Mayflower at 400: What we all get wrong about the Pilgrim Fathers

- Published

A Mayflower replica sailed into Plymouth in August

At a time when America is straining under the weight and contradictions of its history, along comes the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower dropping anchor off these shores. Already this year the country has been forced to confront the baleful legacy of slavery, and the systemic racism that grew from that Original Sin.

Statues memorialising heroes of the Confederacy have been toppled and removed. New landmarks have emerged, such as the words Black Lives Matter painted in fluorescent yellow letters on the doorstep of the White House.

The recent death of the African-American congressman John Lewis, a hero of the Freedom Rides and Selma, has reminded us of the climactic battles of the civil rights era in the Sixties. So at a time when we've contended with the dystopianism of the coronavirus outbreak, this unnerving new world, we've also been shoulder-deep in the events of yesteryear.

The past is always the present in the United States of America. From the modern-day Tea Party to the protesters taking aim at the Confederacy's most celebrated general Robert E Lee; from the argument over whether Washington DC's American football team should call itself the Redskins to the dispute over whether we should still honour the Founding Fathers who owned slaves, no country in the world lives and contests its history with quite such passion and ferocity. The culture wars of contemporary partisan politics, the battles that make this country seem like shared land occupied by belligerent tribes, are so often truly history wars.

Only this week Donald Trump announced the creation of the 1776 Commission to promote "patriotic education" and "the miracle of American history". Yet another cultural salvo, it was intended as a counterblast to the 1619 Project conducted by the New York Times, an online educational series named after the year that the first slaves were brought to Virginia.

So where does the landing of the Mayflower fit within the American story? What significance should we attach to the arrival of these English dissenters? How does it inform the present?

On this 400th anniversary, do the Pilgrim Fathers even merit all the fuss?

Many depictions of the first Thanksgiving meal emphasise the role of Native Americans

After all, the Mayflower didn't bring the first English settlers to these shores. Nor was the Plymouth Plantation the inaugural settlement. Jamestown in Virginia had been founded 13 years before. In the west, the Spanish had already settled Santa Fe, the capital of what's now New Mexico. And maybe it's worth stating the obvious from the outset - that the Pilgrim Fathers should not be confused with the Founding Fathers, the patriots who fought against the British in the revolutionary war, the visionaries who in 1776 launched this rambunctious experiment in democracy.

George Washington was not a passenger on board the Mayflower, a confused conflation that on occasions has been mistakenly made - although nine US presidents can trace their bloodlines to those who did make the journey, including the Bushes and FDR.

It's also a mistake to view the arrival of the Mayflower as the first interaction between white settlers and indigenous North Americans. Contact with Europeans had been going on for at least a century, partly because slave traders targeted Native Americans. When the pilgrims came ashore, a few members of the Wampanoag tribe could even speak English.

Read more from Nick

Plymouth Rock isn't Philadelphia, the cradle of the US constitution. The trans-Atlantic passage of the Mayflower is not steeped in the same national glory as the crossing of the Delaware or the storming of the Normandy beaches, despite the claims of local tourist attractions that it was the voyage that made a nation. There's no Mayflower equivalent on Broadway of Hamilton, the hip-hop homage to the father of America's financial system. If anything, the piety and theocratic tendencies of the pilgrims lend themselves more to a Book of Mormon-style parody.

Americans don't converge on Plymouth Rock with the same sense of pilgrimage as, say, Gettysburg or even Graceland. As a history student in nearby Boston in the early Nineties, I didn't even bother making the short journey myself. In the late 19th Century, there was a plan to erect a statue to commemorate the Pilgrim Fathers that would rival the Colossus of Rhodes and dwarf New York's Statue of Liberty. But this eighth wonder of the world never came to fruition, and a more diminutive memorial was built instead. As for the pavilion that encloses the lump of rock that marks the point of disembarkation, it is by American standards a modest marker - a canopy supported by 12 Ionic columns that could easily be mistaken for a municipal bandstand.

