Coronavirus: Two Americas in the nation's capital

- Published

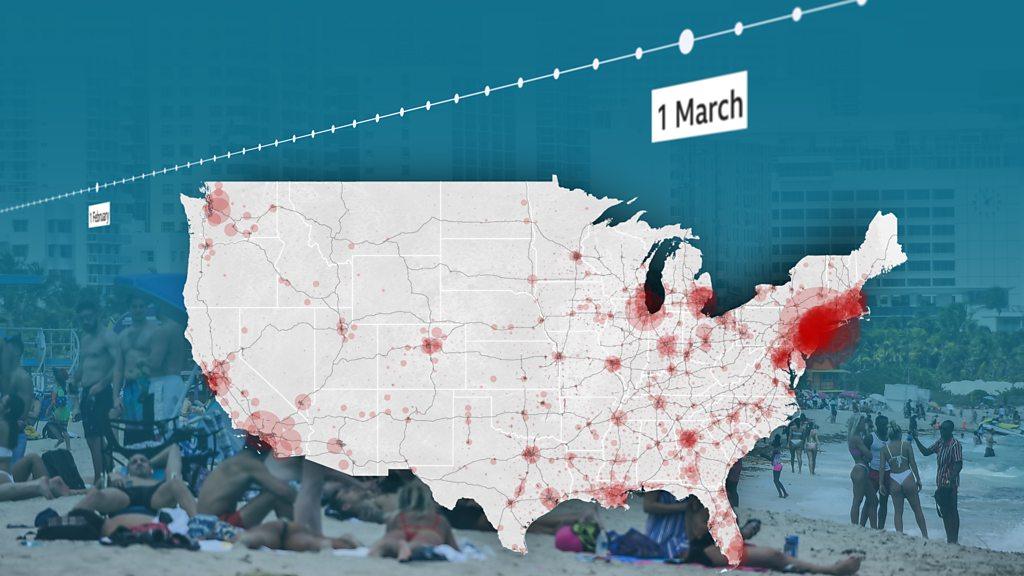

Amid political pressure to reopen America from the White House, the nation's capital city itself still isn't ready to do so - and Washington DC offers a diverse snapshot of how Americans are responding to the crisis.

It's a gloriously sunny afternoon, and a rare opportunity to enjoy a live performance from a world-class musician.

Residents of Washington's Capitol Hill district are still under orders to shelter at home. But they're taking a break from the pandemic, sitting on front steps and in socially distanced lawn chairs, listening to a neighbour in search of an audience after he had to cancel a tour.

Just down the road at the Capitol building itself, lawmakers are gradually returning to work, to deal with matters less lyrical.

