Trump's shortcomings make weak opponent Biden look strong

- Published

My early take on Joe Biden was that the weaknesses that made it harder for him to secure the Democratic presidential nomination would ultimately make it easier for him to win the presidency.

At a time when the Democratic Party was lurching leftwards, his pragmatic centrism would be advantageous because hard-hat voters in the Rust Belt and Starbucks moms in the swing state suburbs would find it unthreatening. Nor was his inability to rouse a crowd necessarily a drawback.

Many Americans, after all, were yearning for a presidency they could have on in the background: soothing soft jazz after the round-the-clock heavy metal of the Trump years.

Biden's geniality was the key, his smile almost his philosophy. In a politics often driven by negative partisanship - odium for your opponent more so than fervour for your own party's nominee - Biden would be hard to turn into a hate figure. Certainly, he was nowhere near as polarising as Hillary Clinton, whose negatives helped Trump pull off his unexpected victory in 2016.

Then I went to Iowa and New Hampshire and was shocked to see how the 77-year-old could barely hold a tune. Speeches became rambling soliloquies, a reminiscence from his Senate career here, a name drop from his vice-presidential tenure there. Looping and meandering, his train of thought regularly careered off the rails.

Anecdotes did not seem to make any political point; and while he spoke in vague generalities about redeeming the soul of America, he never thrashed out what precisely that meant. Still he could flash his mega-wattage grin, but he appeared before us as an ambient presence who struggled to light up a room.

The early primaries did not go well

In 30 years of covering US politics, he was the most lacklustre front-runner I had seen, worse even than Jeb Bush in 2016. The former Florida governor could at least complete a cogent sentence, even if nobody applauded when it came to an end. After Biden's fourth place finish in the Iowa caucus and his fifth place showing in New Hampshire, many of us thought the time had come for him to don his trademark Aviator shades and ride off westward into the sunset.

Instead, of course, he headed to South Carolina, where the endorsement of the influential black Democratic congressman Jim Clyburn and the support of African Americans produced a Lazarus-like return from the dead. Moderate rivals, such as Pete Buttigieg and Amy Klobuchar, left the race, coalescing around the establishment candidate deemed to stand the best chance of fending off the insurgent challenge from Bernie Sanders. Faced with the alarming prospect of a one-time socialist emerging as the party's nominee, they smashed the emergency glass in the hope that amiable Joe could put out the firebrand.

Days later, following his cascade of victories on Super Tuesday, some pundits marvelled at how Biden had triumphed in states where he had not even campaigned. But the opposite may well have been true. Biden might have performed well in places precisely because of his absence. The lesson from Iowa and New Hampshire, after all, was that the more voters saw of him, the less they were likely to vote for him. His stealth candidacy ahead of Super Tuesday helped him wrap up the nomination.

The Covid lockdown, then, has been a boon to his candidacy. The months sequestered in the basement of his Delaware residence has provided a useful cloak of invisibility. Social distancing has even helped neutralise an issue that once imperiled his campaign: that he was inappropriately tactile with women, creepily touchy-feely.

More importantly, the pandemic has taken the heat out of the ideological battle within the Democratic Party. Biden has reached a unity accord with Bernie Sanders without granting too many concessions to the left; one which stops short of promising universal healthcare and a Green New Deal, and avoids altogether polarising issues such as abolishing ICE (the Immigration and Customs Enforcement agency), or decriminalising unauthorized border crossings. Biden will doubtless lose some progressive support, especially amongst the young, but his campaign calculates this will be offset by attracting the backing of seniors and retirees, many of them one-time Trump supporters. Not only do the elderly vote at a higher rate than any other age group, they are also the demographic most vulnerable to Covid-19.

After the troubled start to his candidacy, it is as if the coronavirus has given Biden a political version of antibodies offering protections from his own underlying conditions.

His personal narrative also finds a mournful echo in these sorrowful times. Just after winning election to the Senate in 1972, he suffered the trauma of losing his first wife, Neilia, and 13-month-old daughter, Naomi, in a car accident. Then in 2015 he watched his son, Beau, who had survived that car accident, die from a rare form of brain cancer. Biden is naturally empathetic. It puts him on the same emotional plain as many of the 140,000 families who have recently suffered bereavement as a result of Coronavirus.

