Coronavirus response: Things the US has got right - and got wrong

- Published

What Trump voters think of his handling of the virus outbreak

It's been two months since the US declared a national emergency over the coronavirus outbreak. The death toll from Covid-19 now stands at more than 83,000 - and tens of millions of Americans are out of work.

There has been a robust ongoing debate over whether the US was adequately prepared for a pandemic and if the proper steps were taken as the virus began to appear on American soil.

Ever since mid-March, however, most government officials have acknowledged that the magnitude of the crisis required a response of enormous scope.

The unprecedented lockdowns imposed in much of the country were designed to slow the spread of the virus, prevent the nation's healthcare system from being overwhelmed, buy time for further preparations and protect Americans particularly at-risk of serious health complications.

This is how some of those efforts have succeeded - and failed.

SUCCESSES

A flattened curve - somewhat

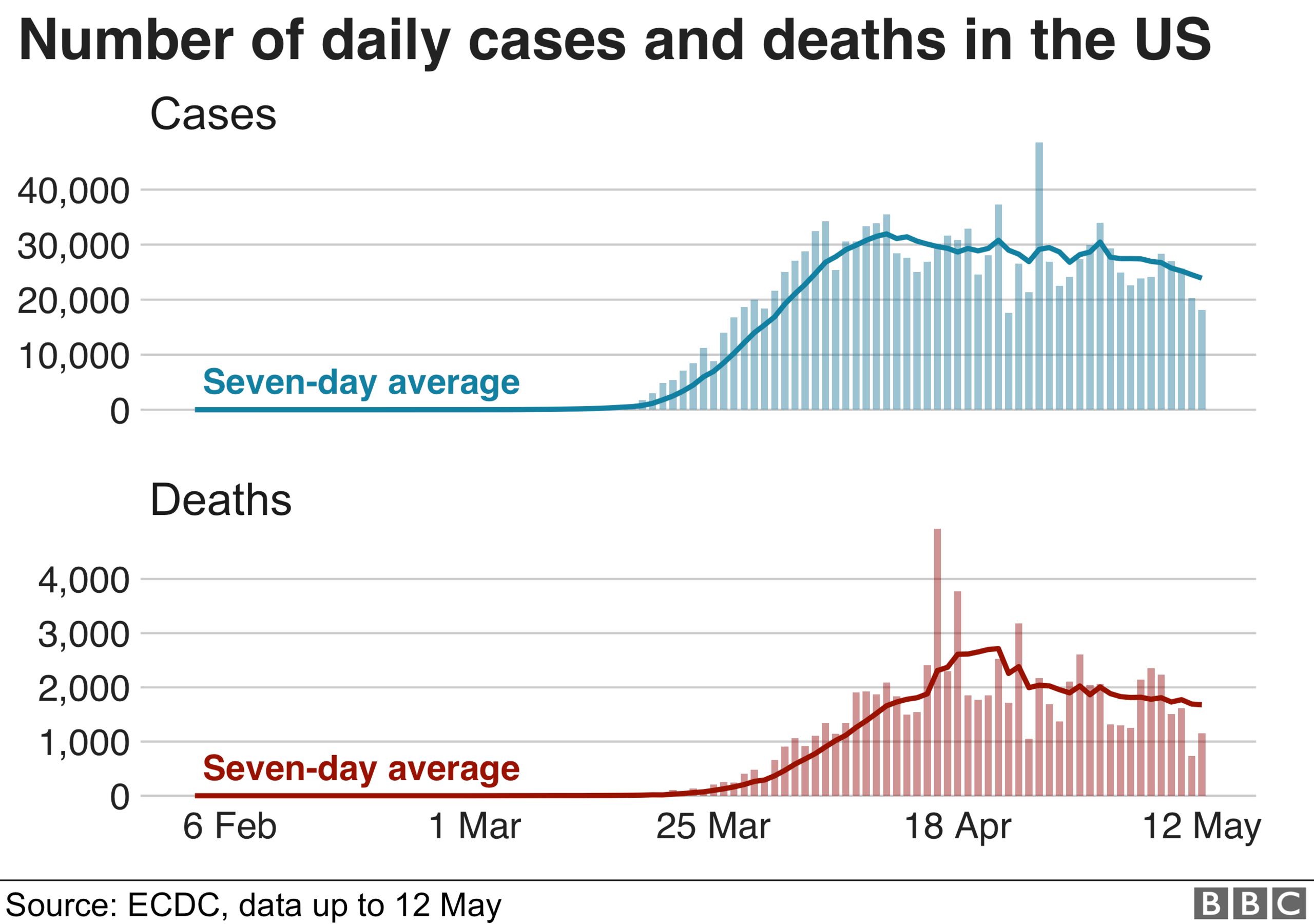

First, the good news. The patchwork of shutdowns and social-distancing across almost every US state has succeeded in stopping the exponential spread of the virus. In hard-hit states like New York, Michigan and Louisiana, the pandemic's growth curve has bent downward. What was once a runaway crisis in these hotspots has been controlled.

Some states, including hard-hit New York have managed to slow the spread of the virus

Next, the concerning news. Outside of those three states, the rest of the US has continued to see an overall rise in the infection rates, albeit not nearly as sharply as before. Taken together, the chart of new cases in the US seems to have reached a plateau, but perhaps not a stable one.

And now some bad news. According to the Washington Post, states that have begun a partial reopening have seen their number of cases increase the most compared to those that have kept them in place. And an unreleased Coronavirus task force report leaked to NBC News, external indicates that cities in the interior of the US, including Des Moines, Nashville and Amarillo, all recently have seen more than 70% week-over-week increases in cases.

So while the efforts at restricting movement and business have been one of the success stories of the past six weeks, this success could be short-lived if it's not followed by a rigorous testing programme that includes extensive contact-tracing for those found to be infected.

