Kamala Harris-Joe Biden row: What is desegregation bussing?

- Published

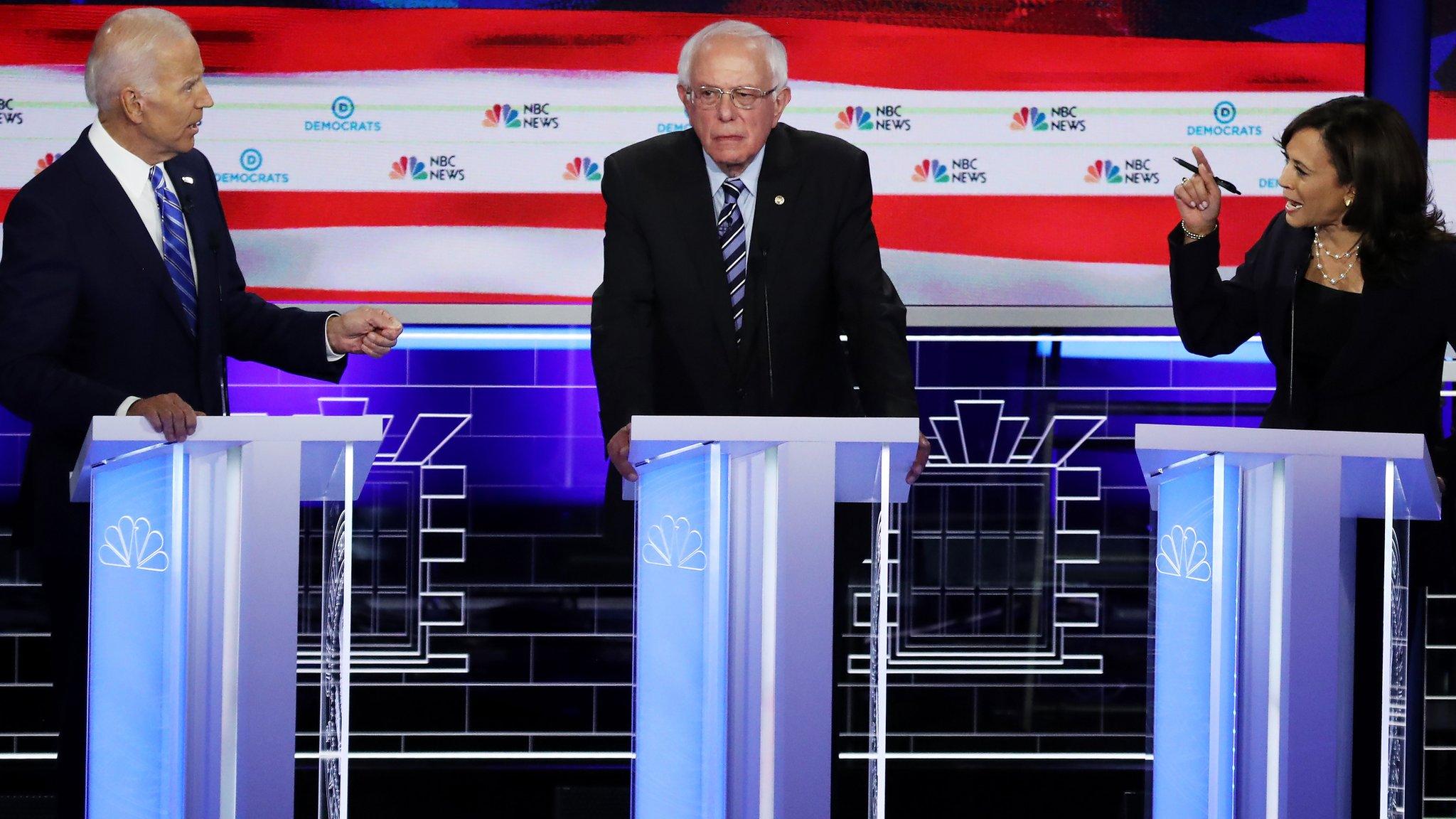

Senator Kamala Harris took on 2020 frontrunner Joe Biden during Thursday night's debate by highlighting his controversial history on the practice of desegregation bussing. So what is it?

