Coronavirus: Things US has got wrong - and right

- Published

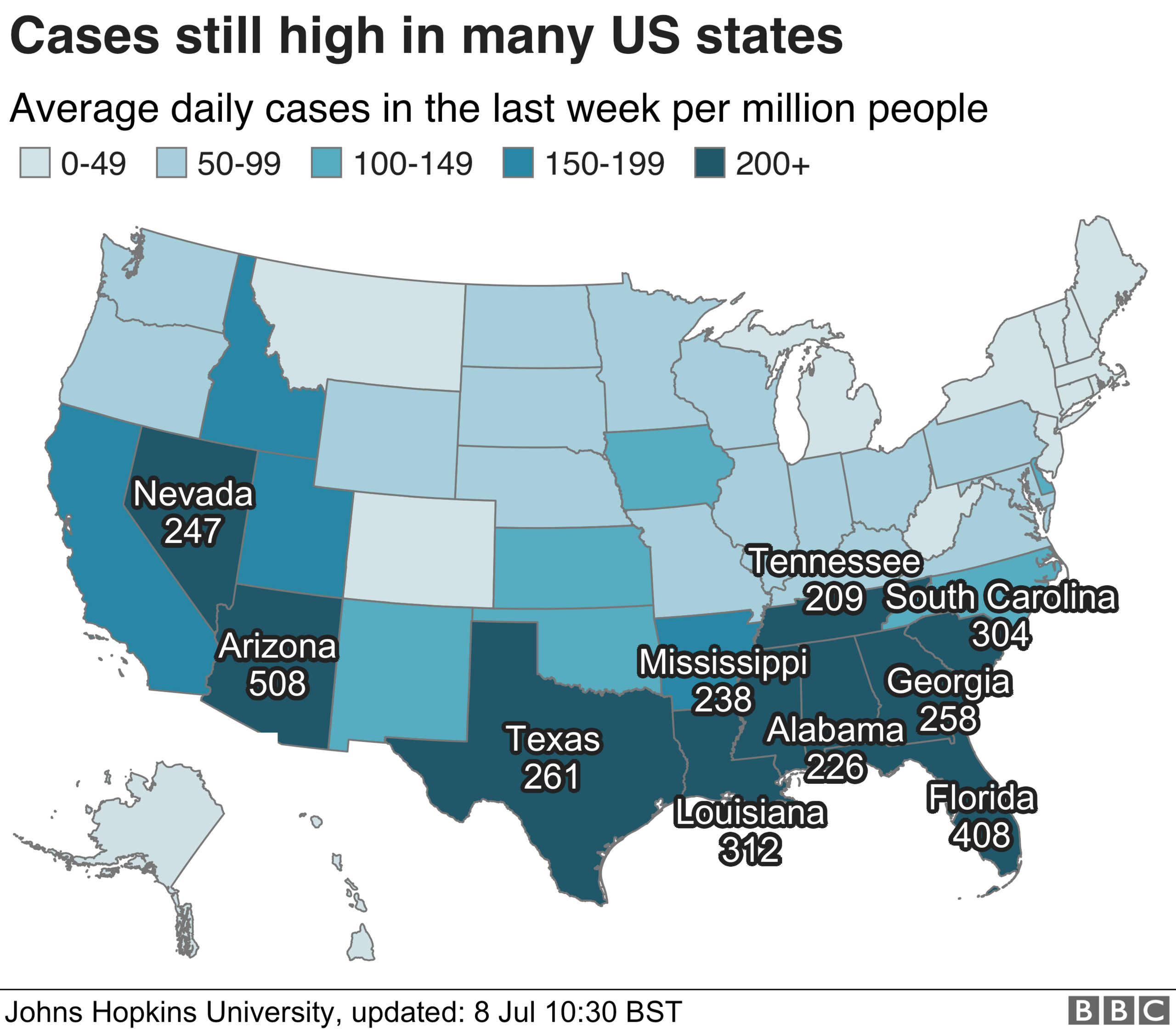

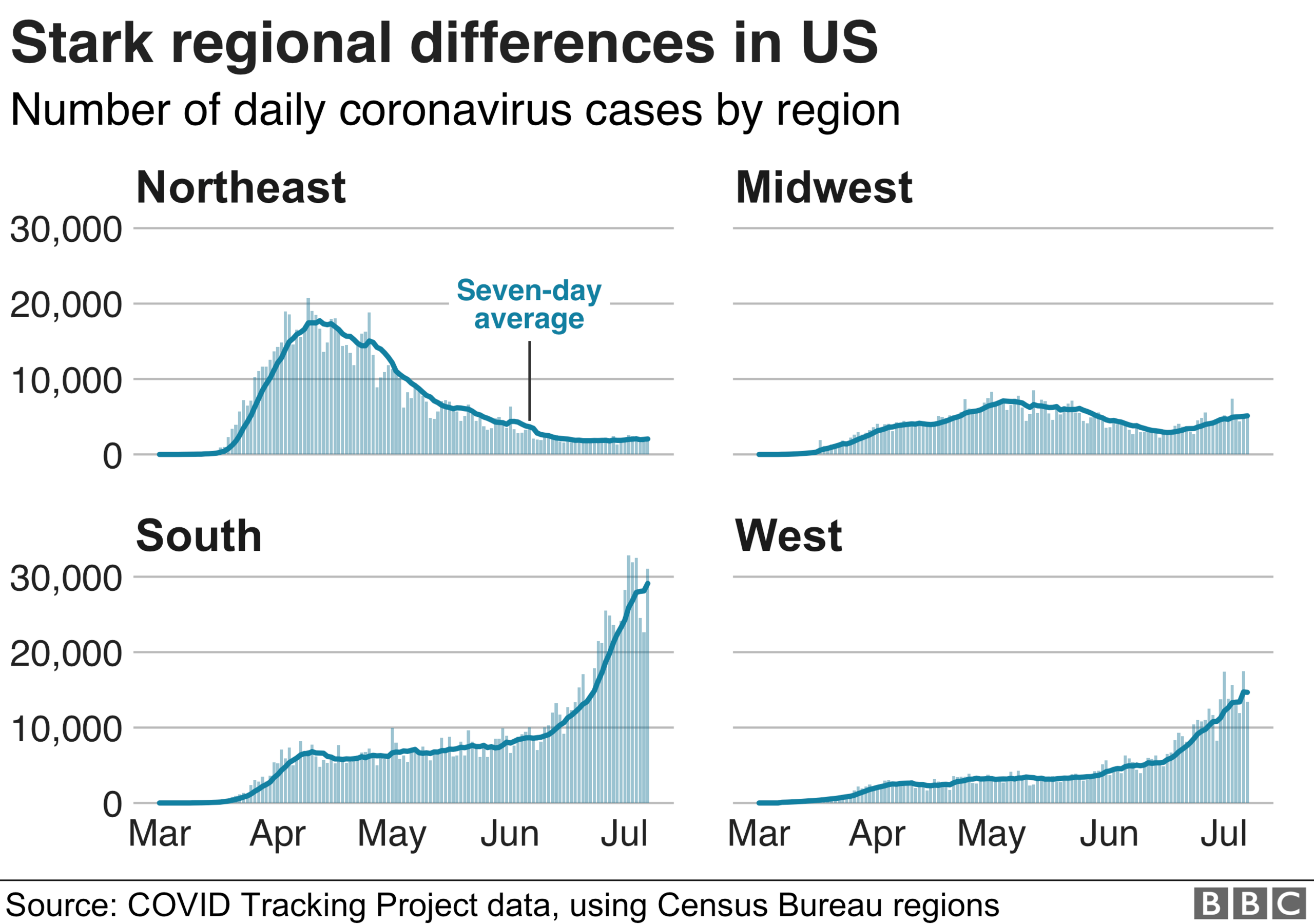

So much for a summer lull in the coronavirus pandemic. Instead, the US has seen a resurgence of the disease in numerous states, particularly across the south and west.

The US nation as a whole has topped 60,000 recorded daily new cases this week.

Did it have to be this way, though?

Other industrialised nations, in Europe and Asia, pursued more rigorous mitigation plans, ramped up testing and contact tracing earlier, and eased restrictions in a slower and more co-ordinated fashion.

They have not, at least so far, seen a resurgence of the virus similar to the one the US is currently experiencing.

The US state of Arizona, for instance, is currently registering as many new cases of coronavirus as the entire European Union, which has a population 60 times greater.

It makes for a gloomy review of what's gone right and (mostly) wrong, as the US enters its fifth full month of a pandemic that has no end in sight.

WHAT'S GONE WRONG

States opened too quickly

A month ago, the coronavirus numbers in the US appeared, at the very least, stable. The spread of the disease had been slowed, as the daily tally of new cases plateaued.

That prompted a number of states - including Texas, California, Florida and Arizona - to move forward with plans to ease off public shelter-in-place and business closure orders.

