Why do Americans pay so much for prescription drugs?

- Published

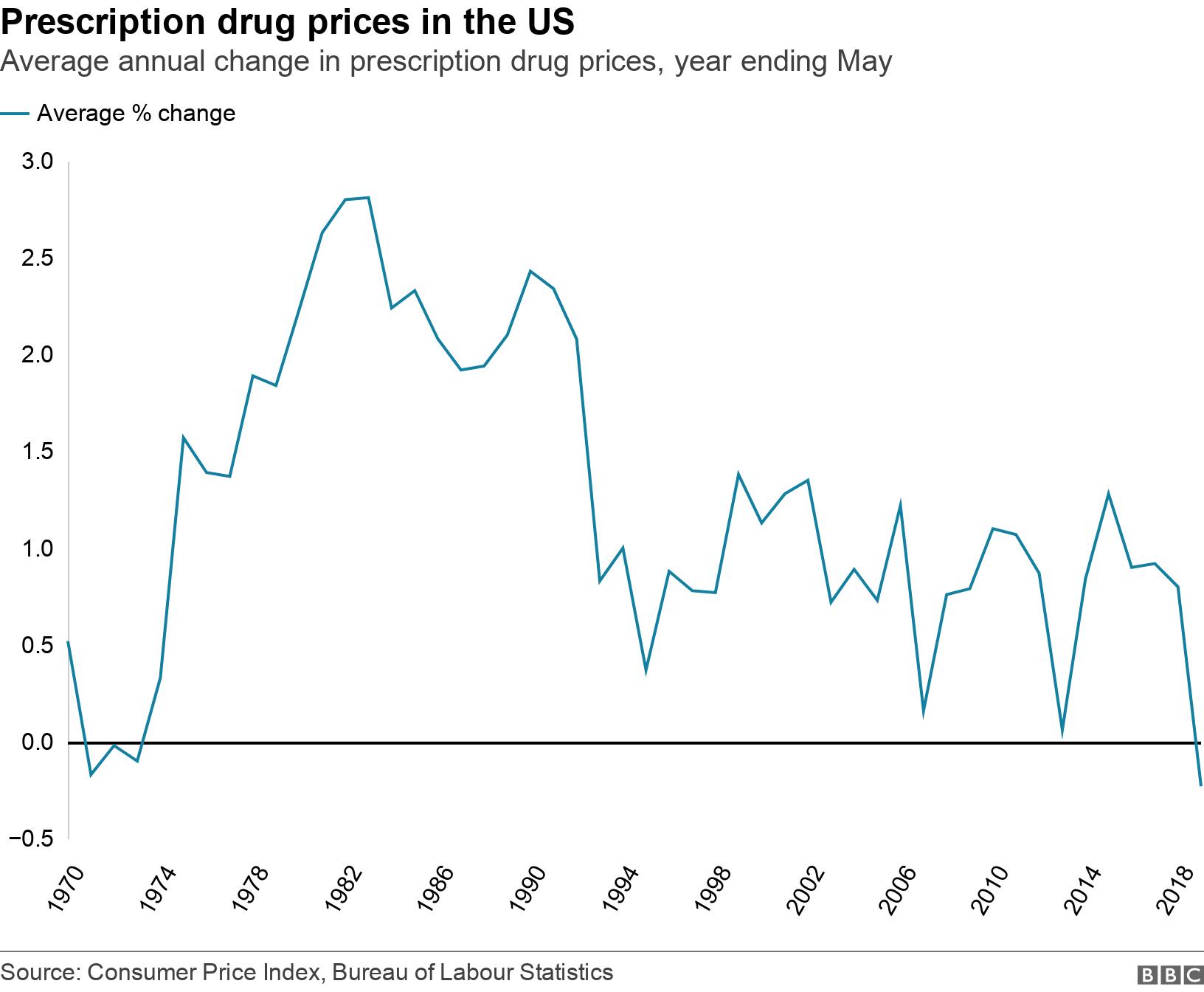

President Donald Trump said that prescription drug prices dropped for the first time in half a century in the US last year.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Since taking office, the president has made repeated attacks against those who set drug prices and has pledged to take radical steps to reduce them.