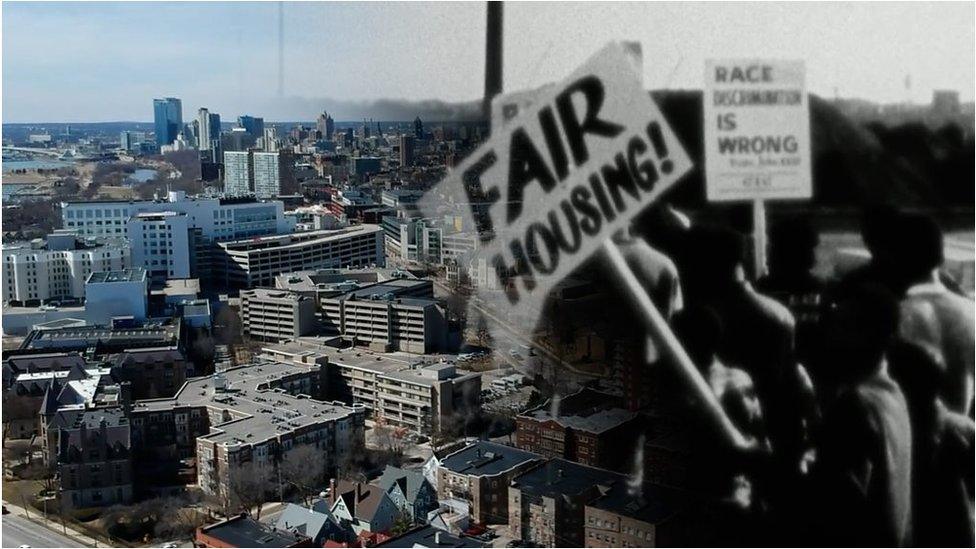

Desegregation bussing (also known as forced bussing) is the practice of transporting students to schools in different neighbourhoods in an effort to address racial segregation.

Bussing in general had been around for a long time, used to shuttle students from rural areas to larger, more consolidated schools, but it became controversial when race came into play.

In 1954, the Supreme Court found racially segregated schools to be unconstitutional in the landmark Brown v Board of Education ruling. Before Brown, schools for black children were typically inferior to white schools and received far less funding from states, external.

Desegregation bussing began several years after. Initially, it only involved moving black and Latino students into white schools.

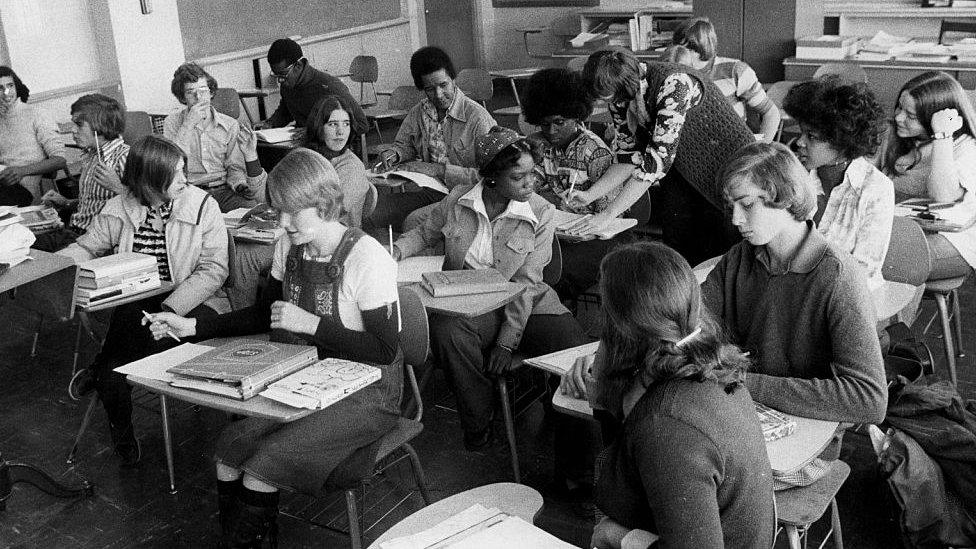

By the 1970s, the method had evolved in some districts into two-way bussing, where white students were bussed to minority schools and black and Latino students were transported to white-majority schools.

Harris and Biden clash over his race record

Was it successful?

Bussing and, later, two-way bussing, elicited pushback from white parents and politicians from the late 1950s through the 1980s.

"Both were controversial," says Dartmouth College Prof Matthew Delmont, a historian and author of the book Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation.

"Anti-bussing protesters didn't always distinguish between the two, but districts where they were trying to do two-way bussing programmes saw even more protests."

An initiative to desegregate Boston Public Schools in the fall of 1974 was met with strong resistance from many white residents

The very first anti-bussing protest, he says, was in New York City in 1957, where white parents opposed a plan to send a few hundred black and Puerto Rican students from their overcrowded school into a predominantly white school.