"I think we're going in the right direction, but the right direction does not mean we have by any means total control of this outbreak," Dr Anthony Fauci, head of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and a White House Coronavirus Task Force member, said in Senate testimony on Tuesday.

Ventilator surplus

When asked to cite an administration accomplishment in its handling of the coronavirus pandemic, White House Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany pointed to ventilators - the medical devices used to help patients breathe when they can no longer do so on their own.

"The success story is that this administration mobilised the greatest efforts since WW2, that we provided something like 4,000 ventilators to New York," she said. "Not a single American died in this country for lack of a ventilator."

The US government spent several billion dollars on contracts for new ventilators, and the president used a 70-year-old law, the Defense Production Act, to prod auto manufacturer General Motors to switch to ventilator production and streamline supply-chain issues for other manufacturers.

In the end, the ventilator crunch never materialised - because of increased supply, low-use states sharing their stockpiles, lower demand and a shifting view by healthcare professionals of the machine's benefits given the low survival rate of those who used them.

"I think they were able to share the ventilators from places that didn't need them to places that did need them quite effectively," says Gerard Anderson, a professor of health policy at Johns Hopkins University's Bloomberg School of Public Health. "There have been no place that I'm aware of that have had a severe ventilator shortage."

In a 25 April tweet, Trump called the US "the king of ventilators", external and has since offered to ship surplus machines to countries in Latin America, Europe and Africa, affirming that the ventilator supply is now a source of pride for the administration.

Hospital capacity

On 18 March, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo issued a dire warning. Within 45 days, New York City would need 110,000 hospital beds to treat those suffering from the coronavirus, and it only had 53,000 available.

Donald Trump subsequently dispatched the hospital ship Comfort to New York to increase the city's capacity, and the state converted the Javitz Center - the site of Hillary Clinton's 2016 election-night party-turned-wake - into a 2,000-bed medical facility.

In the end, New York hit a peak for hospitalisations on 12 April at 18,825 - well below the worst-case scenarios. The numbers have been in decline ever since.

NYC nurse: ‘I just had a baby - now I’m going to the frontline.’

