Five reasons why Canada's 'shutdown' is a big deal

- Published

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is under pressure from all sides.

At the forefront is a conflict first sparked over indigenous opposition to a natural gas pipeline project, that has now evolved to include broader complex issues like indigenous governance and indigenous rights.

It has led to rail blockades and protests that have crippled rail lines and disrupted the flow of the country's economy.

Those events have underscored a pressure point for Mr Trudeau - he has struggled to deliver on his promise to chart a path for Canada that balances oil and gas development, environmental stewardship and indigenous reconciliation.

Here are five reasons why the current unrest is a big deal.

1 - It's bad news for Justin Trudeau

The conflict has forced work to be paused on a major natural gas pipeline, the Coastal GasLink project, that Mr Trudeau's Liberal government supports.

Until this week, his ministers had a hard time trying to set up a meeting with the Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs who led the calls for protests in support of their cause.

It is the latest resource project to hit gridlock amid opposition by some First Nations and environmental campaigners.

Justin Trudeau's leadership has been called into question

The prime minister's political opponents have seized on the crisis to argue that he has shown weak leadership in his handling of the rail blockades and upholding of the rule of law.

They are also laying the blame for the country's struggling oil and gas sector at his feet.

And Canadians are feeling frustrated - a poll published this week by the National Post newspaper, external suggested that almost 60% of Canadians don't think the country is headed in the right direction, while 63% of respondents said Mr Trudeau was "not governing well".

Three areas - resource development, environmental stewardship and indigenous rights - have become more challenging for countries like Canada as climate change becomes a greater public concern and indigenous communities are increasingly empowered, says former interim Liberal leader Bob Rae.

Says Mr Rae: "Where governments and companies are prepared to embrace the need for dialogue and inclusion and recognition and so on, projects proceed and in fact benefit the First Nations quite significantly in terms of economic development".

"Frankly nothing else works."

2 - Businesses are hit by crippled rail troubles - and farms are getting cold

Rail blockades have meant that parts of the cross-country rail system have ground to a halt over the past weeks as the current conflict drags on.

Almost 1,500 rail workers are temporarily out of work and many industries are struggling with the impact, including agriculture.

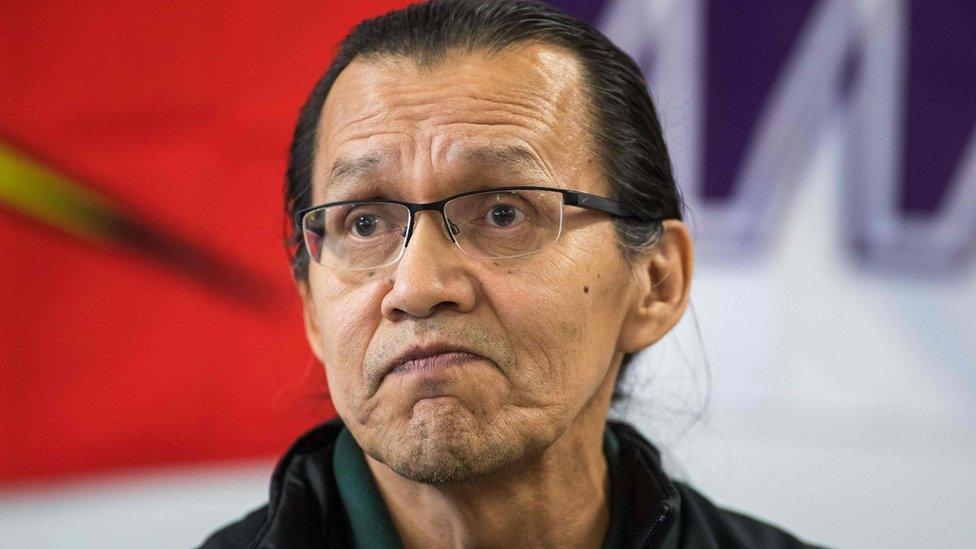

Wet'suweten hereditary chief Frank Alec said they were open to talks based on some conditions

Quebec dairy and grain farmer Martin Caron says farmers are under "real stress" amid shortages of soy and propane used for food and heating.

About 80% of the province's propane and 65% of its soy is transported by rail, he says. Some is now being shipped by trucks at a significant mark-up.

