George Floyd death: A city pledged to abolish its police. Then what?

- Published

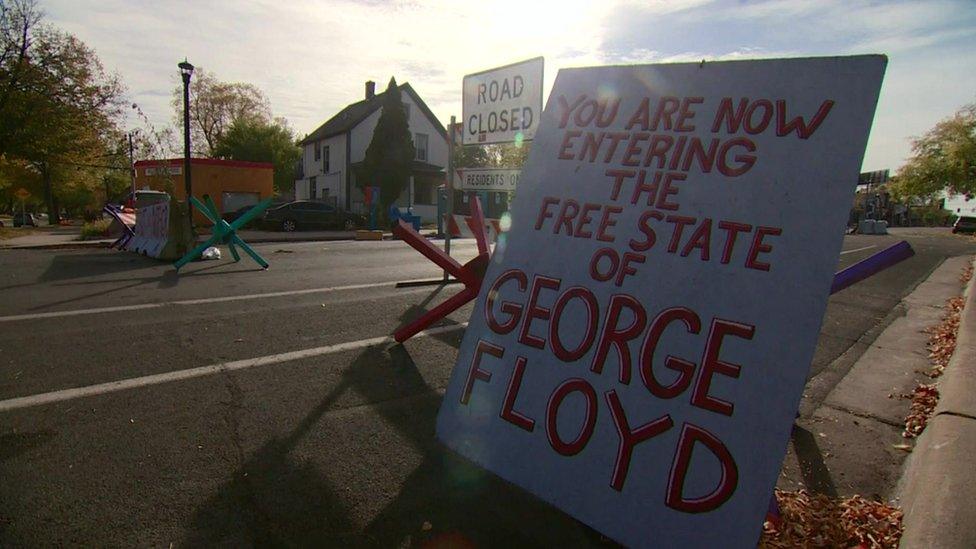

There is now a 'police free zone' at the memorial site where Floyd died

At the end of January Ade Alabi made a big investment. He bought a four-storey building with two ballrooms, three restaurants, a night club and a radio station, just down the road from Minneapolis's Third Precinct police headquarters.

By the end of May it was gone, a heap of rubble and ashes, consumed by the inferno that destroyed the police station and many of the businesses around it.

The image of the burning precinct, abandoned by police in the face of angry and violent protesters, signalled for him that something different was happening in Minneapolis.

This was the station where the four policemen charged in the killing of George Floyd worked. The explosive reaction to his slow and gruesome death, his neck pinned to the ground by an officer's knee, created momentum to change the way not only the city, but the country, is policed.

Nearly five months on, however, ambitious policy efforts to address police violence in Minneapolis have slammed into bureaucratic roadblocks and public opposition.

Cathy Spann wants the police to do more to stop surging gun violence in her area

In the charged atmosphere after the Floyd killing, city counsellor Alondra Cano says she "knew in my gut that we had to do something different… to send a message nationally that would rupture through the traditional approach", to police misconduct.

Reform hadn't worked, she said. It was time now to transform.

So in early June a majority of city council members took a step that shook Minneapolis and drew national and international attention. They pledged to dismantle a policing system long accused of racism, and build something new - "to end policing as we know it".

They then proposed an amendment to the city's charter to put on the November ballot. It called for replacing the police department with a new entity of community safety and violence prevention.

The proposal was short on detail but council members said there would be a public engagement process to fill in the blanks.

Councilwoman Cano wanted to "to end policing as we know it"

Instead, they faced public opposition, most vocally from North Minneapolis, a largely black neighbourhood, which saw a dramatic rise in gun crime and robberies after Floyd's death. Residents have become so alarmed they are suing the city.

"We have historically had victims of violence by police," said Cathy Spann, a community organiser, at a recent neighbourhood gathering. "But we are under siege right now with gunfire every single night. The council has to bring in extra force to stop this from happening!"

Crime is up in North Minneapolis since Floyd's death

The consensus at the backyard gathering was that the council's declaration had emboldened criminals and demoralised the police department. Whatever the case, dozens of officers have left the force, quitting or claiming medical leave.

"We want to reimagine community policing, desperately, to save the lives of our young black and brown men and women," said Jon Lundberg, whose house was hit by random gunfire last week.

"But what we need now is to reinstitute some systems of control. Because right now it's off the hook, it's off the chain."

Some city counsellors have begun to backtrack given the backlash. Cano is not one of them.

She says the proposal was meant to set the direction for a complex and lengthy process.

"Now is where we should be digging deeper and tackling those very important questions around why are we seeing an increase in gun violence and robberies and we shouldn't shy away from that," she says.

"That doesn't mean what we did on 7 June doesn't work. What that means is that we're in it and that we need to stay committed and dedicated to solving long-term problems that even our police officers can't solve."

The site where George Floyd was filmed while an officer kneeled on his neck for several minutes

But those efforts have been set back by the city's charter commission, an appointed state body, which determined that the police amendment was too vague, and put off any vote for another year.

In the meantime the council has taken some steps. It diverted $1.1m from the police budget to newly formed community patrols. And Minneapolis has instituted some incremental reforms, such as banning police chokeholds.

But Dave Bicking, a veteran activist against police violence, says the council's radical move has done more harm than good.

"The diversion of that pledge and the city charter amendment I think are steps that took away from the chance to make short-term changes to the behaviour of the police department that would have made a difference," he says, citing in particular investigation of and discipline for incidents of misconduct and excessive force.

In South Minneapolis, another community caught in the line of fire is trying to make its own sense of the city's upheavals.

Ade Alabi has banded together with others in the neighbourhood to try to preserve the diverse and distinctive character of the commercial district around the Third Precinct. In the face of enormous rebuilding costs, they are fighting to keep it in the hands of the community rather than lose it to a handful of corporate property developers.

They too, talk about transformation, hoping to bring more minority business owners into their corner of the city, and create more cultural and social space. It's something that lawyer Daniel Kennedy, who's part of the collective, calls "an opportunity that nobody wanted".

The battered police station sits abandoned on this block of destruction. One option being discussed is to hand it over to the community.

If nothing else, the killing of George Floyd has shifted the conversation about the function of a police force, even as it has starkly exposed how difficult that is to change.

"I don't want to go back to normal," says Meena Natarajan, the owner of a theatre company and another member of the group, "because normal was racist."

- Published29 May 2020

- Published30 July 2020

- Published23 October 2020