The water fight over the shrinking Colorado River

- Published

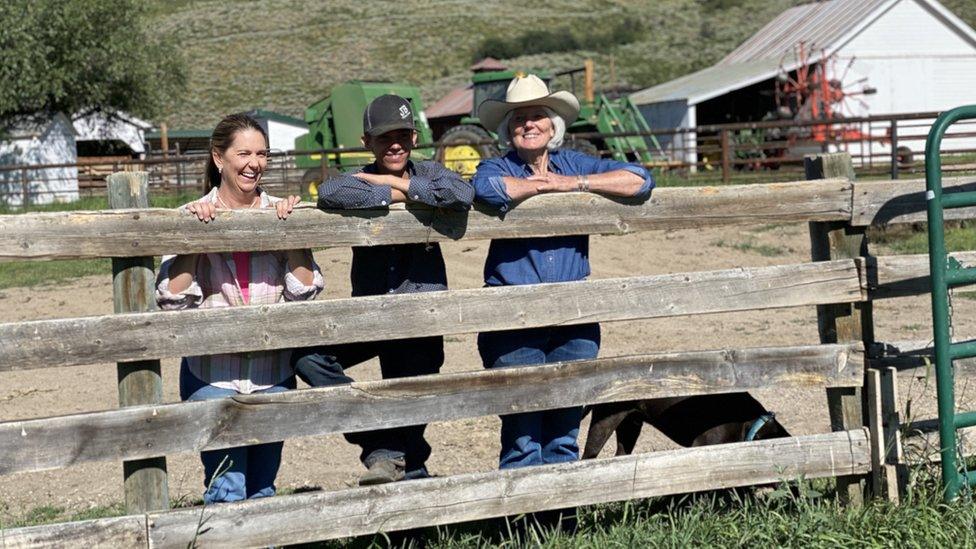

Marsha Daughenbaugh depends on the Colorado River to grow feed for her cattle

Scientists have been predicting for years that the Colorado River would continue to deplete due to global warming and increased water demands, but according to new studies it's looking worse than they thought.

That worries rancher Marsha Daughenbaugh, 68, of Steamboat Springs, who relies on the water from the Colorado River to grow feed for her cattle.

"That water is our lifeblood and without it we would not have the place that we do," says Daughenbaugh, who was raised on this ranch and is hoping to pass it down to her children and the next generation.

"Ranching is not only an economic base for us, it's a way of life."

Three generations of ranchers have grown up relying on water from the Colorado River to support their way of life

But with a two-decade drought in the southwestern US and record-low snowfalls, that lifestyle could be in jeopardy.

"Things seem to be happening even faster than the models or scientists were warning just a few years ago," says Brad Udall, a water and climate scientist at Colorado State University. "If you're not worried about all this, you're not paying attention."

Recent reports show that the river's water flows were down 20% in 2000 and by 2050 that number is estimated to more than double.

This aerial view shows the Colorado River, south of Las Vegas

It's a problem we can't engineer our way out of any longer, Udall says.

"We have massive dams on the Colorado River already. A bigger bank account with less income doesn't do you a whole lot of good," he warns.

Many, like Jim Lochhead, agree there is only one solution - use less water.

"Despite the complexities of how we reach the solutions, the problem is really quite simple. It's a mass balance equation. We have too many demands and not enough water," says Lochhead, CEO of Denver Water, Colorado's largest water utility.

"And so at the end of the day, demands overall will need to be reduced and managed in order to keep the bank account solvent."