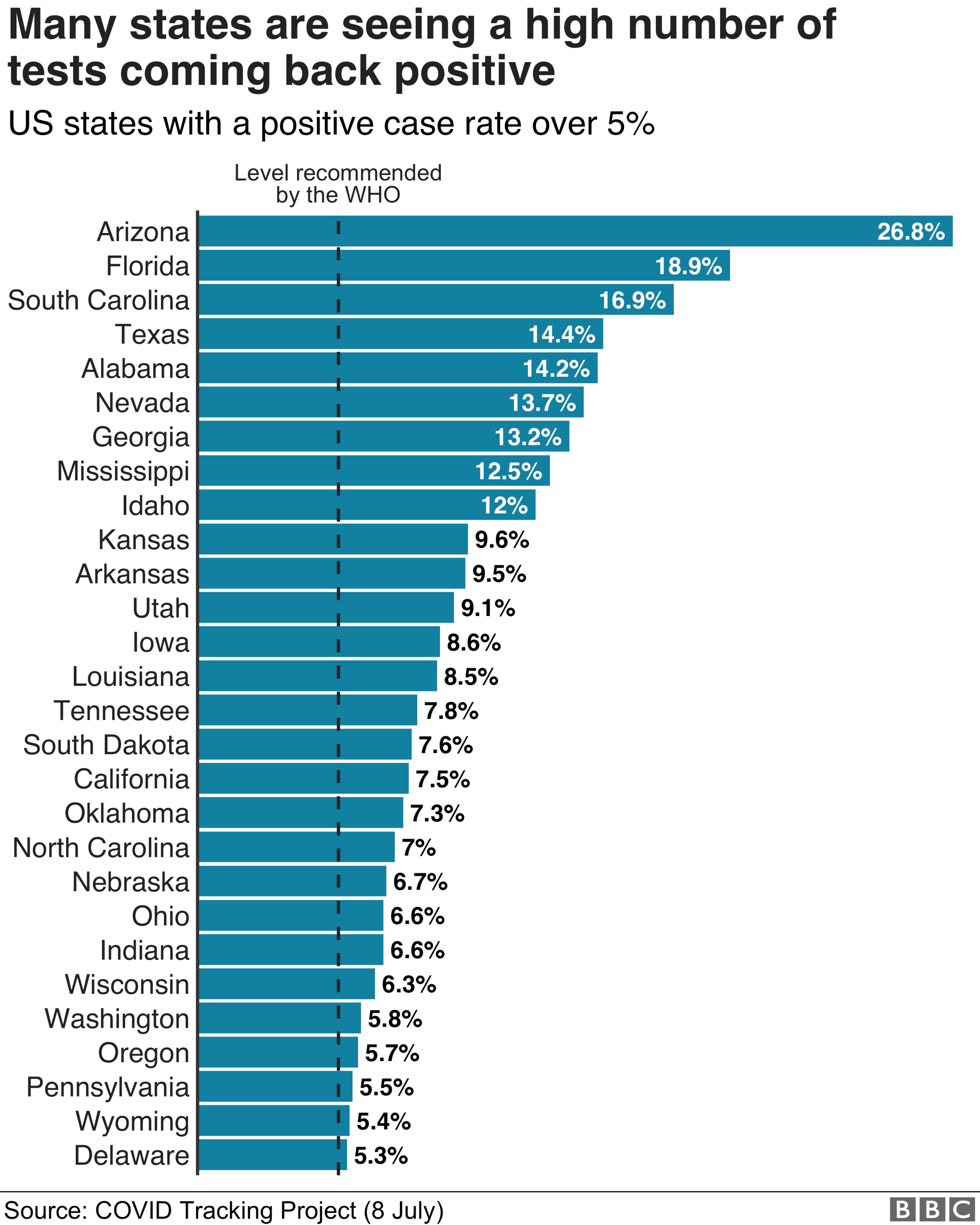

Many of these states moved ahead despite not hitting the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended benchmarks for doing so, such as a 14-day drop in cases and less than 5% of tests coming back positive for the virus.

It turns out, the overall national numbers were misleading, as states that were hit hard early, such as New York and New Jersey, were experiencing declines, while numbers in other states were beginning to inch up.

They're not inching up anymore, they're surging - and the worst, as far as hospitalisations and fatalities, could be yet to come.

Now Texas, California and Arizona, among others, have re-imposed business closure orders and mandated mask-wearing, which has been determined to reduce the spread of the virus. It may be too little to avoid another public-health crisis, however.

"We opened way too early in Arizona," Phoenix Mayor Kate Gallego, a Democrat, said in recent television interview. "We were one of the last states to go to stay-at-home and one of the first to re-emerge."