Propane is used to heat buildings holding livestock, critical in Canadian winters.

"[There is] stress because we have animals and if we can no longer heat them properly, we put them at risk," says Mr Caron. "So there's an economic stress but also a mental health aspect to this - the animals are part of our families. The producers don't want to put the animals at risk."

While rail blockades have subsided this week and the Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs have sat down with government officials, it will take a number of weeks before the rail system is fully up and running.

A train halted near a key blockade that stopped rail transport across the country

"People are hoping with all their hearts that the federal government, among others, will position itself quickly to prevent crises like this," says Mr Caron.

3 - Companies are spooked by the uncertainty

The University of Calgary's Harrie Vredenburg, an expert on the global energy industry, says Canada has traditionally been a low risk political environment for investment. This helped it become the world's fourth largest oil and gas exporter.

But the lack of certainty around the regulatory and approval process is now chilling business interest in the sector, he says.

A company can spend years getting environmental and First Nations approvals.

"In Canada you do all that and at the end it's still a political decision that depends on what activists are doing and what the media is saying and it's a totally unpredictable outcome," says Mr Vredenburg.

This month, mining company Teck Resources pulled its application to build a major oil sands mine in northeastern Alberta.

Teck Resources recently pulled its application for a major mining project in Alberta

The firm said the global capital markets, investors and customers are looking to places that reconcile "resource development and climate change".

"This does not yet exist here today and, unfortunately, the growing debate around this issue has placed [the project] and our company squarely at the nexus of much broader issues that need to be resolved."

The decision also came amid questions about the project's financial viability.

"It had become a political football and I think in the end, the Teck board and management just said it isn't worth it," says Mr Vredenburg.

4 - It adds to the sense of 'western alienation'

The economic recovery in the province of Alberta, after an overabundance of supply caused the worldwide price of oil to plummet a few years ago, has been slow.

The oil woes led to the loss of more than 100,000 jobs in Alberta and a full-on recession.

Mohawk protesters in Ontario have been strong supporters of the Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs

In October's general election, the resource-rich provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan turned solidly away from Mr Trudeau's Liberal party amid a sense in western Canada that its interests were not represented.

Several pipeline projects - seen by the industry as critical for gaining access to global markets - hang in limbo, fuelling more frustration.

Some provincial premiers are also at loggerheads with Mr Trudeau over his main climate initiative, a carbon tax, which will be challenged in the country's top court.

The Teck decision and the Wet'suwet'en conflict have only ramped up tensions.

Mr Vredenburg says "constant bickering" between provincial and federal leaders over energy and climate "doesn't help Canada's brand".

5 - It highlights the challenges facing indigenous reconciliation and rights

Mr Trudeau came to power promising to transform the country's relationship with indigenous people.

This conflict has highlighted the challenges involved in moving forward with that reconciliation.

Karen Joseph, CEO of the charity Reconciliation Canada, says the country is at the "very early stages of this process of reconciliation" with many systemic challenges that reinforce inequality still in place.

She says amid the unrest everybody needs "to stop and think about how we can do better, how we can show our children how we resolve conflict as leaders and as peoples so that they can move forward".

Canada has a duty to consult with indigenous peoples before they begin any projects on their land.

But there is ambiguity around the rules for consultation - one of the roots of the civil unrest seen in recent weeks.

There have been occasional confrontations during the protests

Coastal GasLink received the support of 20 First Nations along its route, including some Wet'suwet'en and their band council, though not a number of Wet'suwet'en hereditary chiefs.

Some First Nations have been vocal opponents of major resource projects.

Other indigenous communities have chosen to participate in the oil and gas sectors, seeing agreements with resource firms as an opportunity to close the gap in living standards that exists between indigenous peoples and the rest of Canada.

In a recent op-ed in the Globe and Mail newspaper,, external Abel Bosum, Grand Chief of the Grand Council of the Crees of Northern Quebec, shared how his community and the province were able to come to the table after a bitter conflict over large-scale resource development, and found a beneficial path forward.

Canada is not alone in facing many of these challenges that need a "significant shift" in how countries look at issues raised by the Wet'suwet'en conflict, says Ms Joseph.

"The difference in Canada is we have a opportunity and a number of policies that can facilitate a new way forward that's potentially shareable globally."

- Published25 February 2020

- Published2 October 2018