Coronavirus: How bad is the crisis in US care homes?

- Published

Families have been unable to visit loved ones inside

Elder care homes across the US have been hard-hit by the virus - though the true extent of the severity remains unclear, months in. One thing is certain, however - Covid-19 has yet again highlighted long-standing flaws in America's health system.

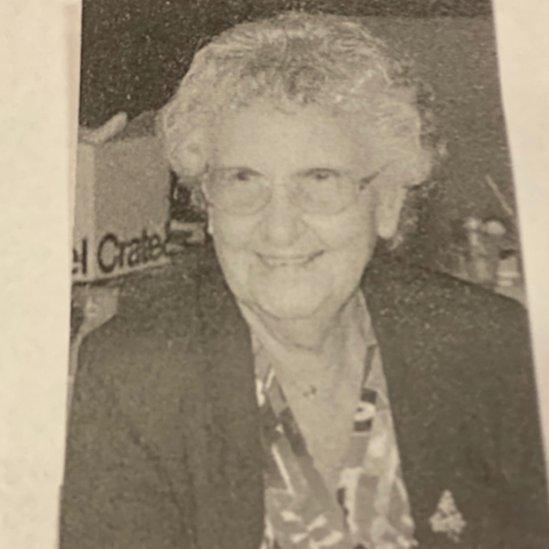

When Michael Colwell received the call that his mother-in-law Helen Osucha had passed away at her nursing home in Geneva, Illinois, he says they told his family the 97-year-old died peacefully in her sleep.

A day later, the funeral home that had received Helen's body told them she had Covid-19.

As they grieved, holding Helen's funeral with family calling in on computer screens, the question remained. Why weren't they told?

"It just didn't feel that this is the way the world should work."

Mr Colwell says the home informed them that there were "a case or two" of Covid-19, but they had no idea of the full extent.

"They telephoned us on the day of her death, late in the evening on the 26 of April and said she had passed away peacefully in her sleep. The fact that that's how she went gave my wife some comfort. But then to learn the next day that she died of Covid-19 - it was a very big shock."

Helen was a part of the Greatest Generation, Mr Colwell begins when asked to describe his mother-in-law. She lost a brother in World War Two. Her husband was a B-17 navigator, and they married when the war ended.

For years, she worked at a longstanding Chicago restaurant - the Como Inn - as a bookkeeper and waitress, making many friends among the close-knit Polish community. She often held family gatherings and was an active member of her church - a "kind-hearted, generous woman".

"Maybe we could've said a prayer or done something," Mr Colwell says. "Initially when they restricted visits from family because of the pandemic, we were told that if the [resident] was in fact dying, they would have hospice come in and we would be allowed to go in and see her.

"And of course, that never happened because we didn't know."

Mr Colwell's lawsuit against Bria is one of six now levied against the facility over its coronavirus response.

Bria has placed the blame on a lack of testing, calling the virus a "silent enemy impossible to detect and difficult to defeat", and says they followed public health guidelines as the situation evolved.

A spokeswoman for the home told the BBC: "We mourn the loss of our patients, for many of whom we cared for many years, and we share the anguish of their loved ones."

What does the data show?

So far, facilities across the US have reported over 126,400 confirmed Covid-19 cases leading to the death of 35,517 residents and hundreds of staff to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Bria of Geneva has reported 16 Covid-19 deaths to CMS.

Johns Hopkins University puts the US death toll at over 133,000 as of 10 July - which means that by current federal figures, care homes account for a quarter of all US coronavirus deaths.

But other counts, drawing from state data, say the toll could be far higher: over 50,000, according to reports by the Wall Street Journal, external and the New York Times, external.

An analysis by the non-partisan Foundation for Research on Equal Opportunity found 45% of US Covid-19 deaths came from nursing homes - a group that makes up just 0.6% of the US population.

But that still isn't the full picture.

Many submissions to CMS have not passed data quality checks; homes are also not required to provide data from before May. This means that while some states seem to have shown promising numbers so far, there are caveats.

Why is it so bad?

University of California, Davis, Professor Debra Bakerjian, who worked as a nurse in the industry for 25 years, notes that the situation with Covid-19 has been changing rapidly while facility struggles around testing, understaffing and equipment have remained the same.

The lack of testing early on "was bad in hospitals [and] was worse in nursing homes", she says, though it has since been improving. On top of that, guidance over how to diagnose coronavirus symptoms kept changing.

Residents in care homes are nearly impossible to isolate to begin with. Most facilities have only one or two private rooms. People share hallways, bathrooms, dining areas. A limited number of staff are responsible for multiple individuals, sometimes across buildings or homes throughout the community. Outbreaks in nursing homes in general are not uncommon.

Ambulance workers sanitise after dropping a patient off at a New york nursing home

When Covid-19 began to surge, the biggest concern for state and national officials was whether hospitals would be overwhelmed.

