What is the 'sovereign citizen' movement?

- Published

A 2018 mass shooting at a Tennessee restaurant was committed by a mentally unstable believer

A growing movement of people who believe that laws do not apply to them threatens police and law enforcement around the world, experts and officials say.

So-called sovereign citizens believe they are immune from government rules and in some cases - including recently in Australia and the US - have violently confronted police.

Coronavirus mitigation measures, including mandatory social distancing and mask wearing, may also be fuelling the anti-government conspiracy and spreading its message to a global minority that view the deadly pandemic as a hoax.

Who are 'sovereign citizens'?

The FBI has described the movement, which lacks any organisational structure, as "domestic terrorism" in the US and calls followers "anti-government extremists who believe that even though they physically reside in this country, they are separate or 'sovereign' from the United States".

The ideology hatched in the 1970s and grew out of Posse Comitatus, a US anti-government group that contained many followers who were anti-Semitic and believed governments were controlled by Jews.

It rose in prominence in the 1990s alongside the militia movement, says Mark Pitcavage, a researcher at the Anti-Defamation League who has followed the movement for over 20 years.

In the late 1990s, the ideology reached Canada through anti-tax groups, before later going to Australia and then the UK and Ireland, says Mr Pitcavage.

Followers in the US have issued themselves fake car licence plates

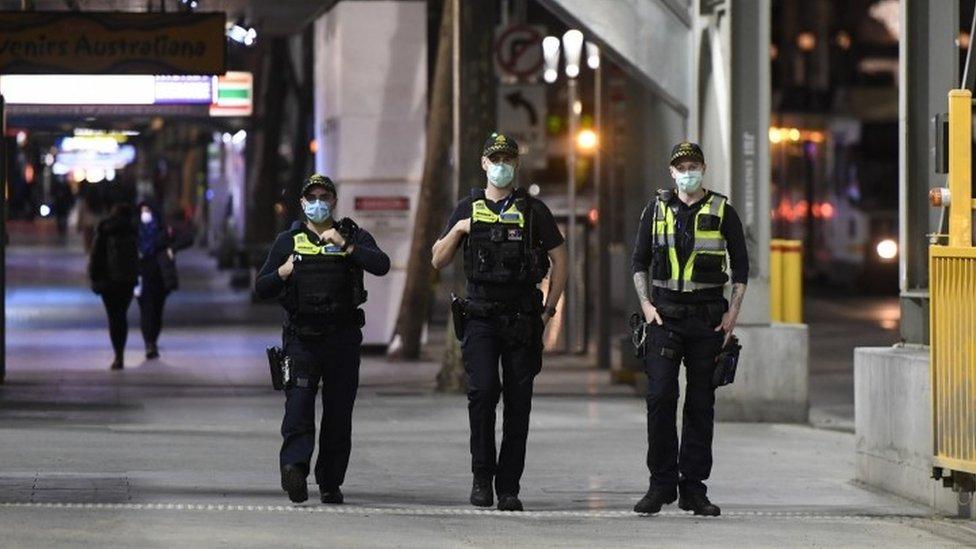

In Australia, police this week attributed a "dangerous" rise in people resisting lockdown orders - sometimes violently - to the sovereign citizen movement.

Victoria Chief Police Commissioner Shane Patton said on Tuesday that officers have been forced "to smash the windows of cars and pull people out to provide details" after they have refused to answer questions or show documents.

Analysis by Mike Wendling, Editor, BBC anti-disinformation unit

Sovereign citizens and anti-government groups became familiar to Americans in the 1990s. But any sympathy the wider public may have had towards such movements evaporated after the horrific Oklahoma City attack.

Now there are signs that their ideas are catching on again.

The political climate is to blame, including emergency coronavirus measures and anti-police sentiment after the killing of George Floyd.

Along with groups like the Boogaloo Boys, Three Percenters, and the Proud Boys, sovereign citizens are one of the fringe, and often overlapping, blocs who've popped up on social media and on the streets.

Their ideas travel.

When I covered an anti-lockdown protest in London in May, the first person I encountered was a man eager to tell me why the government had no legal power over him.

But it's the US where the greatest potential for violence lies - particularly as Americans get deeper into a pandemic and a potentially fraught election campaign.

In Singapore, a country known for adherence to rules, a viral video in May this year showed a 40-year-old woman refusing to don a face mask, telling people "I'm a sovereign… This is something people are not going to know what it is".

"It means I have nothing to do with the police, it means I have no contract with the police. They have no say over me," said the woman, who was later sent to a mental health facility.

An officer enforcing Melbourne's lockdown had her head smashed into the ground by a 'sovereign citizen'

In the US, suspects of violent crimes - including a man accused of beheading his landlord in a rent dispute last week - have claimed to be immune from prosecution as sovereign citizens.

One of the ideology's most famous adopters was Oklahoma City bombing conspirator Terry Nichols, who filed endless frivolous lawsuits against the government in the years before the 1995 attack on a federal office building which killed 168 people.

The sovereign citizen movement is different from the militia movement, which puts more emphasis on paramilitary weapons training and organisation, experts say.

Sovereign citizens - which also go by many other names including constitutionalists, common law citizens, freemen, and non-resident aliens - favour legal arguments.

QAnon is a bizarre conspiracy cult that has surged in popularity during the coronavirus pandemic.

It also differs from the QAnon conspiracy theory which believes President Donald Trump is saving the world from evil, because sovereign citizens view all government figures, including Mr Trump, as illegitimate.

What do sovereign citizens believe?

There are a multitude of theories that followers believe, experts say, cautioning that it is hard to determine the number of believers worldwide due to a lack of structure.

The general ideology is based on the belief that the original government set up by the US founders, which most adherents refer to as "common law", was slowly and secretly replaced by an illegitimate government sometime in the 1800s.

Followers around the world make similar claims about their own governments - or the British Royal Family as is the case with Australia, says Mr Pitcavage.

They believe there is a legal way to opt out of the current legal system that comes through filing documents and ending what they view as "contracts" with the government, such as driving licences and other identity documents.

Adherents are told by "redemption gurus" that they can use phrases, which they believe to have legal meaning, to "divorce themselves" from the illegitimate government, says Mr Pitcavage. They often print out and carry documents which they claim prove their status.

"And once you do that, once you have regained your sovereignty, none of the laws, rules, taxes, court orders, anything of the illegitimate de facto government have any more power or justification over you whatsoever."

Followers resist all government laws and regulations, no matter how trivial, and in the US often file lengthy legal battles against the government, which critics refer to as "paper terrorism". They sometimes film encounters with police using the phrases that they believe protect them, including "am I being detained?"

They have occasionally set up "common law courts" and issued bogus arrest warrants for US officials. Some have been arrested with fake car registration plates they have issued to themselves, or have even printed their own currency believing the dollar to be invalid. Mr Pitcavage says it's common to find European followers cite the US criminal code, which has no legal bearing there.

Some followers believe it possible to access a secret government-held fund once they become sovereign. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which oversees federal tax payments in the US, says on its website, external that the notion of "secret accounts assigned to each citizen is pure fantasy".

Some think that "by filing a series of complex, legal-sounding documents, the sovereign can tap into that secret Treasury account for his own purposes," according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks extremist groups.

Followers are often struggling financially or are people who cannot tolerate government bureaucracy, says Mr Pitcavage.

"The sovereign citizen movement, through its pseudo-legal theories and tactics, tells them who to blame - it's the illegitimate government, it's the illegitimate banking system, it's this and that. And then offers them ways out."

Related topics

- Published4 August 2020