Coronavirus: What this crisis reveals about US - and its president

- Published

The usually packed Times Square is empty

There are no fresh flowers at the 9/11 Memorial any more. An American altar usually decorated with roses, carnations and postcard-sized Stars and Stripes is sequestered behind a makeshift plastic railing. Broadway, the "Great White Way", is dark. The subway system is a ghost train. Staten Island ferries keep cutting through the choppy waters of New York harbour, passing Lady Liberty on the way in and out of Lower Manhattan, but hardly any passengers are on board. Times Square, normally such a roiling mass, is almost devoid of people.

In the midst of this planetary pandemic, nobody wants to meet any more at the "Crossroads of the World". A city known for its infectious energy, a city that likes to boast it never even has to sleep, has been forced into hibernation. With more cases than any other American conurbation, this city is once again Ground Zero, a term no New Yorker ever wanted applied here again. With manic suddenness, our world has been turned upside down, just as it was on September 11th.

Nations, like individuals, reveal themselves at times of crisis. In emergencies of this immense magnitude, it soon becomes evident whether a sitting president is equal to the moment. So what have we learnt about the United States as it confronts this national and global catastrophe? Will lawmakers on Capitol Hill, who have been in a form of legislative lockdown for years now, a paralysis borne of partisanship, rise to the challenge? And what of the man who now sits behind the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office, who has cloaked himself in the mantle of "wartime president"?

Of the three questions, the last one is the least interesting, largely because Donald Trump's response has been so predictable. He has not changed. He has not grown. He has not admitted errors. He has shown little humility.

Instead, his critics say, all the hallmarks of his presidency have been on agitated display: his boasts - he has awarded himself a 10 out of 10 for his handling of the crisis. The politicisation of what should be the apolitical - he toured the Centers for Disease Control wearing a campaign cap emblazoned with the slogan "Keep America Great".

His truth-twisting: he now claims to have fully appreciated the scale of the pandemic early on, despite dismissing and downplaying the threat for weeks. His attacks on the "fake news" media, including a personal assault on a White House reporter who asked what was his message to frightened Americans: "I tell them you are a terrible reporter." His mocking of Senator Mitt Romney, the only Republican who voted at the end of the impeachment trial for his removal from office, for going into isolation.

"Every one of these doctors said: 'How do you know so much about this?'"

His continued attacks on government institutions in the forefront of confronting the crisis - "the Deep State Department" is how he described the State Department from his presidential podium the morning after it issued its most extreme travel advisory urging Americans to refrain from all international travel. His obsession with ratings, or in this instance, confirmed case numbers - he stopped a cruise ship docking on the West Coast, noting: "I like the numbers where they are. I don't need to have the numbers double because of one ship that wasn't our fault." His compulsion for hype - declaring the combination of hydroxycholoroquine and azithromycin "one of the biggest game-changers in the history of medicine," even as medical officials warn against offering false hope.

His lack of empathy. Rather than soothing words for relatives of those who have died, or words of encouragement and appreciation for those in the medical trenches, Trump's daily White House briefings commonly start with a shower of self-congratulation. After Trump has spoken, Mike Pence, his loyal deputy, usually delivers a paean of praise to the president.

His appeal to xenophobia that has always been the sine qua non of his political business model - repeatedly he describes the disease as the "Chinese virus". Just as he scapegoated China and Mexican immigrants for decimating America's industrial heartland ahead of the 2016 presidential election, he is blaming Beijing for the coronavirus outbreak in an attempt to win re-election.

My judgement is that his attempt at economic stewardship has been more convincing than his mastery of public health. A lesson from financial shocks of the past, most notably the meltdown in 2008, is to "go big" early on. That he has tried to do. But here, as well, there are shades of his showman self. He seems to have rounded on the initial figure of a trillion dollars for the stimulus package because it sounds like such a gargantuan number - a fiscal eighth wonder of the world.

Trump favours simple solutions to complex problems. He closed America's border to those who had travelled to China, a sensible move in hindsight. However, the coronavirus outbreak has required the kind of multi-pronged approach and long-term thinking that seems beyond him. This has always been a presidency of the here and now. It is not well equipped to deal with a public health and economic emergency that will dominate the rest of his presidency, whether he only gets to spend the next 10 months in the White House or another five years.

