How the Bay of Pigs invasion began - and failed - 60 years on

- Published

Sixty years after the Bay of Pigs invasion - the failed attempt to overthrow Fidel Castro's regime in Cuba - the island continues to celebrate its victory while the invaders who survived live on in the US with the satisfaction of having done their duty. BBC Mundo examines the military plan and the reality of what unfolded.

Johnny López de la Cruz feels deprived of air. Locked up in a lorry with more than 100 other prisoners, he can barely breathe.

Inside the vehicle, the detainees are getting desperate. They sweat. Several faint.

Some remove the buckles from their military belt to perforate the car's ceiling and allow some air in. They are buying time. But most expect to be executed as soon as they arrive in Havana.

The vehicle arrives at its destination seven hours later. Military personnel open the doors. Several bodies fall into the asphalt. Nine detainees have died during the trip.

When it is Johnny's turn to exit, he barely manages to jump out.

There are more prisoners besides those arriving in the "lorry of death". In total, spread out across several vehicles, there are nearly 1,100 detainees.

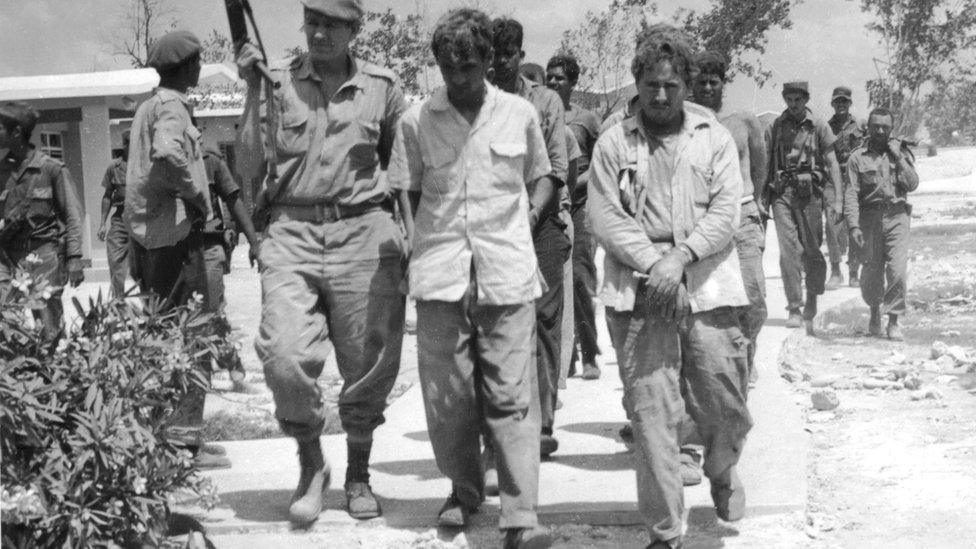

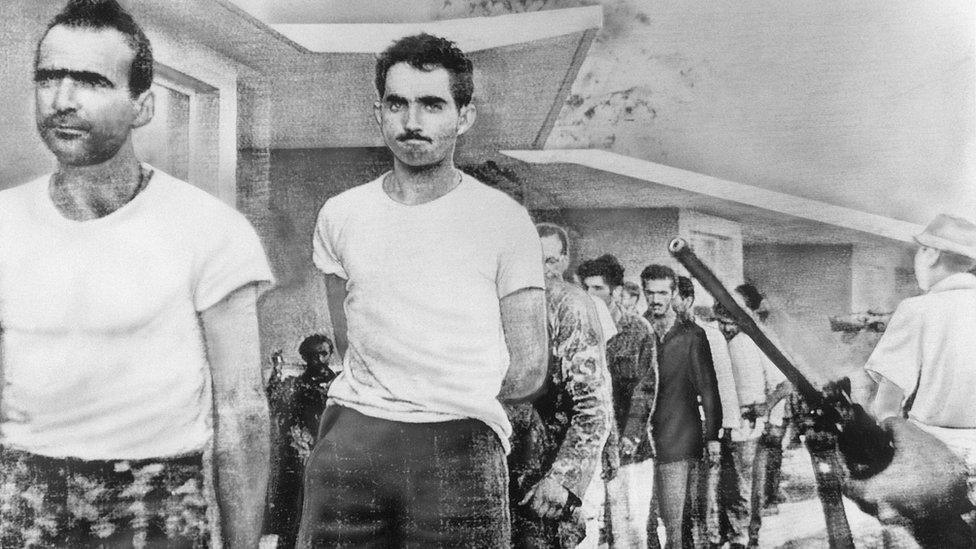

They are the survivors of the 2506 Brigade, an army of 1,400 youths who hours before had failed in their attempt to invade Cuba, crushed at Giron beach by Fidel Castro's forces.

Exhausted, without munition and trapped against the beach. The 2506 Brigade 72 hours after landing on the island.