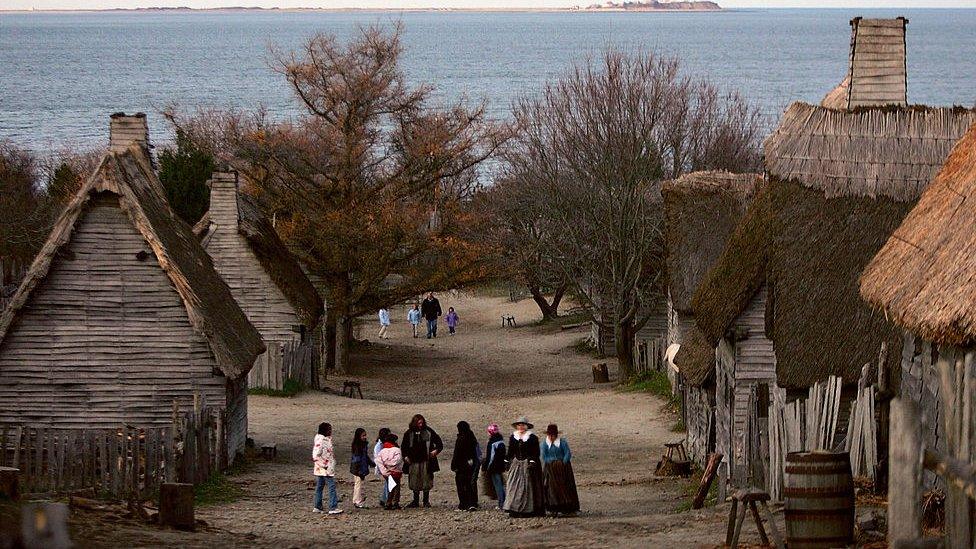

Re-enactments are held in Massachusetts nearby to Plymouth Rock

The Mayflower compact is a significant historical document, the "wave-rocked cradle of our liberties", as one historian evocatively put it. Signed by the Pilgrims and the so-called Strangers, the craftsmen, merchants and indentured servants brought with them to establish a successful colony, it agreed to pass "just and equal laws for the good of the Colony". The first experiment in New World self-government, some scholars even see it as a kind of American Magna Carta, a template for the Declaration of Independence and the US Constitution. Yet scholars at the Constitutional Center in Philadelphia suggest it had largely been forgotten by the time the Founding Fathers gathered at Independence Hall. Nor did the Pilgrims' belief in what Robert Hughes once called "the hierarchy of the virtuous" square with the more secular poetry of the Declaration of Independence that all men are created equal, and endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights. Besides, the Mayflower compact started with a declaration of loyalty to King James.

After Washington triumphed at Yorktown against the British, and this fledging nation started to assert itself in the world, the early drafters of the American story preferred to begin their histories with Christopher Columbus, even though the Italian explorer never set foot in North America. A new country that had just expelled the British did not want to be defined by its Englishness. Downplaying the Mayflower became an early act of decolonisation.

Modern-day politicians have appropriated some of the messianic language from the settler era. Ronald Reagan liked to talk of "the city on the hill", ventriloquising the language used by John Winthrop as he voyaged towards New England. But Winthrop was a Puritan rather than a Pilgrim, and set sail on board the Arbella rather than the Mayflower. It's a subtle but important difference. Unlike the Pilgrims, the Puritans, who arrived 10 years later, were not separatists. They had remained in the Church of England hoping to banish its Catholic ways from within. The Massachusetts Bay Colony that they founded to the north, the settlement that became Boston, was far more influential in the shaping of America than the Plymouth Plantation.

Taken together, though, the legacy of the pilgrims and the puritans is foundational. The work ethic. The fact Americans don't take much annual holiday. Notions of self-reliance and attitudes towards government welfare. Laws that prohibit young adults from drinking in bars until the age of 21. A certain prudishness. The religiosity. Americans continue to expect their presidents to be men of faith. In fact, no occupant of the White House has openly identified as an atheist. Also the profit motive was strong among the settlers, and with it the belief that prosperity was a divine reward for following God's path - a forerunner of the gospel of prosperity preached by modern-day television evangelists.

All these national traits have traceable roots to the Puritans. The Frenchman Alexis de Tocqueville even wrote in his seminal work, Democracy in America: "I think we can see the whole destiny of America contained in the first Puritan who landed on these shores."

The Pilgrim Fathers - or more accurately, the Pilgrim Mothers - also created a gene pool from which tens of millions of Americans continue to draw. So many US citizens claim to have ancestors who arrived on the Mayflower that you'd be forgiven for thinking this three-sailed vessel was the size of an aircraft carrier.