Have drug prices decreased?

Mr Trump appears to be referring to the Bureau of Labour Statistics Consumer Price Index (CPI), which measures the increase in the cost of household items in the US.

In the year to May 2019, the average monthly cost of prescription drugs fell by 0.2%.

This is the first price decrease over a 12-month period since 1973, some 47 years ago - so by this measure, his assertion is broadly correct.

However, this is not the most reliable way to measure drug prices according to Inma Hernandez, a pharmacy lecturer at the University of Pittsburgh.

"The CPI is based on a basket of drugs which is representative of popular drugs. So it tends to include widely-used drugs, which are usually cheaper," she says.

"However, it is less likely to include newer or less-prescribed drugs, which are more expensive and have higher price increases."

Additionally, this basket of goods is based on the price that pharmaceutical companies say they are going to charge for products, or "list prices".

In the US, individuals are encouraged to get health insurance plans because very few people have access to free healthcare.

These "list prices" are then negotiated down by insurers as an incentive to offer the drugs to patients.

So, even if the list price goes down, it is not known whether the actual price paid by insurers has decreased with it.

This affects patients because in the US, health plans contribute to some of the costs of the drugs they cover, although they will also have to make some out-of-pocket payments.

In theory, if insurers are paying less for their drugs, these savings will trickle down to those on health plans and reduce these out-of-pocket or insurance payments.

Given a general lack of transparency on drug price negotiations, it is very difficult to assess this aspect of medicine costs.

What other evidence is there?

Some companies, including Pfizer, Bayer and Allergen, publically committed to lowering or freezing costs last year.

This was after a series of comments made by Mr Trump.

"He thinks because he has made a lot of noise, it has prevented drug prices from increasing. It is not clear whether that is the case or not," says Ms Hernandez.

However, an Associated Press analysis of drug list prices, external found that for every drug which reduced in price in the first half of last year, 96 increased.

The investigation did note that the increases "were not quite as steep as in past years".

Why are drugs expensive in the US?