Most are Cuban exiles who, following Castro's victory, were recruited and trained by the CIA to overthrow the island's revolutionary government.

Fidel Castro had reached power slightly more than two years before, on 1 January 1959, when his forces brought down the government of Fulgencio Batista, whom they accused of being authoritarian and corrupt.

Despite substantial popular support for Castro, many Cubans did not agree with his revolution and left for exile.

The Bay of Pigs invasion of 1961 was doomed to fail even before the first shot was fired. The Brigade still blames Washington.

From the White House, US President John F Kennedy cancelled at the last minute the US air strikes that would have neutralised Castro's aviation.

He did so because he felt the United States could not appear to be behind the invasion. Being seen as such would not only damage its international reputation, but would also give an excuse to the Soviet Union, which at that time was consolidating its position as a key ally of Castro, to respond and provoke an unprecedented nuclear conflict.

Under these circumstances, the attack by the determined but inexperienced youths who dreamed of "liberating Cuba from Castro" lasted less than 72 hours.

Many of the wounds left by the invasion impact political postures in Cuba and the US decades later.

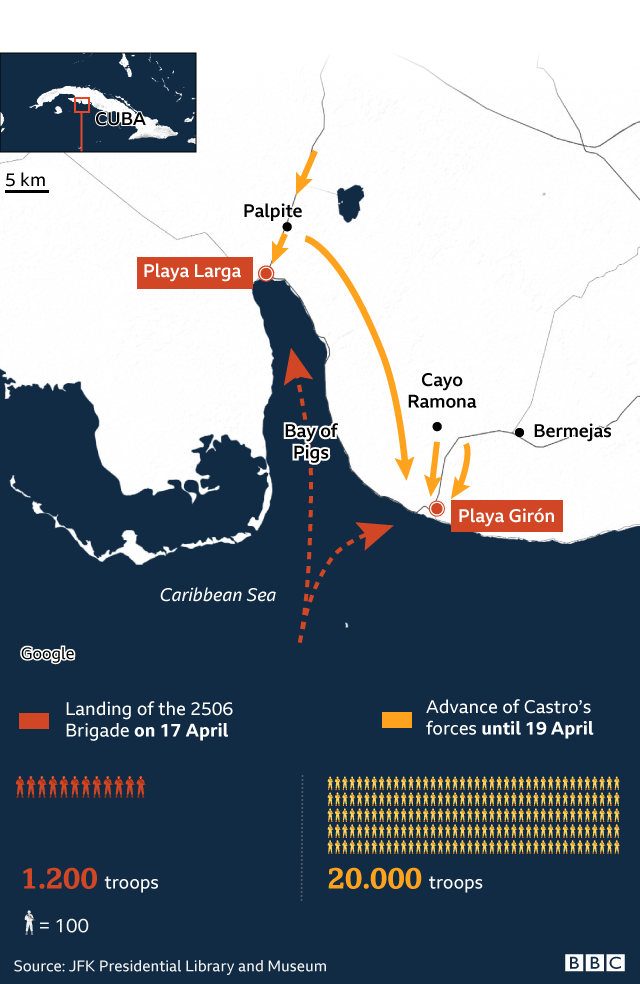

They landed at dawn on 17 April 1961. By the afternoon of 19 April they had already been defeated.