As the practice of bussing expanded, with court orders for cities to desegregate schools, more massive protests took place across the country, with notably violent ones in Boston, Massachusetts, Pontiac, Michigan, and Louisville, Kentucky.

Students were attacked with bricks, buses required police protection, and lawmakers came under increasing pressure from white voters to end the policy.

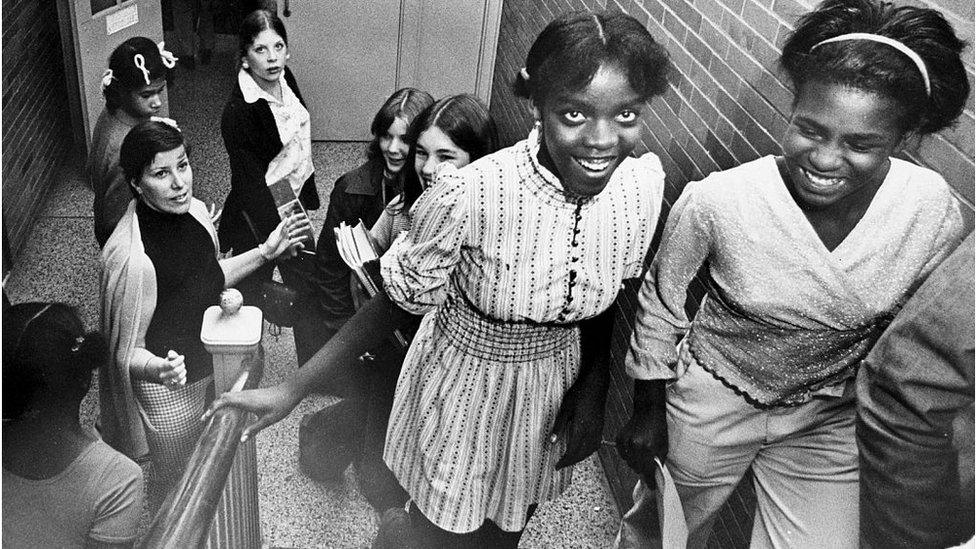

But even so, for students, the practice was successful when it was properly implemented.

Minneapolis, Minnesota, Berkley, California, and Raleigh-Durham, North Carolina, were all examples of cities that found a way to work through the initial upset and integrate, Prof Delmont explains.

"The actual experience of students tended to be quite positive once these plans go past the controversies," Prof Delmont says, noting that studies following up on these students found they were beneficial in particular for students of colour.

"That's what Kamala Harris was talking about."

A 2016 report on Boston's still-ongoing voluntary city-to-suburb bussing programme, Metco, found that 98% of participating minority students graduate on time, and most score higher on state tests than their city school peers.

However, many Americans saw the 1970s as proof that desegregation bussing was "a failed endeavour", he says.

"There's a disconnect between how it played out for students, which was positive, and the way it was talked about in media and political circles, which was a story of failure."

Is it still happening?

The practice of forced bussing declined in the 1980s, though some schools are still under court order to continue bussing, according to Prof Delmont.

But it is not as widespread, and schools are becoming segregated again.

