Trump impeachment: Why convicting him just got a lot harder

- Published

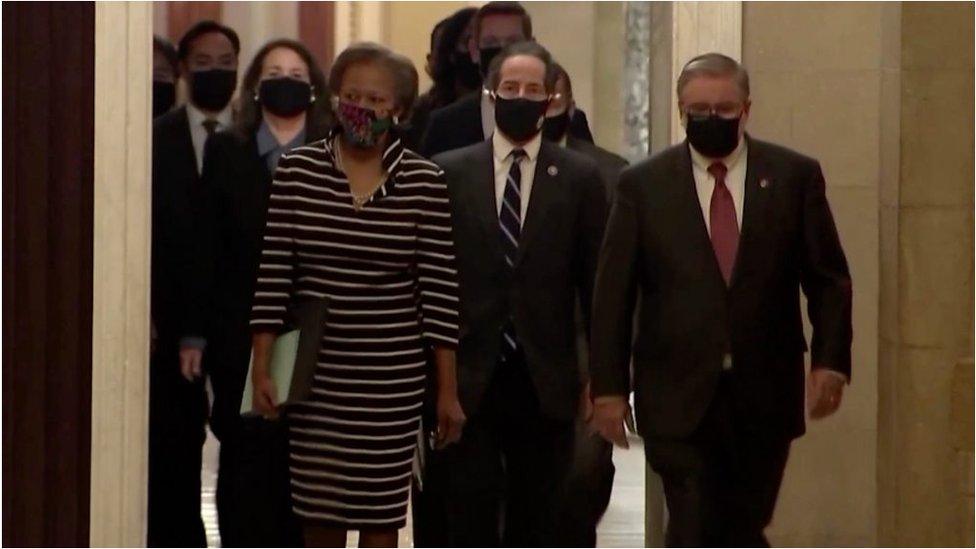

House delivers impeachment charge against Donald Trump to the Senate

Donald Trump left Washington DC almost a week ago, but he continues to cast a long shadow over the Republican Party in Congress.

In the first on-the-record test of support for conviction on impeachment charges that Trump incited his supporters to mount an insurrection at the US Capitol, 45 out of 50 Senate Republicans voted to consider stopping the trial before it even starts.

After the vote Rand Paul, who pushed for the dismissal, crowed that the impeachment article delivered by the House on Monday was "dead on arrival".

He's probably right.

It would take 17 Republican senators breaking ranks and voting alongside the 50 Democrats to convict the president and, with a subsequent up-or-down vote, prevent him from ever running for federal office again.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell was one of 45 Senate Republicans who voted to end the impeachment trial

Tuesday's vote shows there are definitely only five who even want to consider the evidence - Mitt Romney, Lisa Murkowski, Susan Collins, Ben Sasse and Pat Toomey.

The rest contend that presidents can't face impeachment trials once they've left office.

"My vote today to dismiss the article of impeachment is based on the fact that impeachment was designed to remove an officeholder from public office," Senator Shelley Moore Capito of West Virginia said in a statement released after the vote. "The Constitution does not give Congress the power to impeach a private citizen."

Democrats will surely find that a very convenient way of not having to pass judgement on the president's behaviour.

They'll also point out that while there is no historical precedent for such proceedings on the presidential level, a cabinet secretary in the 19th Century faced a Senate impeachment trial on corruption charges even after he resigned from office.

How did Republicans defend Trump - and who voted to impeach?

Regardless of the explanations and justifications, the procedural vote is just the latest, clearest sign of fading Republican support for finding Trump responsible for the Capitol riot three weeks ago.

Shortly after the incident, Lindsey Graham - one of the president's closest allies in the Senate - said the president's actions "were the problem" and that his legacy was "tarnished".

Then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell reportedly was "pleased" with the House's impeachment efforts and said just last week that the mob that attacked the capital was "fed lies" and "provoked" by president.

Both Graham and McConnell voted on Tuesday to move towards ending the impeachment trial.

The Republican Party's evolving views on the president's culpability are probably best captured by the shifting comments of House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy.

During the impeachment debate in the House of Representatives two weeks ago, McCarthy said Trump "bears responsibility for Wednesday's attack by mob rioters" and recommended that he be formally censured by the chamber.

Last week, he said he didn't believe Trump "provoked" the rally and then, a few days later, that "everybody across this country has some responsibility" for creating the political environment that led to the insurrection.

Meanwhile, those who spoke out against the former president and haven't walked back their comments are facing growing calls for political retribution from within their own party.

Liz Cheney, who forcefully criticised the president and was one of 10 Republicans to vote for impeachment in the House, is facing an attempt to remove her from her party leadership post.

Others are being threatened with primary challenges if they run for re-election next year.

Donald Trump may have left the White House, but continues to cast a long shadow over the Republican Party

Following Tuesday's vote, the Senate will go into a holding pattern on the matter for two weeks, while the House impeachment managers and Trump's legal team prepare their cases.

Given the apparent disposition of the Republican senators, the Democrats' only strategy may be to make an acquittal vote, even if it is a fait accompli, as uncomfortable as possible.

They'll do their best to remind the 100 senators of the fear, confusion and anger they felt on 6 January, as they fled the chamber in the face of an angry mob.

They'll try to lay responsibility for the riot at the feet of a president who spent two months questioning the outcome of the election and chose to hold a protest rally within walking distance of the Capitol on the day Congress gathered to certify that election.

And then they'll have to hope that history - and American voters - are willing to assign guilt, even if the Senate isn't.

- Published26 January 2021

- Published19 January 2021

- Published7 January 2021