The Trump presidency has so often been about creating favourable optics even in the absence of real progress - his nuclear summitry with the North Korean despot Kim Jong-un offers a case in point. But such tactics do not work as well in a national emergency.

What have we learnt of the United States? First of all, we have seen the enduring goodness of this country.

As with 9/11, we have marvelled at the selflessness and bravery of its first responders - the nurses, doctors, medical support staff and ambulance drivers who have turned up to the work with the same sense of public spiritedness shown by the firefighters who rushed towards the flaming Twin Towers. We've witnessed the ingenuity and creativity of schools that have transitioned to remote, online teaching without missing a beat. We've seen a can-do spirit that has kept stores open, shelves stocked and food being delivered. In other words, most Americans have shown precisely the same virtues we have seen in every country brought to a halt by the virus.

As for the American exceptionalism on display, much of it has been of the negative kind that makes it hard not to put head in hands. The lines outside gun stores. The spike in online sales of firearms - Ammo.com has seen a 70% increase in sales. The panic buying of AR-15s. Some Christian fundamentalists have rejected the epidemiology of this pandemic. To prove there was no virus, a pastor in Arkansas boasted his parishioners were prepared to lick the floor of his church.

Once again, those who live in developed nations have been left to ponder why the world's richest country does not have a system of universal healthcare. Ten years after the passage of Obamacare, more than 26 million Americans do not have health insurance.

Rather than a coming together, the crisis has demonstrated how for decades Americans have conducted a political version of social distancing: the herd-like clustering of conservatives and liberals into like-minded communities caused by the allergic reaction to compatriots holding opposing political views. Once again, we have seen the familiar two Americas divide, the usual knee-jerk tribalism. Republicans have been twice as likely as Democrats to view coronavirus coverage as exaggerated. Three-quarters of Republicans say they trust the information coming from the president, whereas the figure among Democrats is just 8%.

As the Reverend Josh King told the Washington Post despairingly: "In your more politically conservative regions, closing is not interpreted as caring for you. It's interpreted as liberalism." Even on 13 March, when the CDC projected that up to 214 millions could be infected, Sean Davis, the co-founder of the right-wing website, The Federalist, tweeted: "Corporate political media hate you, they hate the country, and they will stop at nothing to reclaim power to rule over you. If that means destroying the economy via a panic they helped incite, all while running interference for the communist country that started it, so be it."

The latest Gallup polling shows the split: 94% of Republicans approve of his handling of the crisis, compared with 27% of Democrats. But overall, six out of ten Americans approve, pushing his approval rating up again to 49%, matching the highest score of his presidency. As with previous crises, such as 9/11, Americans tend to rally around the presidency, although Donald Trump remains a deeply polarising figure. After the attacks of September 11th, George W Bush's approval rating was over 90.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

AVOIDING CONTACT: Should I self-isolate?

VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

The political geography of America, with its red and blue state separatism, has even affected how voters are being physically exposed to the virus. Democrats tend to congregate in the cities, whose dense populations have made them hotspots. Republicans tend to live in more sparsely populated rural areas, which so far have not been so badly hit. Thus, the polarisation continues amidst the pandemic.

Rather than to the Trump White House, much of "Blue America" has looked for leadership to its state capitals: Democratic governors such as Andrew Cuomo in New York (who Trump tweeted should "do more"), Gavin Newsom in California (whom Trump has praised) and Jay Inslee in Washington state (whom the president called a "snake" during his visit to the CDC).

For American liberals, Dr Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has become the subversive hero of the hour. Offering an antidote to this post-truth presidency, Fauci sticks to scientific facts. After repeatedly contradicting Donald Trump over the seriousness of the outbreak, he is on his way to being viewed with the same affection and reverence as the liberal Supreme Court jurist Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Fauci has become a phenomenon on social media

Surely the coronavirus outbreak will eventually lead to an end momentarily to the gridlock on Capitol Hill. Legislators have no other choice but to legislate given the enormity of the economic crisis and the spectre of a 21st Century Great Depression.

However, the first two attempts to pass a stimulus package failed amidst the usual partisan acrimony and brinksmanship. Republicans and Democrats are arguing over whether to include expansions of paid leave and unemployment benefits, and what the Democrats are calling a slush fund for corporate America that could be open to abuse. Once again, Capitol Hill's dysfunction has been shown to be both systemic and endemic.