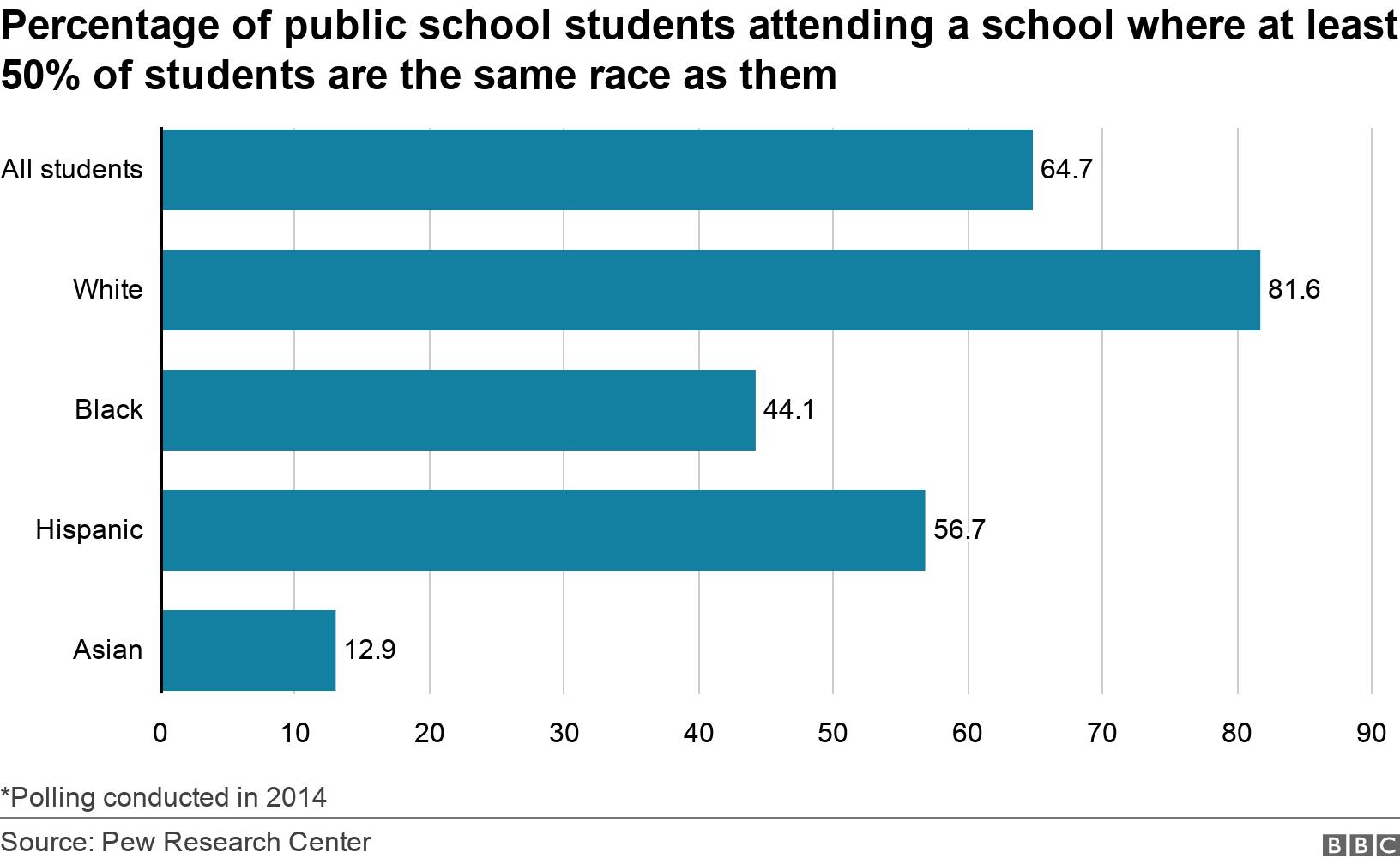

A 2014 study by the Pew Research Center, external found that close to two-thirds of all US public school students attend schools where most students are the same ethnicity. The percentage is highest for white students at 80%.

Despite successes with voluntary bussing, a 2018 Boston Globe analysis, external found 60% of Boston schools to be "intensely segregated".

Other options for desegregating schools have come up in recent years, but they have met with limited implementation and success.

Magnet schools - public schools that are given additional resources to attract diverse students - are one solution. As most public schools are organised by district geography, changing zoning policies is another way to reconfigure the demographics of a school system.

"Today, the schools that are doing the best are the ones where school officials, parents and politicians have shown leadership in terms of making the case that this is a civic good," Prof Delmont says.

But it takes time to see improvements, and for Prof Delmont, the impact of the backlash against bussing is still readily apparent in the way US schools look today.

African Americans in New Orleans on the state of race relations

If bussing had received more support from school officials and politicians, they could have resulted in "more meaningful integration", he says.

"If there had been a larger effort to integrate in the 70s and 80s it would have led to better career opportunities for more people of colour and one small step towards lowering the racial wealth gap we see."

So what did Biden do?

Ms Harris accused the former vice-president of supporting segregationist senators and opposing bussing - an issue close to her heart as she herself was bussed to school every day, a part of the second class to integrate public schools in California.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Mr Biden has since denied opposing bussing overall, saying he was only against it being ordered by the Department of Education, and insisting he supported federal actions to fix segregation and had fought for civil rights throughout his political career.

Joe Biden defends his civil rights record

In 1975, Mr Biden did sponsor a bill to ban the use of federal funds for bussing, though his campaign has also argued that Mr Biden's senate proposal would not have affected Ms Harris' school district.

"It was a microcosm of how the bussing issue played out over the last several decades," Prof Delmont said of the Harris-Biden discussion.

"What I mean by that is, the people whose voices were heard most tended to be white parents and politicians. We didn't often hear much from students and particularly not much from students of colour.

"That generational gap between Harris, as someone who lived through it as a student, and Biden, who lived through it as a politician - that was revealing."

- Published28 June 2019

- Published4 April 2018

- Published2 June 2017

- Published27 July 2015