For all that, just about the only time the Pilgrim Fathers loom large in the national imagination is on Thanksgiving, that pre-Christmas feast of turkey and pumpkin pie when the whole of America comes to a calorific halt. This national holiday derives from the celebration marking the first harvest in 1621, when the colonists sat down with the Wampanaog Native Americans. It's been packaged up as an act of peaceful co-existence, a convivial banquet which suggests that the Pilgrim Fathers were welcomed by indigenous Americans with open arms.

Yet most of what American schoolchildren are taught about that holiday does not withstand close scrutiny. It's a mythology, not a history. There are the inconsequential inaccuracies. It's thought, for example, that venison was the main meat on offer. The modern-day menu of turkey and pumpkin pie was invented by a 19th Century magazine publisher, the Martha Stewart of her day, who had read about that first feast and lobbied Abraham Lincoln to turn Thanksgiving into a national holiday.

Protesters in June hold up a poster of George Floyd, who was killed by police in May

But it's the larger fiction that's more damaging. In a fraudulent retelling, the place of the Native Americans at that table has commonly been misappropriated and misunderstood. Thanksgiving has encouraged the idea that indigenous Americans gladly greeted white, European settlers; helped teach the new arrivals how to survive in the New World; lived together harmoniously; joined together for this slap-up celebration and then vanished from the story. It's a narrative of colonial validation; of contrived acceptance; of white comfort. It's a storyline that accepts at face value a colony seal designed by the Massachusetts Bay Colony which showed a half-naked indigenous American pleading with the English to "Come Over and Help Us." Thanksgiving has consequently become an American veil, an invisibility cloak under which the inconvenient truths of history have for centuries been concealed.

Though there was a sense of détente in those early years, largely because the Wampanoag were keen to enlist allies against a rival tribe, it quickly fell apart. Native Americans became victims of the colonists; prey to their land grabs, the exploitation of their natural resources and the fatal diseases imported from Europe from which they had no immunity. All these tensions erupted in a series of wars between the indigenous inhabitants of New England and the colonisers who robbed them of their land. This, then, is a story more of conflict than collaboration, of bloodshed, not brotherhood. Thanksgiving feasts were sometimes held to celebrate victories over the Native Americans.

As the historian David Silverman has shown in his book, This Land is Their Land, the notion that the Pilgrims were the fathers of America was seized upon by New Englanders in the late 18th Century worried that their cultural clout was not as strong as it should be as the early republic took shape. From then on, the primacy of the pilgrims, and myths of Thanksgiving, were repurposed whenever white Protestant stock felt its hegemony was threatened. This was especially true in the 19th Century, when waves of Catholic and Jewish European immigrants challenged the dominance of white Protestantism. The Pilgrim Fathers, then, were co-opted to assert the ascendancy of WASP culture - white, Anglo-Saxon and Protestant. They were used to establish a cultural hierarchy.

That dominance persists to this day. A country colonised by Anglo-Saxon Protestants continues to favour Anglo-Saxon Protestants. Not until 1960 did America elect a Catholic president, John Fitzgerald Kennedy, a politician of Irish stock. Joe Biden is seeking to become only the second.

Immigrants arriving from Europe challenged the Puritan heritage narrative

There's also a class dimension to WASP culture that means the Pilgrim Fathers are hardly regarded as populist heroes, the poster boys of the present incumbent of the White House and his Make America Great Again supporters. WASP culture has traditionally been an upper class preserve, reinforced through marriage, inheritance, patronage, and elite schools and universities.

The Pilgrim Fathers were the originators of an American class system that made Donald Trump, for all his riches, feel like an outsider. Though his mother was Scottish-born, Donald Trump is of German stock, and grew up in Queens, an unfashionable outer borough of New York. That made him "a bridge and tunnel guy" to the WASP blue bloods of Manhattan, who sneered at him as a nouveau riche property tycoon and mocked him as a vulgar presidential candidate. Those who came ashore at Plymouth Rock were the original East Coast elite, their descendants often the target of Donald Trump's anti-elitist invective.

The Pilgrim Fathers also asserted the dominance of the white race, often with murderous force. During these early years, in a cycle of reprisal killings, there were massacres on both sides. But the savagery of the white settlers was grotesque. They sought to terrorise their enemy through attacks on non-combatants, setting fire to wigwams and putting those who escaped to the sword. Then they shrouded this slaughter in the language of redemption, of how they had done the Lord's work by consigning these ungodly souls to hell.

