Covid and school: Three ways US schools are responding

- Published

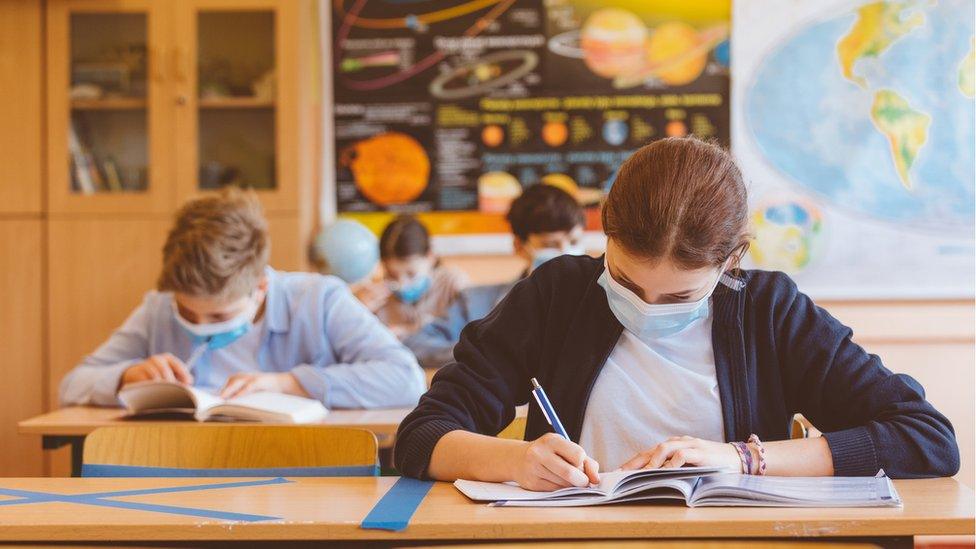

High school prom - stock image

Amid the heated national debate over safely reopening schools, a group of parents in Idaho have planned a high school prom this spring in the absence of a school-organised event.

The Melba School District has welcomed students back to classrooms but has not held major gatherings since the pandemic began.

But social media users spotted flyers on Facebook for a Melba High prom hosted by parents.

The event's tagline reads: 'A little party never killed nobody'.

The prom is Great Gatsby themed, according to one parent, Chanall Astle.

Ms Astle took down the Facebook post after the tagline drew heat on social media but declined to comment on whether the event would be shut down.

"It's hard enough to give our kids some enjoyment this year and let them have a little fun," she told the Idaho Statesman, external. "It's really disappointing as a parent when you try to do a good thing, but people turn it into a bad thing."

A year has passed since schools first closed to slow down the initial spread of Covid-19, prompting concerns over how the pandemic may have stunted academic growth and harmed the mental well-being of students.

The Biden White House announced on Thursday it will soon implement coronavirus testing programmes in schools, but states and local school districts have largely gone it alone so far in planning and funding a return to normalcy.

In Idaho, where the vast majority of public schools are meeting in person, students at Melba Junior/Senior High School have had a regular school year for the most part.

The school's superintendent, Sherry Ann Adams, told the BBC the school improved its cleaning protocols, set up hand sanitiser stations and created smaller working groups at each grade level. She considers the reopening a success because "98% of our enrolled students show up face to face".

But with over 1,900 Idahoans dead from the virus and the governor leaving in place a 50-person limit on public gatherings, the school has gone a year without prom, homecoming and other big events typical of a US school year.

"The reason we aren't doing a prom is we don't want to pick which 50 students from our high school get to attend," said Ms Adams.

When the school principal got word that Melba parents were planning a prom on their own, he gave them a call "to give them the heads up that media outlets had found her announcement" but did not ask for it to be shut down.

"We're really neutral on the situation," said Ms Adams. "We have full confidence in the parents in our community that they're going to make the best decision for their kids."

However, these kinds of decisions may be easier in Melba - a small rural farming community of barely 500 people - than in other parts of the country.

So how are other parts of the US dealing with schools?

Washington DC

In the nation's capital, PTA member Alexandra Simbana says the lack of planning, as well as lack of engagement with parents and teachers, makes her think twice about sending her third grader, Natalie, back.

"Successful reopening makes a lot of assumptions of a pre-existing investment in education, the buildings, the resources, the budgets," said Ms Simbana.

"And if you have a school district that has been under-funded and under-resourced for years, you are further behind on the bare minimum needs for reopening."

"And when the community is mostly comprised of black and brown students and families, they are the ones who will pay a higher price in this pandemic," she added.

About three-quarters of Covid-19 deaths in the District of Columbia have been black residents.

Ms Simbana, who is Ecuadorian American, had her own near-fatal bout with the virus last May, forcing her to spend nine days in hospital, then six weeks on an oxygen tank. She still gets winded climbing the stairs.

"My 20th year teaching - and the most challenging ever"

"I'm barely 41 years old and was having the conversation about what happens when I die because my breathing became so taxing," recounted Ms Simbana.

The ordeal compounded her concerns about reopening schools, she told the BBC, because she believes "people with higher barriers and heavier boats to carry" will be at risk if there is no effective plan in place.

Parents of colour, in particular, have told her "they are terrified that they're going to be forced to return before they are ready".

"You get this wrong and people die," she said.

Portland, Maine

Miles away in Maine, Shay Stewart Bouley shares those sentiments. In a tweet earlier this month, she wrote that she'd rather pull her 15-year-old daughter, MJ, out of school than let her return to the classroom this year.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

MJ's school currently meets in person one afternoon a week and has outlined plans to add one more afternoon. But Ms Bouley and her ex-husband have "chosen to keep her fully remote for the whole school year".

"We have a state where the teachers were not a priority for getting vaccinated," Ms Bouley told the BBC. "And given the state of school buildings and the fact that we know ventilation plays a huge role inside, nothing's changed."

She argued that most organisations - not just schools - had done too little about ventilation to warrant opening back up.

Until MJ, her parents and her teachers are vaccinated, and classes properly ventilated, there is no rush to return, argued Ms Bouley. She admitted that "remote learning has its challenges" but MJ - who deals with anxiety - has been relieved to be home, is doing well academically and is even getting more sleep than she used to get.

"We need to wait until this thing is done," said Ms Bouley.

Related topics

- Published12 March 2021

- Published22 February 2021

- Published27 December 2020