Across the US, the healthcare system has been strained in some states, such as New Jersey, Maryland and Massachusetts, but it has held up to the increased demand.

"In a clinical sense, it was a tremendous success," says Anderson. "They were able to handle all the patients that arrived. They might have had to wait, but all the patients that needed intensive care tended to get intensive care."

The dire warnings of medical triage akin to what took place in northern Italy failed to come to pass - at least for now.

Vaccines and treatments

Multiple vaccines for the coronavirus have already begun clinical trials on humans. According to the World Health Organization, there are more than 100 possible vaccines in various stages of development around the world.

Original predictions were that it could be more than a year and a half before one was proven effective and ready to use. Now the hoped-for date is sometime in the beginning of 2021.

"From a vaccine development, we are doing incredibly well in that we've got a large number of entities trying to develop the vaccine," says Anderson. "The concern is, do we take that first one that is available, or wait for something that is probably better?"

Multiple potential coronavirus vaccines are in clinical trials

Until a vaccine is developed and widely distributed, the best-case scenario for governments contemplating how to respond to the pandemic will be to limit its spread and protect those most vulnerable. Life in the US - and across the world - will not be able to return fully to some semblance of normalcy until that day is reached. Fortunately, it seems, progress is being made.

Meanwhile, the antiviral drug Remdesivir has been found to shorten the average hospital stays of coronavirus patients from 15 days to 11.

"Although a 31% improvement doesn't seem like a knockout 100%, it is a very important proof of concept," Anthony Fauci, head of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said last week. "What it has proven is that a drug can block this virus." It's the first therapeutic drug to have documented evidence of effectiveness.

MISTAKES

Overhyped treatments

For weeks, Trump - echoed by many prominent conservative commentators - touted the potential medical benefits of the anti-malarial drug chloroquine.

Some healthcare facilities and providers rushed to stock up on supplies, leading to widespread shortages. In one nursing home in Texas, patients were administered the drug without family consent, as county public-health officials raced to try to head off an outbreak in their jurisdiction.

Further studies have since indicated that the drug is ineffective at best, however, and could lead to life-threatening complications for some who used it.

"You have to rely on the science," says Anderson. "Pushing things too quickly into the market sphere in an emergency situation can be very dangerous."

Doctors dismantle Trump's treatment comments

During a press conference in April, the president speculated about the use of disinfectants or ultraviolet radiation to kill the coronavirus inside infected humans. The president was widely criticised - and mocked - for his off-the-cuff remarks, as some states reported an increase in calls to poison-hotline numbers.

While scientists and public health officials have had a prominent role on the White House's coronavirus task force, the president has occasionally veered away from their guidance to offer his own armchair medical opinions. When those views have translated into government action, or led to life-threatening behaviour, they have made the implementation of science-based policy more difficult.

Lack of PPE production/supply

When a nurse visiting the White House last week told the president that supplies of personal protective equipment (PPEs) like gloves, facemasks and gowns have been "sporadic but manageable", the president replied: "Sporadic for you, but not sporadic for a lot of other people".

For months, however, there have been widespread reports of healthcare workers having to make do without the proper protective clothing or forced to reuse existing supplies. Many Americans outside the medical profession have resorted to fashioning make-shift masks from scarves and coffee filters, as protective items are even harder for them to find.

The shortage in protective gear has been caused, in part, by virus-related disruptions in the supply chain from manufacturers in China, says Anderson. Administration efforts to ramp-up domestic production have had mixed results. A US national stockpile, not designed for such a widespread pandemic, was quickly depleted.

Trump initially told states it was primarily their responsibility to acquire the needed supplies, quipping that the federal government was "not a shipping clerk". That left many states bidding against each other on the open market for protective gear and, on occasion, facing federal government seizure of shipments they had ordered for themselves.