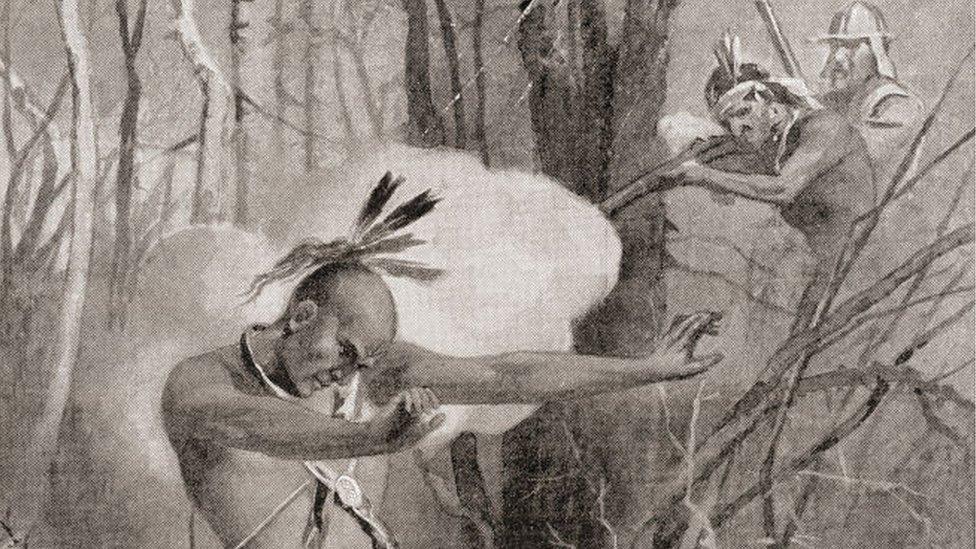

The original inhabitants of this land came to be treated like marauding invaders. When in 1675, a group of indigenous Americans banded together to fight the settlers, the dead body of their leader Metacom - whom the English nicknamed King Phillip - was treated like a trophy. He was decapitated and his head was displayed on a pike in Plymouth Plantation.

Metacom, a Native-American rebel leader, was mutilated by colonists after his death

Just as their brutality has traditionally been downplayed, the Puritans' embrace of slavery has been ignored. Not only did the colonists import African slaves, they exported Native Americans. By the 1660s, half of the ships in Boston Harbour were involved in the slave trade. At least hundreds of indigenous Americans were enslaved.

Racial division has long been the default setting of American life, and those first white settlers marked out the colour line in the blood of Native Americans. To this day, however, the Pilgrim Fathers continue to be portrayed primarily as the victims themselves of persecution, the original asylum seekers who fled the religious intolerance of their homeland.

The retelling of the Mayflower voyage as an origin story has also promoted and sustained the belief that American history starts at the moment of European settlement. This is not so much a whitewashing of the Native-American story but its complete obliteration. It's a framing of history predicated on the contemporary belief that the settlers arrived on vacant land rather than territory that had been occupied for thousands of years. This chronicle of the conquerors wilfully neglects at least 12,000 years of Native-American history, a complicated and often bloody narrative.

Racism in the US: Is there a single step that can bring equality?

When you start reconsidering the story from the perspective of the vanquished, some ground-breaking historiographical possibilities become available. In her bestselling history of the United States, These Truths, the Harvard academic Jill Lepore argues, for example, that revolution in America began not with the English settlers who eventually rebelled against the king, but rather the people over whom they ruled. In this reframing, the American patriots who took on the British are cast as the revolutionary heirs of the Native-Americans who took on the English.

At least during this year's commemorations the story of the Wampanoag people will be acknowledged. This was not true 50 years ago, during the 350th anniversary. Though a Native American leader was invited to speak at a dinner in Plymouth, Massachusetts, he was not allowed to deliver his prepared text. It had described the arrival of the Mayflower as the beginning of the end for his people, a hard truth considered too unpalatable for the city elders attending a self-congratulatory banquet.

Giving the Wampanoag more prominence in these commemorations will be regarded as a long overdue corrective, turning the celebration of a voyage into more of a quest for understanding. But make no mistake - the American history wars will continue to wage and the Pilgrim Fathers will be proxies in that battle.

- Published1 August 2020