US presidents and the fuzzy legality of war

- Published

Trump's critics say the strike against Maj Gen Qassim Suleimani violated international law

President Donald Trump's action and words directed at Iran have led his critics to accuse him of breaking international law. But he's not the first US president to endure this criticism in the theatre of war.

Trump's threat to attack Iran's cultural sites sparked outrage and his officials were quick to deny that option was on the table.

Before that he authorised the killing of Iran's most revered general. According to international law, a government can carry out such a strike if they are acting in self-defence, and US officials said they were trying to prevent attacks.

But Agnes Callamard, UN special rapporteur on extrajudicial killings, disagreed with their assessment. She tweeted that it seemed unlikely that the test for a legal strike, one that is laid out in the UN Charter, was met.

Trump has also championed US military personnel accused of war crimes, calling one of them, Special Operations Chief Edward Gallagher, a "tough guy".

Trump speaks about military personnel and operations in a way that blurs the line on legality.

An attack on a cultural site violates international treaties such as the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property. But he defended his position on targeting cultural sites by saying that enemy commanders used illegal methods and Americans should do the same.

"They're allowed to torture and maim our people," he told reporters. "And we're not allowed to touch their cultural sites? It doesn't work that way."

The 33 Arches bridge in Isfahan was one of those sites in Trump's sights

With his dismissal of international law, he surprised even senior-level US officials. US Defence Secretary Mark Esper said: "I am fully confident that the president, the commander in chief, will not give us an illegal order."

It was another extraordinary moment in the Trump years, showcasing public disputes that he has with his own cabinet secretaries. Trump is not, however, the first president to shock people with his fiery rhetoric or by his use of aggressive military policies. Controversy over these policies has echoed for centuries, and public anger with the presidents themselves has been part of US history.

Long before the 45th president took office, Republican and Democratic leaders were overseeing military and intelligence operations shrouded in secrecy that blurred the lines between lawful and not.

Several of these presidents tussled with a law, the Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF), in their efforts to justify their policies.

The AUMF was designed to allow the use of military force against individuals who helped carry out the 2001 attacks against the US. Since then, presidents have interpreted the law broadly and used it to provide legal justification for military operations in places around the world.

Obama, shown in 2019, defended the legal basis of his secretive drone strikes during his time in office

Barack Obama expanded the use of secretive drone strikes, authorising more than 540 during his time in office.

Human rights advocates said the airstrikes violated international and domestic law, but Mr Obama defended the legal basis for the airstrikes. His advisers argued that because the targeted individuals had been planning attacks against Americans, the airstrikes against them fell within the boundaries of international law.

Over time, the criticism of Obama was muted. The president's use of the airstrikes, says Rutgers' David Greenberg, a presidential historian, was viewed as "a path toward trying to limit the worst brutalities of war".