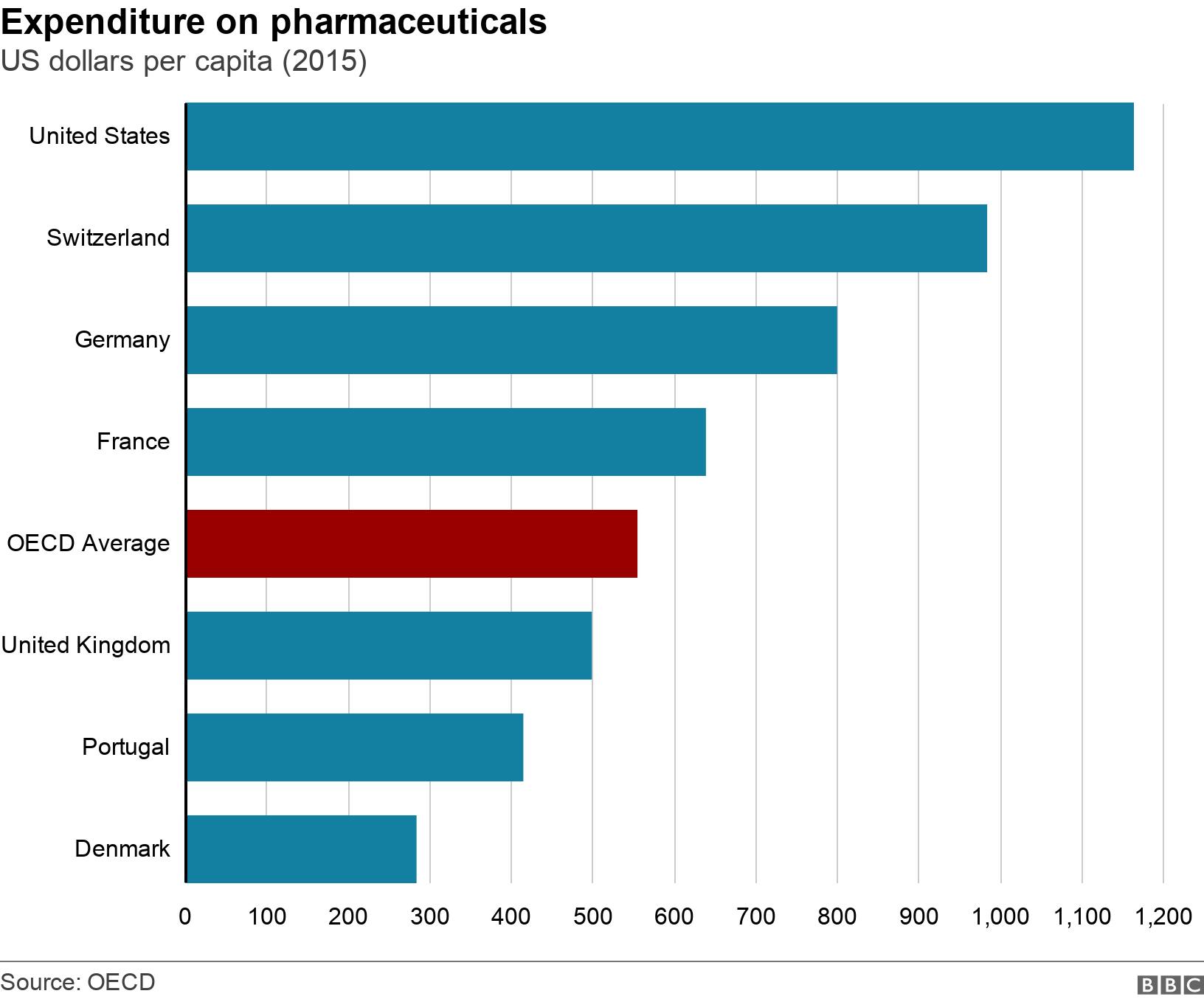

According to a report by the OECD group of industrialised nations,, external the USA spends roughly twice the average amount spent by other member countries on pharmaceuticals per head.

For example, where the UK paid £398 ($497) per head in 2015, the USA paid $1,162.

This is despite having similar prescription drug usage.

"One reason the UK pays less is because the government will say no to new drugs which don't offer much better value," says Prof Michelle Mello, a health policy specialist at the Stanford Law School.

"We don't have a government that buys drugs in the US, except in a few cases," says Prof Mello.

Instead, insurers use middlemen called pharmacy benefit managers - or PBMs - to negotiate prices on their behalf.

Because they are generally larger than individual health insurers, they are seen to have more purchasing power.

But the Trump administration has criticised them in the past for not passing on enough savings to consumers.

In England and Wales, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence represents almost all patients, so the drug companies have to lower their prices to access the market.

In Scotland, the Scottish Medicine Consortium performs the same role.

What is Mr Trump doing about it?

The Trump administration is exploring a number of policies either through ad hoc announcements or through an initiative launched last year called American Patients First.

These policies are generally aimed at decreasing prices for government health plans such as Medicare, the insurance policy used by almost 60 million elderly and disabled Americans.

Policy recommendations have included:

Introducing a flat fee for PBMs so more savings are passed on to consumers

Encouraging foreign countries to pay more for US medicines

Increasing the approval and prescription of generics - copies of more expensive brand-name drugs where the patents have expired.

One plan to force drug companies to reveal the cost of drugs in television adverts was recently blocked by a judge.

"The big blueprint the White House put out had a fleet of policy ideas which were evidence-based. However, not many of them have crept in," says Prof Mello, citing the difficulty in passing legislation in a divided and clogged Congress.