The 8,181 Covid-19 hospitalisations in Texas on Sunday were yet another record high. In Arizona, 14% of coronavirus tests are positive for the virus.

California, an early success story in limiting the spread of the virus, has seen a 90% increase in cases over the past two weeks, after the state in May allowed local authorities more discretion in businesses re-openings.

Why coronavirus cases are surging in Texas

The surge in cases is also again leading to delays and shortages in testing - an area that had appeared to be a strength for the US after a halting start.

Without adequate testing, it will be significantly more difficult to identify and isolate new cases and locations where the virus is spreading unchecked.

"We're right back where we were at the peak of the epidemic during the New York outbreak," former Food and Drug Administration commissioner Scott Gottlieb said during a television interview on Sunday.

At least for the moment, the rate of daily deaths has not reached New York levels - but that may only be a matter of time, as the current cases progress.

"It is already too late," says Luiza Petre, a New York City physician and professor of cardiology at the Mt Sinai School of Medicine. "We're at a point of no return where it will be very, very difficult to restrain this pandemic."

Mask-wearing became partisan

Compounding the decision by some states to prioritise reopening in spite of warnings from public-health officials, one of the best methods of limiting the spread of the virus - wearing a face covering - has become mired in partisan acrimony.

A June survey by Pew Research Center, external found that only 49% of conservative Republicans said they wore a mask most of the time in the past month, while that number is 83% among liberal Democrats.

Conservative opposition becomes even more entrenched at the prospect of government-enforced mask mandates.

"Kansans don't need Laura Kelly and the nanny state making decisions best left to individuals," Bill Clifford, a Republican congressional candidate in Kansas, said in response to a mask order from his state's Democratic governor. "State mask mandates violate the principles of individual liberty and local control upon which America was founded."

Donald Trump himself has contributed to the division, mocking a reporter who refused to remove his mask during a press conference as being "politically correct" and retweeting a Fox News journalist who suggested a photo of Joe Biden in a mask was damaging to the Democrat's image.

Few Trump supporters wore masks at his Tulsa rally

The president has steadfastly refused to wear a mask in public events - a position that has clearly registered with his supporters. At the president's campaign rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, in June, few in the crowd chose to use face-coverings, and most disregarded social-distancing suggestions.

Public-health officials aren't free from blame, either. Early on, they declared that face-coverings were only helpful for front-line medical personnel.

While the real motivation for such statements may have been to reserve limited supplies to those most in need, the end result was a message that was muddled and shifted as the pandemic progressed.

Public complacency

While some state governments have eased restrictions on public gatherings and allowed businesses to re-open, they have frequently accompanied such moves with recommendations that individuals make decisions based on medical advice and common sense.

Those recommendations have been, to put it mildly, not always heeded.

Summer holidays led to mask-less crowds in reopened bars and restaurants, public parks and beaches. And while masks were a fairly common sight during the mass anti-discrimination protests that swept the nation in the past month, social-distancing practices were essentially non-existent.

Can you become immune to coronavirus?

The numbers behind this new coronavirus surge indicates that many of the newly infected are younger Americans, who have been among the quickest to return to in-personal socialising. Some political leaders, including the president, have essentially encouraged this, asserting that the young and healthy have little to fear from the virus.

"Now we have tested over 40 million people," Trump tweeted on Saturday. "But by so doing, we show cases, 99% of which are totally harmless."

That flies in the face of public-health studies that have shown that a fifth of Covid-19 cases result in severe respiratory distress.

"We have data in the White House task force," US Food and Drug Administration Commissioner Stephen Hahn on Sunday, refusing to reject Trump's 99% figure as false. "Those data show us that this is a serious problem. People need to take it seriously."

But a president downplaying the severity of the disease can go a long way toward undermining words of warning from his subordinates.

Education approaching crisis

The coronavirus resurgence has also lit the fuse on a bomb that is set to explode in just a few months. September is when American children traditionally head back to classrooms across the nation, and it's becoming clear that nothing close to a normal educational experience is waiting for them.

School administrators are starting to unveil their plans for the coming academic year, and in many cases it's a blend of in-person and distance learning with the hope that it's enough to keep their institutions from becoming staging grounds for spreading the pandemic.

Already some teachers' unions are rebelling at the suggestion that educators - including elderly or those at greater health risk - return to classrooms with what they view as insufficient protection or preparation.

"Our educators are overwhelmingly not comfortable returning to schools," wrote the head of a Washington DC area teachers' union. "They fear for their lives, the lives of students and the lives of their families."