The survivors of the 2506 Brigade were released more than a year later, in late 1962, following intense negotiations.

The surviving members of the invading force are still waiting in exile for the fall of the Cuban socialist government.

Cuba, in turn, commemorates every 19 April the defeat, by a small nation, of an army of "mercenaries" funded by the world's most powerful country.

It has been 60 years.

This is the story of how the invasion plan was hatched, why it failed, and how it has marked the life of its protagonists.

Why I stopped supporting Fidel and joined the invasion

Johnny López de la Cruz, now 80 years old, is the current president of the Association of Veterans of the 2506 Brigade. He was part of a paratrooper battalion that participated in the invasion of the Bay of Pigs. This is his story:

My eyes were opened the day Sergeant Benitez was killed.

He was from Batista's police, a good friend of the family who never left Cuba because he believed he had done nothing wrong.

In the beginning I supported Castro. He never said he was a Communist. If he had done so, nobody in Cuba would have supported that.

But soon afterwards, people started to be executed. Properties and lands were seized and nationalised.

One day, two of Castro's men arrived and took Benitez away to put him on trial. I was there, to support him.

It lasted less than half an hour. He was not even allowed to speak. He and four other men were declared guilty and were taken to an abandoned cemetery outside of town.

They were executed and thrown into a common grave.

I woke up. I did not understand how you could order the execution of people without allowing them to defend themselves. That was an abuse of authority.

Then I started to participate in counter-revolutionary activities.

We would distribute pamphlets and write "Down with Fidel" on walls.

But then, two members of my group were arrested. People close to me told me that I was next. So I went with three friends to Havana and flew out to Miami with fake papers.

When I arrived in the US in 1960 I already knew that other exiles were being trained by the CIA in Guatemala to invade Cuba. I made my way over there a few days later.

Between 1959 and 1960, thousands of anti-Castro youth such as Lopez de la Cruz concluded that their only options were exile or taking up arms against the government.

Most ended up in the US, a country willing to fund Castro's overthrow.

The nationalisation of American industries and businesses as well as Castro's increasing ties with the Soviet Union soon led to a souring of relations between Cuba and the US.

Fidel Castro, surrounded by members of the 26 July Revolutionary Movement, talks about the Cuban Revolution on 4 January 1959

He had become a real threat to the regional influence of the world's most powerful country.

The CIA, the Pentagon and the White House, under the administration of US President Dwight Eisenhower, decided to liquidate the revolutionary leader.

And they found in a group of Cuban exiles the perfect army to execute the plan.

In total, some 1,400 men were recruited.

In the meantime, Cuba adopted preparations as it suspected an imminent invasion.

'Hero of the Fatherland'

Jorge Ortega Delgado fought on Fidel Castro's side during the invasion. When he remembers those days, his eyes sparkle. Sitting down in the porch of his house in Havana, Ortega, who is now 77-years-old, told the BBC how he joined the militias.

I come from a very humble working-class family. When the Revolution triumphed, I was 15 years old and I immediately joined revolutionary activities.

The US started to intervene and to try to attack Cuba. In October 1959 the Revolutionary Militias were founded.

I joined and trained during 1959 and 1960. Towards the end of October 1960, Fidel Castro, the Commander in Chief, arrived at a training session. He asked to talk to all the militias. We were almost 1,500.

He asked those under 20 years of age to join the anti-aircraft artillery forces. That afternoon I asked my parents for permission to go with them. They agreed.

I was sent to Battery Number 30. That was where we started getting trained in anti-aircraft artillery.