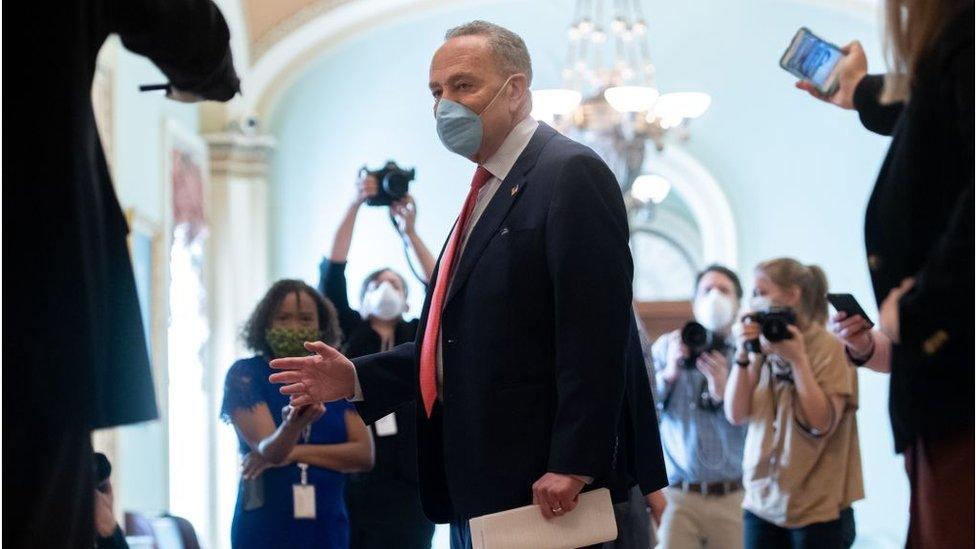

"There can be no doubt that this will be one of the strangest sessions of the United States Senate in modern history," said Minority Leader Chuck Schumer when it opened at the beginning of the month.

Members wearing masks sit in chambers that feel more empty than occupied.

Senators, like Democratic leader Chuck Schumer, wore masks in the chamber

But while political pressure to open up the country is mounting in the capital, the city itself isn't ready yet for business.

You just need to drive 10 minutes to see it's still on emergency footing. In DC's majority-black neighbourhoods like Anacostia, the virus has laid bare longstanding social and racial divides.

I caught up with local councillor Trayon White, who's campaigning for re-election in Ward Eight, Washington's poorest.

He's hard to miss - wearing a florescent yellow track suit and surrounded by a team of young men in blue and white camouflage outfits with matching blue surgical gloves. They're distributing bags with bleach and toilet paper while the councillor hands out masks with his name on them and takes selfies with constituents.

But behind the smiles for the camera is a disturbing reality.

The pandemic is killing black people at an alarming rate, including Mr White's own grandmother. Eighty percent of the city's Covid-19 deaths are African Americans, even though they're less than half its population.

"We have some of the highest health disparities per capita in the country in this community," he says.

"From high blood pressure to diabetes, to asthma, you name it we have it. So we're fighting two monsters at the same time. You are talking about the people that are already at the bottom and have been pushed down even further."

The city has increased testing in predominantly black and Latino neighbourhoods and recruited former First Lady Michelle Obama to record calls to spread the word.

And just this week the mayor, Muriel Bowser, opened a 437-bed field hospital in the convention centre. It's empty, but she called it an insurance policy. She said the number of confirmed cases was less than initially predicted, but still climbing.

Her cautious approach to reopening, however, means she could be headed for a collision with the capitol region's largest employer, the federal government. Especially as its most famous resident, President Donald Trump, is pushing to get the nation back to work.

"I hope that the President is right…that we will recover," Ms Bowser said recently. "All of us want to get open, we just want to do it in a safe way. The last thing we want is to be back here in the fall, having lost all of the gains of social distancing."

Mr Trump is eager to return to normal, but just around the corner from the White House is the new normal: a venerable Washington institution is serving its own servers, handing out meals to its laid-off employees.

The Ebbitt Grill is the oldest operating restaurant in DC, a favourite watering hole for politicians, now running a bare bones takeaway business. It can't go on like that for long but it's wary about reopening.

David Moran, one of the Grill's senior directors, says areas of the country that "unfortunately" reopen quicker than recommended by guidelines set by the Centers for Disease Control could provide a "roadmap of what works and what doesn't work".

"Just because the politicians or the government tell you that you can open doesn't mean you have to open that day," he says. "I think we're going to do what's right by our guests, right by our employees, and right by our integrity."

Back on the streets of the Capitol Hill neighbourhood, musician Frederick Yonnet is still captivating the curbside crowd. He's a harmonica player who's performed with the likes of Prince, Stevie Wonder and Ed Sheeran. Now his stadium is his house, and his audience is his neighbours.

"Thanks to this we are meeting more neighbours than I've ever met since I moved here," he says. "We've discovered that some guy over here is an astronaut, another one works for a news network. Music is a universal language and it needs to be spoken, especially in difficult times like this."

It's a brief moment of harmony on the Hill, as this tug of war between the need to reopen and the desire to stay safe, plays out beyond them.

- Published11 May 2020

- Published7 May 2020

- Published12 May 2020