"Project Airbridge", a recently ended administration programme to subsidise air shipment of protective supplies from overseas manufacturers, had little transparency. The government boasted that more than a million items were shipped, but a Washington Post investigation found little evidence of where the supplies ended up., external

While domestic production of protective gear has increased in recent weeks, there are still concerns that the distribution network is uneven and needed supplies aren't reaching front-line healthcare workers quickly enough.

Testing shortcomings

On Monday afternoon, Trump stood in the Rose Garden in front of banners declaring "America leads the world on testing" and told the gathered reporters that "we have met the moment, and we have prevailed".

He touted the $11bn the federal government would be giving to states to ramp up their testing programmes, and the 9 million coronavirus tests that have been given in the US so far, including a current rate of more than 300,000 a day.

US President Donald Trump has touted US testing capacity

Although he boasted that the US now surpassed South Korea, long held up as an exemplar of coronavirus response, in per-capita testing, the cold reality is that the Koreans ramped up their testing in February and March. The US may have caught up, but by now the virus has claimed more than 80,000 victims and spread across the nation.

"We treaded water during February and March," Republican Senator Mitt Romney said during a Senate coronavirus hearing on Tuesday. "I find our testing record nothing to celebrate whatsoever."

The administration's case has been complicated by a pattern of overpromising on testing - only to come up short. On 10 March, Vice-President Mike Pence promised that the US would hit 4 million coronavirus tests a week. That number wasn't achieved until the end of April. (Pence says he was talking about tests distributed, not processed).

In mid-March, Trump touted a public-private partnership to offer drive-through testing at shopping centres across the nation. A month later, only a handful had opened., external

Even now, the US has only tested 2.74% of its population, which puts it well behind many industrialised nations. And even the current, higher rate of test is not near the mark of 900,000 a day that a Harvard University estimate indicates is necessary to reliably identify potential virus hotspots across the country before they become major outbreaks.

Inefficiency in economic aid

Since the coronavirus outbreak hit America, the US Congress has appropriated more than $3tn to address the crisis. A large portion of that spending has been to soften the pandemic's blow to the economy, in the form of lost jobs and productivity from nationwide lockdowns and closures.

These measures include hundreds of billions of dollars in low-interest loans to businesses that can be forgiven if they don't lay off workers, direct cash payment to Americans and additional support for the unemployed.

It turns out that authorising the expenditures - done by large majorities in Congress - was the easy part. Getting the cash to the right places, on the other hand, has proven more difficult.

'We used to donate to this food bank, now we rely on it'

The rollout of the small-business programme was riddled with delays and confusion from both the private banks authorised to make the loans and applicant businesses. There also were questions about why massive corporations, restaurant chains, wealthy universities and politically-connected businesses received funds - that is, before the money ran out and had to be replenished by another congressional appropriation.

"A big problem with the relief response in the US is that it relies on many private sector intermediaries to deliver support to individuals, including in particular large corporations including large public corporations with access to financial markets," says Anat Admati, an economics professor at Stanford University Graduate School of Business.

"Meanwhile, the small business loans programs have created distortions in terms of who gets access to loans and under what terms, with insufficient accountability."

The loan programme has operated smoothly compared to the state-run unemployment system, on the other hand. Some states have fallen behind in providing what should be weekly payouts to laid-off workers. In Florida, the online registration system became so overwhelmed, the state began only accepting paper forms - and the line of applicants in some places stretched for blocks.

The president's advisors reportedly want him to concentrate on the economy now, and less on public health issues

Francis Creighton, president of the Consumer Data Industry Association, cautions that given the massive amounts of money being spent to prop up the US economy, some difficulties were to be expected.

"The point is to get the money out the door," he says. "I think that everything they've done has been really, really good. The underlying question is if anything is going to be enough given the unbelievable situation we find ourselves in."

Democrats and Republicans in Congress have talked about a third round of economic stimulus, although both sides remain far apart on where to go from here.

The coronavirus crisis has dragged on for months now, but the government responses - both good and bad - have a long way to go.

- Published24 April 2020

- Published3 April 2020

- Published25 April 2020

- Published24 April 2020

- Published1 April 2020