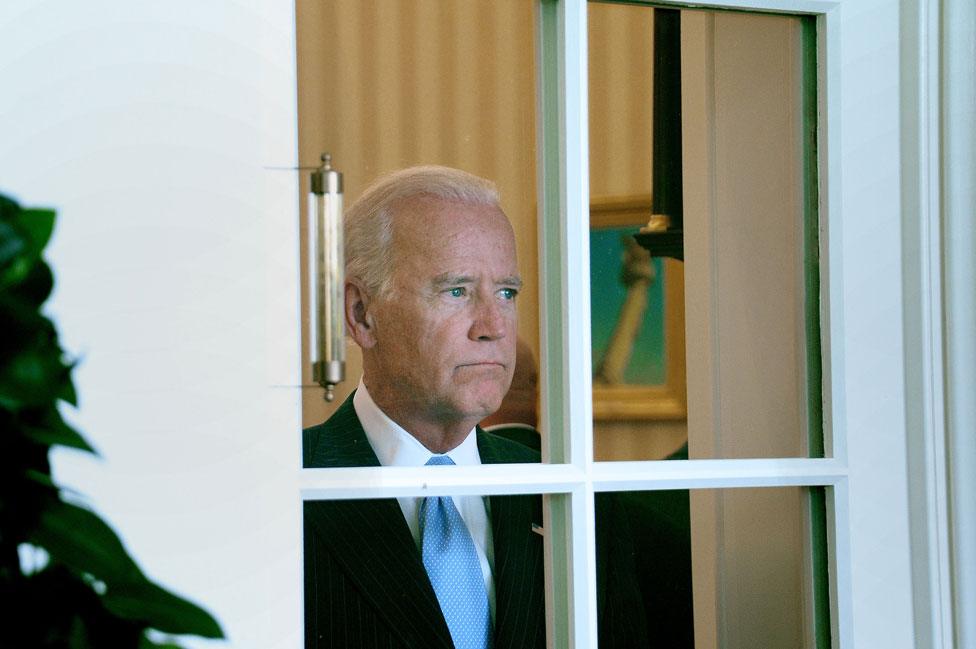

Biden with first wife Neilia and son Hunter in 1972

So far, Biden's bunker strategy has proved resistant to the Trump campaign's bunker-busting bombs - the claims of senility, the charge he has become a cipher for the radical left, the false claim that defunding the police formed part of rapprochement with Bernie Sanders. Instead, the focus has been on Donald Trump's imploding presidency.

Incumbency ordinarily bestows advantages. Since 1980, only one sitting president, George Herbert Walker Bush, has failed to win re-election. Even during the post-war period from 1945 to 1980, when only one President, Dwight D. Eisenhower, successfully completed two full terms, voters ousted just two incumbents - Gerald Ford and Jimmy Carter. Donald Trump, however, has annulled the benefits of occupancy through his mishandling of the pandemic.

The usual rule of thumb is that incumbency combined with a strong economy almost guarantees re-election - in 1992, Bush senior was primarily a victim of a recessionary economy that failed to rebound by Election Day. But Covid-19, of course, has decimated the economy, causing the most serious economic shock since the Great Depression. Voters who pointed to their soaring 401K retirement plans to rationalise their support for a president whose behaviour they often found distasteful, are shopping around. Many, the polls suggest, have already checked out.

Even some of his supposed loyalists, the non-college-educated white voters who comprise his base, are deserting him. Earlier in the year, he enjoyed a 31-point lead among this demographic, but recently that has slipped by 10 points. Polling shows that an unexpectedly high number of white voters disapprove of the president's handling of the racial protests following the alleged murder of George Floyd. They have not responded to Trump's tough law and order stance, which borrowed from Richard Nixon's winning presidential campaign in 1968 that followed a long summer of racial turbulence. Maybe Trump has failed to appreciate a key difference between then and now. In 1968, Nixon was not the president.

Biden with son Beau who died in 2015

Elections are often framed as a choice between continuity and change. Yet a selling point for Biden is that he offers voters a version of both. To the eight in 10 Americans who polling suggests believe the country is heading in the wrong direction, he is promising a course correction. Thus, he can plausibly present himself as a candidate of change. But by pledging to serve as a conventional president, returning to the norms of behaviour that Republicans and Democratic incumbents have abided by for decades, he also represents a continuum. The repair of a chain in which Trump became the missing link.

Because of the false prophecies of 2016, pundits are understandably reluctant to make predictions, and to call time on a president with a double-digit deficit in most national polls and in some battleground state surveys, too. The caution is well-advised. As Biden ventures out more often from his basement redoubt, he will face closer scrutiny. Campaign reporters will soon tire of re-writing the same Trump-is-in-trouble narrative and could easily try to inject more drama and journalistic entertainment value into the race by seizing on even the slightest slip or stumble. Then there are the vagaries of the Electoral College, which means Donald Trump could win a second term even if he loses the popular vote, as was the case in 2016. Nor can we rule out the possibility of a disputed election being decided in the courts.

Certainly, it would be an act of folly to write off Trump, who has walked away from more car crashes than any other sitting president. But over the past four years, the scar tissue has accumulated, and the pandemic has left him with self-inflicted wounds. Besides, even some of the supporters who placed their faith in him are tiring of his tricks of escapology - the boasts, the truth-twisting and the insults. This has become a Covid election. Now it is the president's weaknesses that are making Joe Biden look so strong.

- Published5 June 2020