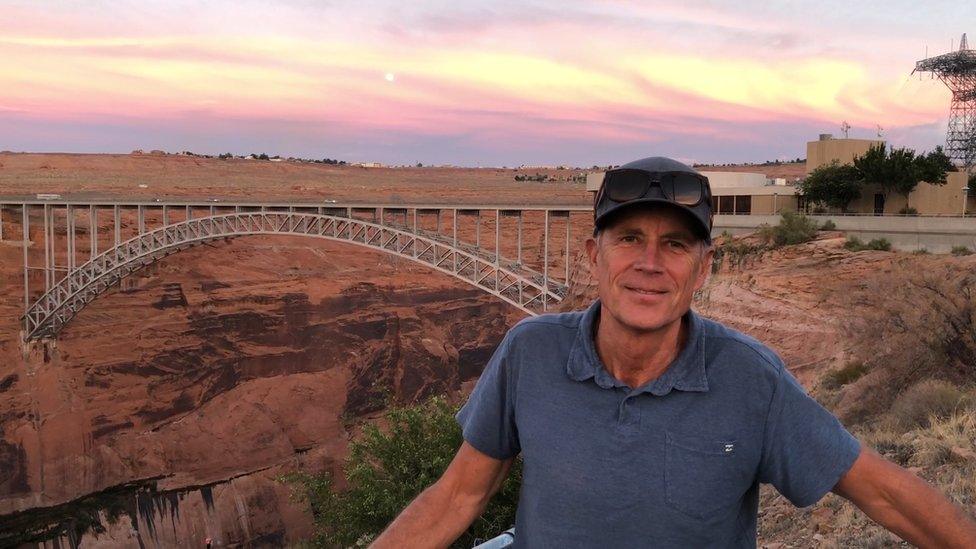

Jim Lochhead says water use needs to go down in order to manage the deficit

But limiting water usage will be tricky.

The Colorado River provides water to more than 40 million people across seven southwestern states, 29 tribal nations and Mexico - and a lot of major cities in those states are heavily dependent on that water.

In Las Vegas, 90% of its water supply comes from the river. In Phoenix and Denver it's 50% and in Los Angeles it's 25%.

According to a 1922 agreement, each of these seven states have a legal right to a certain amount of the river's water. But this compact was made under the assumption that there was more water than there actually was.

Here is what the Colorado River looks like from the Grand Canyon

"On paper we've allocated 30% more water than what's in the river today," says Eric Kuhn, the former General Manager of the Colorado River District.

"And the science suggests that we got a situation where climate change has impacted it even more. The river is probably a third smaller than what was anticipated when the contract was negotiated."

That means officials will have to figure out how to share an amount of water that in reality doesn't exist - and is shrinking.

Another factor in this equation are the various tribes who have legal rights to 20% of the river's water, yet don't have equal access.

Shanna Yazzie of the Navajo Nation is one such example.

Every day, the 39-year-old has to leave her home with buckets to go get water from a local water tank. She's not alone. One-third of the 350,000 residents on the Navajo Indian Reservation don't have running water.

Shanna Yazzie has no running water at home and gets her water from a nearby water tank

"We work, I would say, eight times harder than anybody just to make sure we have water, and pre-planning throughout the day, pre-planning throughout the week. When and where am I going to get water?" says Yazzie.

And during the global pandemic, limited water access has been even more frustrating.

"My kids and myself are all at home, all the time and we are relying on that water more and more each week," Yazzie says. "And when we go to get water we have to ask, is it going to be safe, are there lots of people out there at the water point? There are so many more factors now."

When the 1922 agreement was signed, not a single tribe had a seat at the table. Daryl Vigil, co-director of Water and Tribes in the Colorado River Basin, calls this "the institutional theft of tribal water".

Sadly, Vigil says, this fight for water access is still ongoing.

"Somebody is using tribal water for free and you know once again tribes are not able to utilise that on their own reservations. And what is the impact of those things?" he asks. "Tribes and tribal sovereigns are still 19 times more likely not to have indoor plumbing, I mean in 2021."

While tribes fight for more water access, those in the agricultural community are fighting to keep the water they have.

More than 70% of the Colorado River's flow is consumed by agriculture. But as the river dries, eventually a lot of it will have to leave these communities to sustain cities and suburbs, meaning less water for farmers and ranchers like Marsha Daughenbaugh.

Marsha Daughenbaugh hopes to pass her ranch on to her children

But Daughenbaugh is not naive. She knows there are a lot of competing stakeholders and not enough supply to go around, so collaboration, she says, will be key.

"There are so many diverse interests against this water that we just have to work together regardless of what industry we are coming from," she says.

One of the proposed ideas is to pay farmers and ranchers to use less water to build up reservoirs in times of crisis but at what cost is unclear.

The river's existing management guidelines are set to expire in 2026, meaning these hard questions about conservation can't be put off much longer.

Related topics

- Published21 November 2012

- Published10 August 2015

- Published2 July 2014