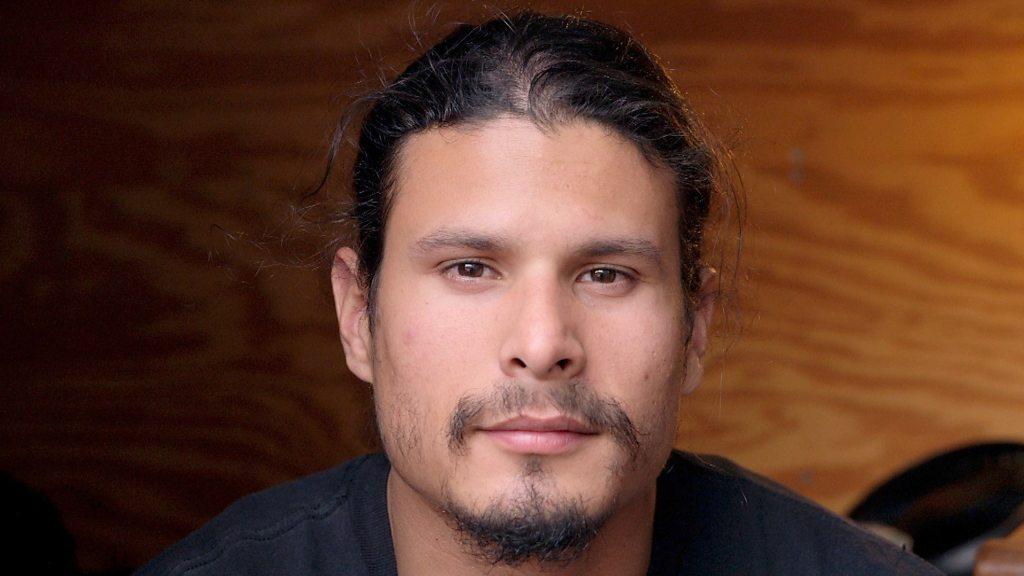

Meet housemates Louise, Martha, Beverly and Sandy

Four Canadian pensioners say the secret to a happy retirement is good housemates - and two dishwashers.

Betty White and Beatrice Arthur made it look like fun on the popular sitcom the Golden Girls, but what's it really like to share a house with others in your senior years?

"I've been amazed at how good it is," Louise Bardswich tells the BBC.

Bardswich has been sharing a 4,000-sq-foot home with three other women in Port Perry, Ontario, since 2015.

The four of them - Bardswich, 67, Martha Casson, 70, Beverly Brown, 68, and Sandy McCully, 74 - have become evangelists for this kind of housing, and have been dubbed the "Golden Girls" by Canadian media.

While it's not unusual for relatives or close friends to move in with each other as they age, they believe their situation - the four women were all relative strangers - is the start of a new trend.

The idea first struck Bardswich when she had to move her own mother into a retirement home. She had worked with Casson, and the two would talk about the struggles they were both facing caring for their aging parents, and planning for their own retirement.

"It was kind of a window into our futures," Bardswich says.

Bardswich did the maths for herself, and quickly realised that with inflation, renting in a retirement home would totally deplete her savings. She was also worried about the toll taking care of her would take on her children.

"My kids are lovely, but I knew what it felt like to have to do that for my mom, and I didn't want them to have to go through that," she says.

Beverly Brown, Louise Bardswich, Sandy McCully and Martha Casson have been nicknamed Canada's "Golden Girls" by the media

Interest in co-living for older people has risen as property rates in many areas around the world have skyrocketed along with the ageing population.

By 2036, one in four Canadians is expected to be over the age of 65.

According to a report by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities, about 700,000 senior-led households currently struggle with housing affordability. It is especially challenging in more rural communities, where there is limited housing stock as it is, and people may have to move far away from their social network in order to find appropriate accommodation.

In northern Ontario, a Facebook group for senior living looking to find housemates has attracted almost 1,500 members.

Across the pond, a group of women moved into the UK's first co-op housing designed specifically for elderly women in 2016.

The housing project had been in the works since 1998, but it encountered several planning hiccups along the way.

"I don't think British society was ready for it, a group of women who were going to take their own destiny in their own hands," Maria Brenton told the BBC's Sophie Long in 2016.

The women of Port Perry encountered similar setbacks.

When a builder applied for a permit to build a six-bedroom shared-ownership home in 2013, the township went as far as to try and pass a bylaw to outlaw this type of communal housing.

Casson filed a human rights complaint, and two hours before council was set to vote, Ontario's human rights commissioner sent a scathing letter condemning the proposed bylaw, and reminding officials that that it is against the law to discriminate "directly or indirectly against groups protected by the (Ontario Human Rights Commission). This includes the obligation to accommodate the needs of older people, people with disabilities and other needs relating to (OHRC) grounds."

The women finally got their home, at a different building site, in 2015.

The historic home was originally built by housemate Beverly Brown's great-great grandfather in 1855

They're all very frank about the inevitability of ageing. They've designed the house so that they could "age in place", and not have to move because of physical limitations.

This meant updating the home by installing an elevator, making the bathrooms accessible and leaving two bedrooms open for future live-in nurses.

"We talked about how we did not sign up to be each other's caregivers. When you need help, you're going to have to pay for the help, and if you can't be accommodated in the house with the help than that's the time you'll have to move," Bardswich says.

The house is also designed to allow each woman as much independence as possible. Each person owns 25% of the property - if someone dies or moves out, their share would be put on the market.

In addition, they each pay $1,500 a month towards living expenses, which includes a weekly house cleaner, landscaping, food and wine.

They all have their own large bedroom, with a TV and seating area and a bathroom. They share a living room and dining room and large kitchen, complete with two dishwashers, which helps them avoid kitchen squabbles.

"We agreed we would live our own lives. We're all pretty busy and out all the time," Bardswich said. But that doesn't mean there isn't time for communal suppers, or wine on the porch.

Each woman has brought a unique set of life experiences to the group, which they say makes the living situation even more fulfilling.

Between the four of them there are 13 grandchildren, who all come by to visit. Two of the women are widowed, two are divorced. In the summer, they've let theatre students who are in town working in local productions stay in their spare rooms.

Brown, who divorced in 1994, says she was initially hesitant about sharing a home after 25 years of living on her own.

"The surprising thing is what I enjoy the most is the company," she says.

The secret to co-living bliss? Two dishwashers and a regular house cleaner

Since moving in, the four women giving regular talks to other older people thinking about sharing.

They say their best advice is not to wait, but to plan for your future before others have to plan it for you.

Bardswich likes to advise people to find housemates with similar values - "a Republican and a Democrat shouldn't live together".

But Casson is quick to point out that between the four of them, two are actively religious and two are not.

"You can have some fairly fundamental differences, as long as you have some of the common values," she says.

- Published3 February 2016

- Published28 February 2018