A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?

CONTACT TRACING: 'He asked me: Am I going to die?’

MEETING FRIENDS: How can I do that safely?

GLOBAL TAKE: Which country has the most generous bailout?

THE LOST SIX WEEKS: Missed chances for US to contain outbreak

Meanwhile, parents facing the prospect of having to manage more de-facto home-schooling and figuring out how to care for and supervise their children while they, themselves, are being asked to return to their workplaces.

Trump, despite campaigning in 2016 against federal involvement in local education systems, is already pressuring schools to open back up on time. He's called for the CDC to revise its guidance to make it easier to reopen school buildings and threatened to cut off federal funds for those that don't comply.

Florida, a Republican-controlled state currently in the midst of a widespread coronavirus outbreak, already has ordered its schools to open for classes at the end of August.

The president's rhetoric, delivered via Twitter, seems destined to politicise yet another aspect of the coronavirus response, again putting local officials in the unenvious position of balancing community health concerns with demands to return to normal times that seem increasingly out of reach.

WHAT'S GONE RIGHT

New York recovery

Although the coronavirus situation in many US states in the south and west has become increasingly dire, what was once the epicentre of the outbreak - New York - has made remarkable improvements.

Daily deaths, which peaked on 8 April at 799, have dropped to single digits. Only 1.38% of the state's coronavirus testing last Friday returned positive results.

As other areas have re-imposed lockdown restrictions, New York has begun reopening many public facilities and private business such as salons, tattoo shops and youth sport leagues. Indoor restaurants, however, remain closed.

"What happened in New York should have been a cautionary tale for the other states to pay attention and learn to create a more centralised strategy," says Ms Petre, the New York City cardiologist. "New York is a success story."

As the state continues to ease its mitigation restrictions, there is the risk that the virus will return resurgent.

"We've been through hell and back, but this is not over," said New York Governor Andrew Cuomo. "This can still rear its ugly head anywhere in this nation and in this state."

Economy stabilised - for now

A funny thing happened on the way to the next Great Depression. The US economy, expected by many forecasters to be in a devastating tailspin, stabilised and began to improve.

May unemployment figures, predicted to top 20%, registered at 13.3% instead. Then, in June, they ticked down to 11.4% - an indication that the workplace haemorrhaging had been stopped much earlier than expected.

Meanwhile, key stock indices have bounced back from their late winter beating. By 2 July, the Dow Jones Industrial Index had recovered 66% of its losses from its February record high. The Standards & Poor's 500 Index, a broader measure of stocks, has made up 77% of its losses this year.

What Anthony wrote in April and May

Other economic indicators offer similar signs of an economic resurgence.

The strength of the recovery has largely been attributed to the push by states to quickly lift virus mitigation orders and federal action to provide economic support for businesses and individuals hit hardest by the virus.

The return of business closures in several states could mean the economic good news will be short-lived.

Meanwhile, most of the stimulus measures passed by Congress have either run their course or are set to expire soon, while there appears little prospect of further action.

Living through the threat of eviction in the pandemic

"Since it is now clear that the effects of this crisis will be felt at least until the end of 2020, that relief package will not be enough," says Jill Gonzales, an analyst with the personal finance website Wallethub.

Science advancing

While the coronavirus afflicts a growing number of US states, the American medical community continues to grind away at treatments and, ultimately, a vaccine.

Remdesivir, an antiviral drug, has shown promise in limiting the severity of the disease in hospitalised patients (prompting the US government to strike a deal with the drug's manufacturer to prioritise American patients).

A new study indicates that the commonly available steroid dexamethasone cut the risk of death for coronavirus patients on ventilators by a third.

There are also "encouraging signs" from experts that the use of blood plasma from recovered Covid-19 patients could help those currently suffering from the disease, although clinical research is ongoing.

"Medicine has evolved at lightning speed," says Ms Petre. "The government has teamed up with pharmaceutical companies and a lot has been done, which is good"

On the vaccine front, there are now several pharmaceutical companies reporting positive results from early tests on drugs to boost immunity to the coronavirus.

The president is promising a vaccine by the end of the year, if not earlier, although medical professionals caution that such a timeline is far from certain.

Anthony Fauci, the chief US immunologist, would only say scientists are "aspirationally hopeful" that a vaccine would be ready by 2021.

Given that a return to normal life in the US appears increasingly contingent on a safe and reliable vaccine, a lot is riding on these hopes.

- Published6 July 2020

- Published20 June 2020

- Published8 July 2020