Given the scale of the public health and economic crisis, the hope would be of a return to the patriotic bipartisanship that prevailed during much of the Fifties and early Sixties, which produced some of the major post-war reforms such as the construction of the interstate highway system and the landmark civil rights acts. History, after all, shows that US politicians co-operate most effectively in the face of a common enemy, whether it was the Soviet Union during the Cold War or al-Qaeda in the initial months after 9/11.

60 days of coronavirus in the US - in 60 seconds

But the early response of lawmakers on Capitol Hill is far from encouraging. And if there is cross-party co-operation - as there will surely be in the end - it will not be the product of patriotic bipartisanship but rather freak-out bipartisanship, the legislative equivalent of panic buying.

The paradox here, as lawmakers face-off, is that crises erase philosophical lines. As in 2008, ideological conservatives have overnight become operational liberals. Those who ordinarily detest government have come in this emergency to depend on it. Corporate America, which is generally phobic towards federal intervention, is now desperate for government bailouts.

Trickle-down supply siders have become Keynesian big spenders, such is their desire for government stimulus spending funded by the taxpayer. Even universal basic income, a fringe idea popularised by the Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang, has gone mainstream. The US government intends to give $1,200 payments to every American.

In this call to national action, we have been reminded of how the federal government has been run down over the past 40 years partly because of an anti-government onslaught that started with Ronald Reagan. In 2018, the team responsible for pandemic response on the National Security Council at the White House was disbanded. The failure to carry out adequate testing, the key to containing outbreaks early on, is linked to a funding shortfall at the Department of Health and Human Services.

As with the attacks of 11 September 2001, warnings within government were repeatedly ignored. In recent years, there have been numerous exercises to test the country's preparedness for a pandemic - one of which involved a respiratory virus originating from China - that identified exactly the areas of vulnerability now being exposed. As with Hurricane Katrina, the Federal Emergency Management Agency has struggled. As ever, there are tensions between federal agencies and the states. The institutional decline of government that led so many Americans to pin their faith in an individual, Donald Trump, is again plain to see, whether in the shortage of masks and protective gowns or the dearth of early testing.

Consequently, America's claim to global pre-eminence looks less convincing by the day. While in previous crises, the world's most powerful superpower might have mobilised a global response, nobody expects that of the United States anymore. The neo-isolationism of three years of America Firstism has created a geopolitical form of social distancing, and this crisis has reminded us of the oceanic divide that has opened up even with Washington's closest allies. Take the European travel ban, which Trump announced during his Oval Office address to the nation without warning the countries affected. The European Union complained, in an unusually robust public statement, the decision was "taken unilaterally and without consultation".

Nor has the United States offered a model for how to deal with this crisis. South Korea, with its massive testing programme, and Japan have been exemplars. China, too, has shown the advantages of its authoritarianism system in enforcing a strict lockdown, which is especially worrying when the western liberal order looks so wobbly. Hopefully, nobody will forget how officials in China tried to cover up the virus for weeks and silenced whistleblowers, showing the country's ugly autocratic side even as the outbreak was spreading. But whereas Beijing managed to build a new hospital in just 10 days, the Pentagon will take weeks to move a naval hospital ship from its port in Virginia to New York harbour.

Aerial time-lapse shows Wuhan hospital construction

Politically, there will be so many ramifications. It is worth remembering, for example, that the Tea Party was as much a reaction to what was called the "big government conservatism" of George W Bush in response to the financial crisis as it was to the pigmentation of Barack Obama. The official history of the Tea Party movement states it came into existence on 3 October, 2008, when Bush signed into law TARP, the Troubled Asset Relief Programme which saved the failing banks. Tea-Partiers viewed that as an unacceptable encroachment of government power.

Likewise, it is worth bearing in mind that the two major convulsions of the 21st Century, the destruction of the Twin Towers and the collapse of Lehman Brothers, both ended up having a polarising effect on US politics. The fragile bipartisan 9/11 consensus was shattered by the Bush administration's decision to invade Iraq. The financial crisis fuelled the rise of the Tea Party and further radicalised the Republican Party.

What will be the impact on the presidential election? Judging by the Lazarus-like revival of Joe Biden, the signs are that Democrats are voting for normal. Clearly, a significant majority is not in the mood for the political revolution promised by Bernie Sanders. A 78-year-old whose candidacy was almost derailed in its early stages because he was so tactile looks again like a strong candidate in these socially distant times.

