US expands powers to deport migrants without going to court

- Published

Rights activists protesting against ICE near the organisation's headquarters in Washington DC last week

The US government is introducing a new fast-track deportation process that will bypass immigration courts.

Under the new rules, migrants who cannot prove they have been in the US continuously for more than two years can be immediately deported.

Until now, expedited deportations could only be applied to those detained near the border who had been in the US for less than two weeks.

Rights groups say hundreds of thousands of people could be affected.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) says it will challenge the policy in court.

The new rule is expected to be implemented with immediate effect after it is published on Tuesday.

US immigration policy has come under increasing scrutiny in recent months - in particular, the conditions at the country's detention centres on the southern border with Mexico.

Kevin McAleenan, acting secretary of Homeland Security, said the change was "a necessary response to the ongoing immigration crisis" and would help to relieve the burden on courts and detention centres.

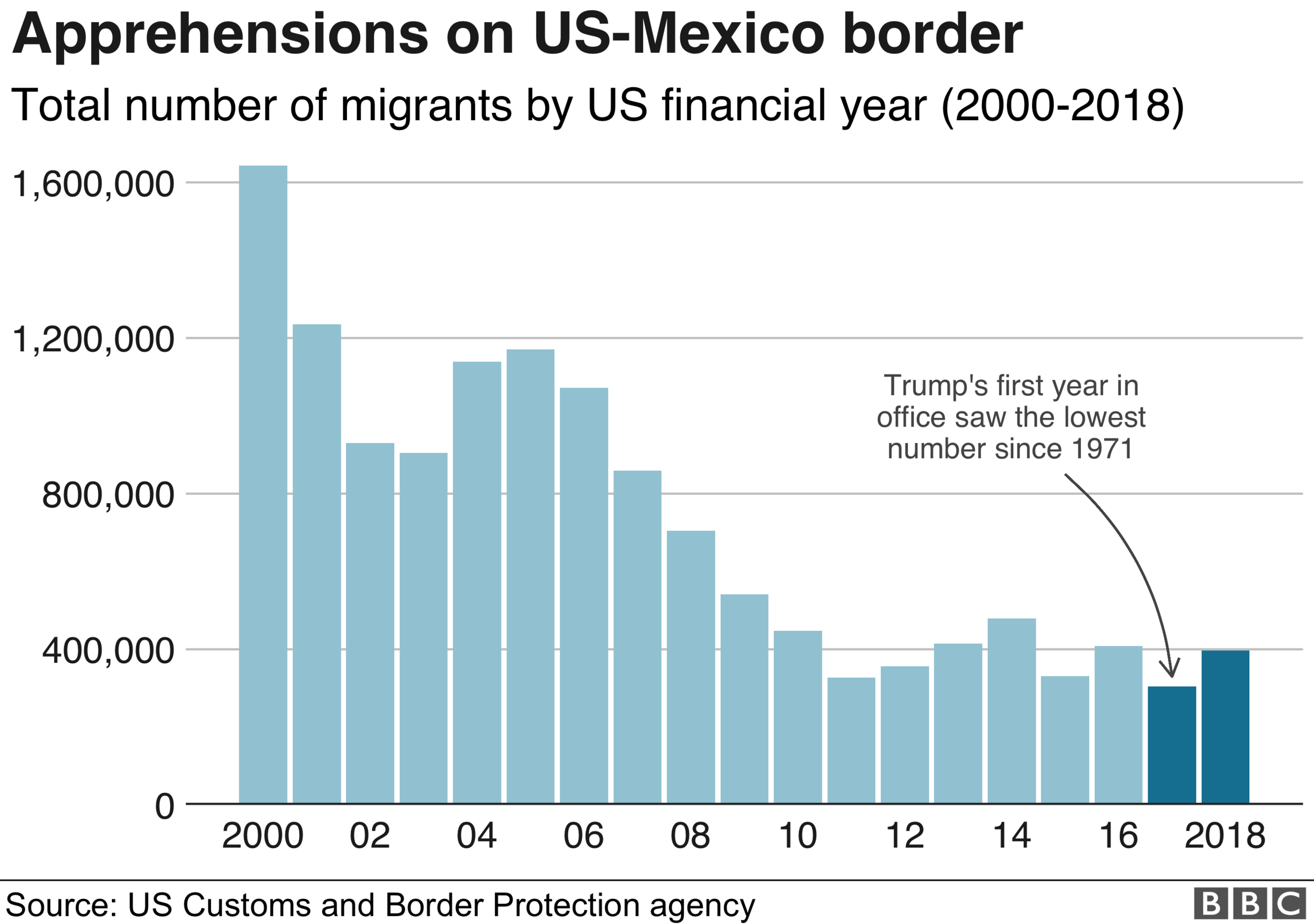

US Border Patrol says it has made 688,375 apprehensions on the south-west border since October 2018, more than double that of the previous fiscal year.

Several analysts predict US President Donald Trump will make hardline immigration control a key element of his re-election campaign in 2020.

What's changing?

Previously, only people detained within 100 miles (160km) of the border who had been in the US for less than two weeks could be deported quickly.

Migrants who were found elsewhere, or who had been in the country for more than two weeks, would need to be processed through the courts and would be entitled to legal representation.

But the new rules state that people can be deported regardless of where in the country they are when they are detained, and without allowing them access to a lawyer.

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said the new rules would allow it to pursue large numbers of illegal migrants more efficiently.

There are 10.5 million undocumented migrants in the US, according to the Pew Research Center

Who is affected?

There are about 10.5 million undocumented immigrants in the US, external, according to the Pew Research Center.

The average undocumented adult immigrant has lived in the country for 15 years, it says.

The DHS has said it could make exceptions for those with serious medical conditions or "substantial connections" to US.

It also says migrants who are eligible for asylum will still be entitled to speak to an asylum officer, who will access their claims.

Earlier this month a Guatemalan mother spoke about the death of her 21-month-old baby daughter in a US detention centre

Muzaffar Chishti, a lawyer from the Migration Policy Institute, says many migrants will struggle to be able to prove how long they have lived in the country when they are put on the spot.

He told CBS News: "When you're apprehended on the street or at a factory, it's obviously not easy to establish with evidence that you've been here for more than two years because you're not carrying all your documents with you."

Who is objecting?

Within hours of the policy being announced on Monday, the ACLU said that it was planning to launch a legal challenge.

"We are suing to quickly stop Trump's efforts to massively expand the expedited removal of immigrants," the rights group tweeted.

"Immigrants that have lived here for years will have less due process rights than people get in traffic court. The plan is unlawful. Period."

Vanita Gupta, president of the Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, told reporters: "The Trump administration is moving forward into converting ICE [Immigration and Customs Enforcement] into a 'show me your papers' militia."

Legal expert Jackie Stevens, a political science professor at Northwestern University, told Reuters that about 1% of the people detained by ICE and 0.5% of those deported were actually US citizens.

"Expedited removal orders are going to make this much worse," she said.

Step into the shoes of a migrant

Maria is fictional. But everything that happens to her here is based on the real experiences of migrants who have travelled to America, experiences that have been documented by rights groups, journalists and lawyers.

See for yourself the decisions and dangers a migrant like Maria may face.

- Published16 July 2019

- Published11 January 2018

- Published2 July 2019

- Published8 July 2019

- Published26 June 2019