The original plan designed by the CIA and the Eisenhower administration was to have the exiles leave from Puerto Cabezas, in Nicaragua, and land near the city of Trinidad, in southern Cuba.

The main objective was to occupy the zone and resist for enough time to establish a rival government by exiled leaders that would later be supported by the United States.

Trinidad is near the Escambray mountain, where there were already members of an anti-Castro group, that would join the invading troops, and, if necessary, would organise a guerrilla warfare campaign similar to the one successfully conducted by Fidel Castro in the Sierra Maestra mountains a few years before.

To facilitate the landing, 16 aircraft would previously bomb Castro's main airports, destroying his air force and gaining advantage over the Cuban skies.

But plans changed radically when Kennedy became President in January 1961. He agreed to continue with the plan, but not under those conditions. He thought that invading Trinidad in broad daylight was too brash.

Kennedy modified the original invasion plan shortly after arriving in the White House in 1961.

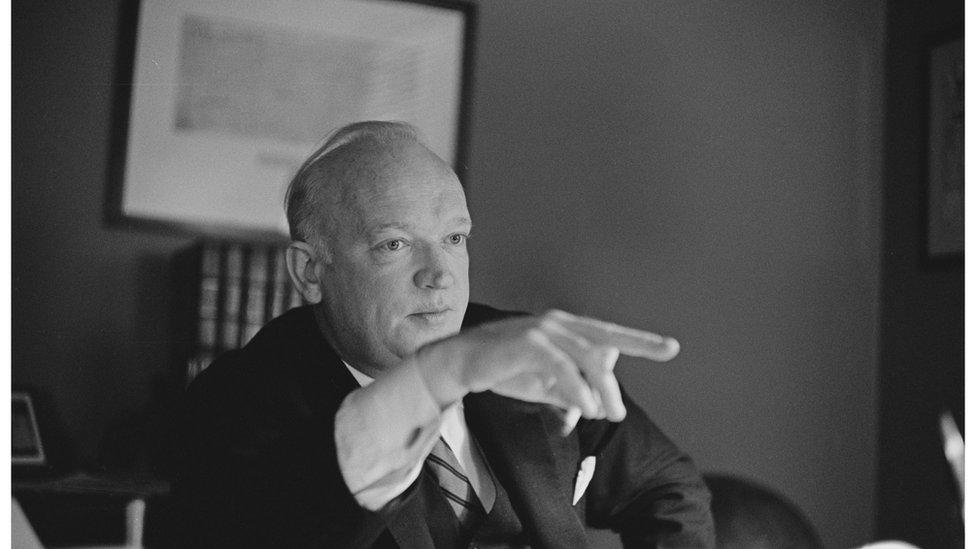

"Kennedy wanted to deny any participation in the invasion. It had to be done covertly. Landing in Trinidad in broad daylight demonstrated too much power, [it would show] that the US was behind", Peter Kornbluh, director of the Cuba Documentation Project at the US National Security Archive.

"The operation had to be as secret as possible and Kennedy gave the CIA three days to re-elaborate a plan that had been under preparation for a whole year", the expert adds. Kornbluh managed to obtain the declassification of a report on the failed military action that remained secret for 37 years.

Kennedy reduced the aircraft from 16 to 8 and urged the CIA to modify the zone and time for the landing.

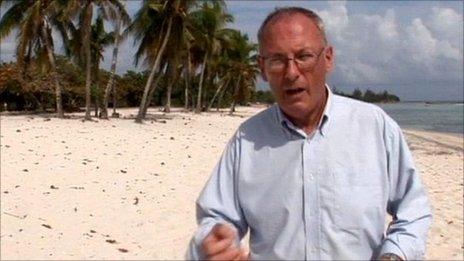

They chose what would later prove to be one of the worst possible sites: the Bay of Pigs, a hard to reach inlet in the south of the island.

In this zone, coastlines are hostile. It is a swampy region with impenetrable mangroves and razor-sharp "dog's teeth", as reefs are known in Cuba. A difficult scenario to carry out a landing with stealth and speed.