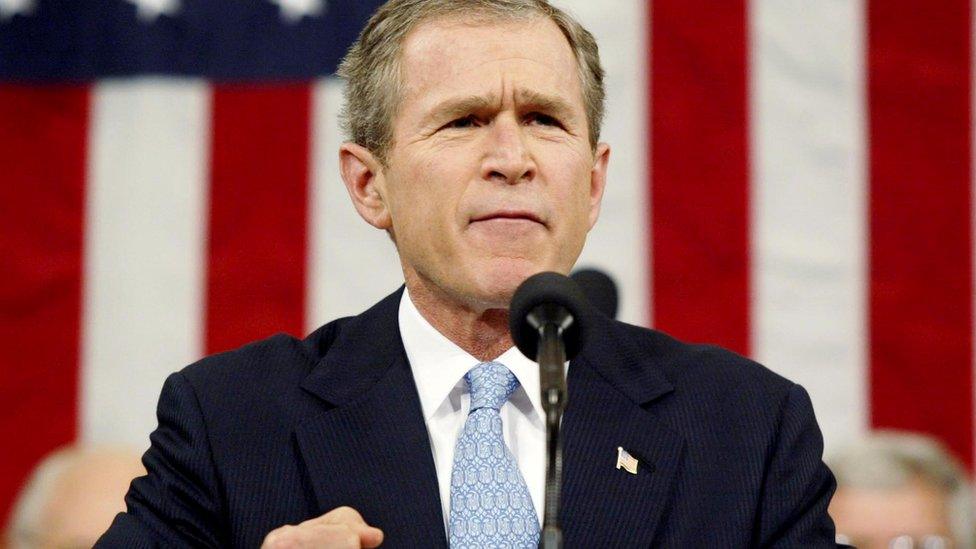

His predecessor, George W Bush, had signed off on only a fraction of airstrikes. Bush pushed boundaries of warfare in another way, however. He authorised the use of so-called enhanced interrogation methods, waterboarding and other tactics widely described as torture. In his case, the harsh policies came to define his time in office. Historian David Greenberg says Bush will be remembered for the Iraq war and the torture: "He's paid a price."

Bush defended the use of waterboarding and other tactics during interrogations

Before that, President Bill Clinton "embraced" extrajudicial renditions, the transporting of terrorism suspects to a country where prisoners are tortures, say legal scholars.

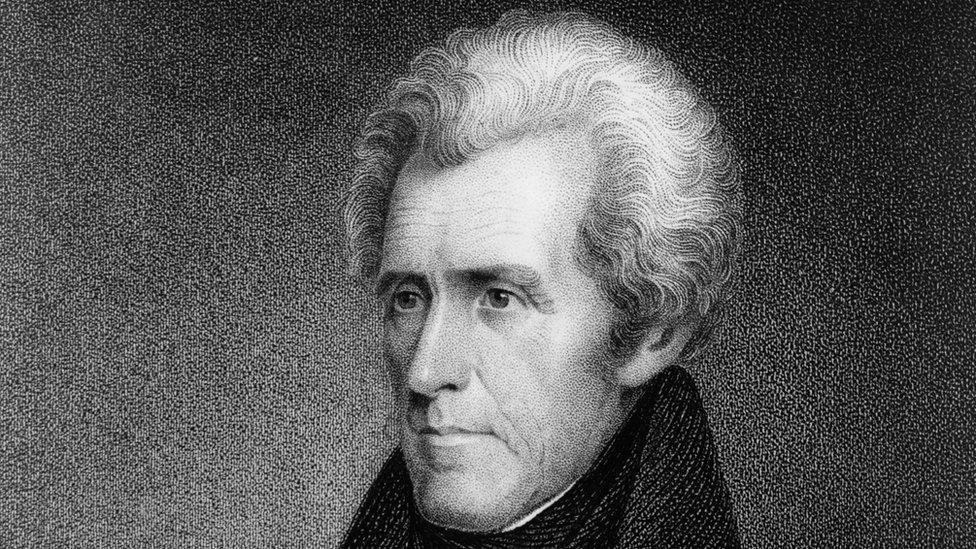

Clinton and the other presidents attempted to provide legal justification for their policies. Decades earlier, Andrew Jackson, who served as president in the early 1800s, had done the same. He signed the Indian Removal Act, and through this law forced Native Americans off land. People said that their forced removal was "barbaric", says Greenberg, but there was at least a pretext of abiding by norms.

President Trump does not feel the need to frame his policies in such a way, says the historian. "You don't just willy-nilly bomb cultural sites, but he kind of revels in the flouting of norms."

Part of his appeal is the way that he provokes those who hold more liberal notions of international law, he adds.

Critics of Andrew Jackson described his policies towards Native Americans as "barbaric"

Trump's supporters say that despite his rhetoric he has been more disciplined in his rollout of military policies than previous presidents.

James Carafano, an analyst at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think-tank in Washington, says Trump has been cautious in what he has actually done with the military - the most conservative and the most restrained.

Some analysts say the real problem is that presidents are granted too much power, and they take things too far.

"They used their authority to carry out acts that we view as illegal, immoral, unethical - you pick the word," says Andrew Bacevich, the president of a foreign-policy think-tank, Quincy Institute. "The problem is not Trump - but that we have invested the presidency with authority far in excess of what should be allowed."

As Bacevich points out, presidents throughout the ages have pushed the boundaries of the law. The question now is - what's next?