The view from Lincoln Memorial across the National Mall in Washington, DC

Many Americans are yearning for precisely the kind of empathy and personal warmth that Biden offers. Even before the coronavirus took hold, he had made recovery his theme, a narrative in accord with his life story. Many also want a presidency they could have on in the background. A less histrionic figure in the Oval Office. Soft jazz rather than heavy metal. A return to some kind of normalcy. But who would make any predictions? Only a few weeks ago, when the chaos of the Iowa caucuses seemed like a major story, we were prophesying Biden's political demise.

Besides, normalcy is not something we can expect to see for months, maybe even for years. Rather, the coronavirus could dramatically reshape American politics, much like the other massive historical convulsions of the past 100 years.

The Great Depression led to the New Deal, and its massive extension of federal power, through welfare programmes such as Social Security. It also made the Democrats, the champions of government, politically dominant. From 1932 onwards, the party won five consecutive presidential elections. World War II, among other social changes, gave impetus to the struggle for black equality, as African-American infantrymen who fought fascism on the same battlefields as white GIs demanded the same menu of civil rights on their return home. The attacks of 11 September made many Americans more wary of mass immigration and religious pluralism. The Great Recession undermined faith in the American Dream.

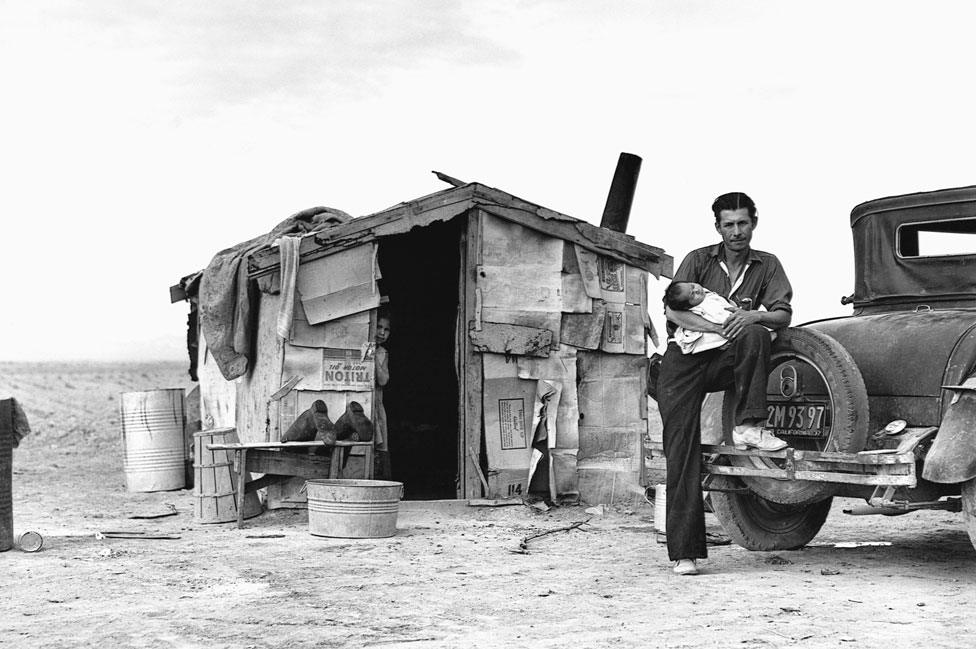

A migrant worker in California in 1937

How America changes as a result of coronavirus will be determined by how America responds.

Liberals may be hoping the outbreak will highlight the need for universal healthcare, a New Deal-style revival of government, the return of a more fact-based polity and a stronger response to global warming, another planetary crisis which has the potential to paralyse and overwhelm so much of the world.

Conservatives may conclude the private sector rather than government is better equipped to deal with crises, amplifying their anti-government rhetoric, that gun controls should be further relaxed so that Americans can better protect themselves, and that individual liberties should not be constrained by nanny states.

Every day on my way to work, I pass the 9/11 memorial where the Twin Towers once stood, and watch people laying their flowers and muttering their quiet prayers. Many is the time I have wondered whether I would ever cover a more world-altering event. As I look out of my window on a quiet and eerie city that feels more like Gotham than New York, I fear we may be confronting it now.

You can follow Nick on Twitter, external

Correction 6 August 2020: This article has been amended following a complaint to the BBC's Executive Complaints Unit.