Near the Bay of Pigs there was an airport, key for the refuelling of the invaders' aircraft.

Jorge Ortega Delgado completes his first anti-aircraft cannon exercise and anxiously waits to have his day off on 15 April. He has spent several months in military training.

But at daybreak, on that same day, the combat alarm rings. Invading aircraft have bombed two airports in Havana and another one in Santiago.

"We went out immediately. They ordered us to take out the cannon and were deployed to a beach. When we arrived they told us that on daybreak, 15 April, mercenary aircraft had attacked our airfields and killed seven of us", Ortega remembers.

"All of the youth there, we felt very strongly against this. We could not believe it. We were willing to do anything necessary to defend the fatherland", the former combatant says, his voice still ringing with emotion.

The 15 April 1961 bombardment was the first one that Kennedy had authorised to destroy Castro's aircraft before the landing, scheduled for 17 April.

The eight aircraft left on the morning of 15 April from the base at Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, and dropped their bombs over the airfields of Santiago de Cuba, in the country's east, and over Ciudad Libertad and San Antonio de los Banos, both in Havana.

Despite causing seven deaths, they only damaged a few Cuban airplanes, some of them which were already out of service.

Castro's Air Force was left almost untouched and, besides, they managed to shoot down one of the invading aircraft.

After the bombardment, a plane with Cuban insignia landed in Key West, Florida. Its pilot said he was a deserter from Castro's armed forces.

In reality, he was part of the CIA plan to avoid involving the US in the attack.

This way, it would look as if a domestic anti-Castro uprising had started in Cuba, rather than an action promoted by the US.

"But the story about the deserter lasted only a few hours. Although the US denied it, all the world learned that the aircraft were American and that they wanted to pretend that the attack had been executed by Cuban deserters", Kornbluh explains.

With suspicions aroused over US participation, Kennedy cancelled the rest of the air strikes, landing a devastating blow against the objectives of the 2506 Brigade, which was left with insufficient air support.

"I always say that the war was lost before it had begun", Lopez de la Cruz laments.

But at that moment, none of the invaders knew it.

17 April 1961. It is 1:00 in the morning. The invading boats approach Larga beach, at the end of the narrow Bay of Pigs.

They do not want to make noise. Surprise is the key to the plan.

But for months Castro has been suspecting an aggression is coming. He knows that a war against the US is a like a David-Goliath confrontation, and he is well prepared.

"They had militias patrolling practically every beach of the island", Kornbluh explains.

One of these patrols hears noises. They turn on their flashlights and open fire.

The invaders respond. They manage to capture a few of the militias, who have had time to sound the alarm. The surprise factor is gone.

Castro's troops are mobilising to repel the invasion and there are still many invaders waiting to land.

'Paper boats'

Humberto López Saldaña is 83 years old. In 1960 he left Cuba for exile in Miami. Soon after he joined the Brigade. He was in one of the invading boats.

We had a lot of difficulties. We started to fight too soon. This delayed the landing.

Besides, our boats were all too small. Every time they hit one of the reefs they ended up practically destroyed. Many sunk.

The landing continued until early in the morning. We were waiting for the tide to go out to see better and avoid the reefs. From the coast, they threw us a rope to reach land.

At around 6:00 in the morning Castro's aviation appeared. Bombs fell right next to us. Our boats shook like they were made of paper.

The invading boats were damaged as they impacted the reefs in the landing zone.

Soon after a bomb hit my boat, the Houston.

Panic ensued. Several comrades died. The captain threw the Houston against the reefs to help everyone else reach dry land.

Besides disabling the Houston, Castro's aircraft also sunk the Rio Escondido. We had a lot of munition and tonnes of aircraft fuel on those boats. Everything was lost.

