Do apostrophes still matter?

- Published

A man who led the war on improper use of apostrophes now admits defeat, saying his grammar vigilante campaign has been brought to an end by a culture of carelessness. So what now?

The battle is over, bad grammar (as in the sign above) has won.

That was the message of retired journalist John Richards, who announced the end of his 18-year campaign to preserve the proper use of the apostrophe last month.

"We have done our best but the ignorance and laziness present in modern times has won," the 96-year-old wrote.

Richards founded The Apostrophe Protection Society in 2001 to defend the "much abused punctuation mark", waging war against advertisements for "ladies fashions", or the much maligned grocer's apostrophe, used to sell apple's and pear's.

"When I first set it up I would get about 40 emails or letters a week from people all over the world," Richards told the BBC. "But then two years ago it started to tail off and nowadays I hardly get anything."

The misuse of an apostrophe can have an outsized impact.

A new holiday in Ghana - Founders' Day - incited heated debate this year over the nation's history, focused squarely on the placement of punctuation.

Whether the country should honour a singular founder (Founder's Day) or a group (Founders' Day) strikes at the heart of Ghana's independence legacy, and hinges on precise use of the apostrophe.

"It can distort truth," says Roslyn Petelin, a writing professor at the University of Queensland, Australia, of a misplaced mark.

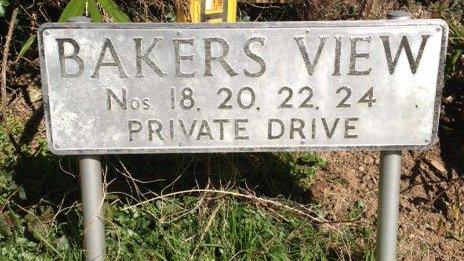

Richards' own pursuit of the apostrophe's proper use saw similar setbacks, with municipalities in the UK, Australia and the US banning apostrophes from street signs - a decision Richards branded "absurd".

So what does Richards' abandoned society say about the state of grammar today? Is he tapping into a wider sense of texting-fuelled grammar apathy?

Maybe not. The demise of The Apostrophe Society itself - an apparent loss to grammarians everywhere - sparked a renewed defence of the punctuation mark.

"It stirred up a real interest in the apostrophe," says Petelin, who says she received "hundreds" of messages on the apostrophe society after its closure, most proclaiming its lasting importance.

The Apostrophe Society reported a 600-fold increase in demand, external after Richards announced its end - exceeding the server's bandwidth and effectively crashing the site, which will reopen in January "for reference and interest".

"It's a quaint idea," Petelin says of the society. "I'd mention it to my students more or less as a joke."

But Petelin, like Richards, is a staunch defender of the apostrophe as "the 27th letter of the alphabet", necessary for clear communication.

"Its correct use avoids bewilderment, confusion, consternation, and irritation to readers who know and love the apostrophe, as I do," she wrote for the Australian Broadcasting Corporation last year.

"I wouldn't call myself an outright pedant, but I do think where it's proper to be correct, one should be," she says.

"There's a certain kind of person who's really interested in apostrophes and commas," Petelin says. "I think it's people who like to defend correctness."

And the apostrophe, perhaps more than any other punctuation mark, has long claimed devoted disciples, including the self-proclaimed Grammar Vigilante of Bristol.

But some grammar experts have a different perspective on a "defence of correctness" - like that taken up by Richards.

"I see no need for an apostrophe society," says Anne Curzan, an English professor and dean of literature, science and arts at the University of Michigan.

"The society works from an idea where there is a stable system that has decayed in recent years," she says. But, "the apostrophe is slippery and has been its entire life in English".

To Curzan, self-styled apostrophe police can have a more harmful impact than simply improving grammar.

"People will sometimes use the judgment of punctuation as a way to judge other people or win an argument," she says, even in disputes about sports or arts - arenas unrelated to grammar.

Meet the 'Grammar Vigilante' of Bristol

The suggestion is that "somehow you're not smart because you misplaced an apostrophe according to standard usage," Curzan says. "It's a total power move."

She adds: "If we're all honest about it - every single one of us have messed up our 'its' and our 'it's'. It's confusing."

Both Curzan and Petelin say the end of The Apostrophe Society is not the end of good grammar.

Even in the age of texting, abbreviations and emojis, young people "are paying very close attention to the details of language", Curzan says.

"Texting is a place where young people have repurposed punctuation," she says. Punctuation in texting - a period at the end of a message or one exclamation mark versus two - carries real weight.

"It's very nuanced."

And both experts agree that the use of the apostrophe - like all punctuation - can be tricky.

"Language is not black and white," Petelin says. "Punctuation is about two-thirds rules, one-third taste."

- Published29 November 2019

- Published12 September 2018

- Published15 March 2013

- Published3 April 2017

- Published11 June 2019

- Published13 May 2013

- Published14 August 2019