"But nobody was paying attention to what was happening in nursing homes, who were a much higher risk population," Prof Bakerjian says. "It was going to be an even bigger problem because they don't have the resources a hospital has - in terms of nursing resources as well as having the supply of appropriate personal protective equipment."

Over 1,800 care homes nationwide reported to CMS they would run out of N95 masks in a week. Over 500 said they will soon run out of gloves. Dozens of facilities currently have no gowns or hand sanitiser.

Homes have also had to meet changing requirements with reporting to meet local, state and now, federal standards.

A clearer federal response may have also helped avoid the contentious policy decision by some states to have nursing homes take in Covid-19 patients from hospitals.

New York's Democratic Governor Andrew Cuomo has become the face of this policy - and continued to defend it - though other states, including New Jersey, Michigan and California, enacted similar rules before reversing them.

But New York in particular has been under national scrutiny as, for months, it was the national epicentre. In its care homes, the state has seen over 10,500 confirmed cases of the virus and has lost at least 4,092 residents to Covid-19, according to CMS data, from a population of nearly 90,000. Local reports say the death toll is thousands above that figure.

In the states that also issued these orders, results were unfortunately similar. A ProPublica report, external found neighbouring New Jersey lost 12% of its home residents to the virus, compared to 1.6% in Florida, which did not enact such a policy.

Lawsuits across the country

Lawsuits against nursing homes like Bria have been filed across the country as family members grieve and reports of shocking conditions continue to emerge.

In New Jersey, the state with the highest average case count in care homes, 15 families are suing a facility that made national headlines when nearly 20 bodies were found stacked in a morgue built to handle just a few. Several families in Kentucky are suing a home for not properly educating staff about wearing protective equipment in Covid-19 patient rooms amid over a dozen deaths.

At the heart of all these cases is the simple fact that losing a loved one like this in a pandemic means families rarely have the chance to say goodbye, to grieve together, to have closure.

"No matter how long a parent lives it's always a difficult thing to lose your parents," Mr Colwell says.

What about staff?

It isn't just patients and families taking issue with how care homes have handled the pandemic. There are reports of staff being told to work despite having Covid-19 symptoms, not having access to testing, not receiving proper training regarding Covid-19 or the need for personal protective equipment.

"One thing Covid has shown us is that we are failing as a society here in the US to take care of the people who took care of us when we were kids," says Christopher Laxton, executive director of the Society for Post-Acute and Long-Term Care Medicine.

"We need to completely re-engineer and rethink how we do elder care in this country."

Residents at a California nursing home were evacuated after a number of residents tested positive for Covid-19

Part of that involves recognising the struggles of staff, who Mr Laxton calls "the heroes of this pandemic".

"They don't get any glory, usually they get a lot of blame [but] they're doing what they can under unbelievable circumstances."

Bria's spokeswoman also cautioned that lawsuits send a "dangerous message" to staff, and spark fears that paralyse and distract medical providers.

When it comes to situations like Bria's, Mr Laxton notes that it can be difficult for the coronavirus to stand out in a population that is already sick.

"If for example, a staff member notices Mrs Jones is experiencing shortness of breath, that may well be because she has congestive heart failure," he says, and that's what they'll try to manage first, especially without access to testing.

He notes there have been many success stories too - such as facilities where staff moved into the homes in order to curb the spread of the virus, despite a lack of adequate protective equipment for themselves.

So what happens next?

Democrats in the House of Representatives on 16 June sent letters to five for-profit nursing home companies dealing with coronavirus outbreaks, asking for documents related to these outbreaks, including data on testing, staffing levels, and legal violations, as well as information on how federal funding has been used.

A group of House Republicans on the same virus subcommittee have requested information from five Democratic state governors - Tom Wolf of Pennsylvania, New Jersey's Phil Murphy, Michigan's Gretchen Whitmer, California's Gavin Newsom and Mr Cuomo - over their policies to have homes take in Covid-19 patients.

Amid these inquiries, Covid cases have been rising across much of the US. Problems with testing and equipment are occurring at healthcare facilities nationwide.

"We haven't seen the extent of the problem," cautions Prof Bakerjian. "Our numbers are still going the wrong direction, though I think there's a much more concerted effort now to try to make sure that nursing homes at least have the resources that they need."

From education to understaffing to facility regulations, the industry has long been under-resourced and faces complicated systemic issues. While some - like the Colwells - hope lawsuits will result in real changes, others, like Mr Laxton, worry that after the pandemic, nursing homes will be forgotten once more.

"It's an issue of value, of what we as a society think is important," Prof Bakerjian adds.

"We wouldn't stand for this if it was in our acute care hospitals where we were taking care of our children and our younger, working people."

- Published6 April 2020

- Published8 July 2020

- Published5 July 2022

- Published15 May 2020