'When you start to shoot, you become enraged and you lose fear'

Jorge Ortega and his anti-aircraft battery arrived at the province of Matanzas, where the Bay of Pigs is located, at around 5 pm on 17 April.

There, he found out he would fight against 1,200 men who had managed to disembark in Cuba, besides the paratrooper battalion that had been airdropped in a nearby zone.

Another group of brigade members stayed at the rear guard, without moving.

Ortega remembers hearing the militia men, the sound of tanks and mortar fire.

"On 16 April we had closely listened to Fidel's speech honouring our seven compatriots fallen during the bombardments. On our way to Havana, the people would come out to the street with flags, asking that we defeat the enemy", Ortega remembers.

It was in that speech that Castro declared for the first time the socialist nature of the revolution and he called on the people to repel the mercenaries.

On the morning of 18 April Ortega detected enemy planes. It was the first time he fired a cannon.

"You feel restrained. We all feel afraid. Anyone who tells you otherwise is lying. But you look at the person next to you and you see the rest of the men are firm and resolute. When you start to shoot, you feel enraged and you lose fear", Ortega recalls.

That same day, his battery went in with more troops near Larga beach, laying siege to a substantial part of the exile army.

"On the morning of 19 April we saw how one of the aircraft, shot down by our battery, fell into the sea. Another airplane fell into a sugar cane field. The co-pilot burned to death but the pilot jumped in his parachute and tried to escape. He died in combat with our troops", the ex-combatant tells.

With the cancellation of the air strikes previous to the landing, the B-26 aircraft that accompanied the invasion were easy prey for Castro's practically intact air fleet.

The boats carrying aircraft fuel had been lost and the invading planes could not use the airport near Giron beach, as they had planned.

They now needed to fly four hours round trip to the base in Nicaragua to refuel. Each time they returned to Cuba, they had less than an hour to carry out the bombings.

The crews removed one of the machine guns from the airplanes, to make them lighter. But that left them more vulnerable.

Twenty-four hours after the 17 April landing, the invaders had already lost two of their six ships and half of their air fleet.

Without US air support, the invading B-26 aircraft were more vulnerable.

The rest of the vessels retreated to the open sea, to avoid more damage from Castro's forces.

On 19 April, four American flight instructors based in Nicaragua flew in to support the Brigade members who had been left to themselves. Fidel's forces shot them down.

"They did not have to die, but they felt they had to support us. It was a great gesture", Lopez de La Cruz laments.

Castro knows the enemy is facing difficulties. He orders a full advance to bottle them up against the coastline and prevent them from escaping.

His troops arrive in waves: lorries with more men, armoured carriers, mortars, airplanes.

By the third day, the invaders don't have munitions, aircraft, or escape routes. They surrender at 530 in the afternoon of 19 April.

It is complicated to estimate an exact number of deaths from the invading side.

Castro knew about the difficulties of the enemy and he sent his forces against them at Giron beach.

"There were naval personnel in the boats that sunk and we lost count there", De La Cruz explains.

The president of the Veterans Association calculates that there were 103 deaths and another 100 wounded.

He thinks the casualties were very low, taking into account that the fighting went on for three days.

On Cuba's side, one of the commanders who led the resistance, Jose Ramon Fernandez, said in a book about the invasion he co-authored with Fidel Castro that they had incurred in 176 deaths.

It is hard to estimate an exact number of deaths for the invading force.

An act of arrogance

"The invasion of the Bay of Pigs was a tremendously arrogant miscalculation by the CIA", Kornbluh says.

The intelligence agency's leaders were convinced that Castro's revolution was unpopular and that all that was needed was a military invasion by opponents to spark a popular uprising against him.

"But the truth was that Castro was very popular in that area. He had given them electricity and agricultural aid. The CIA started from false and poor premises to carry out the invasion. Also, it was not that difficult to imagine that tens of thousands of Cuban soldiers would quickly defeat 1,400 invaders", Kornbluh argues.

Some 1,100 men of the 2506 Brigade were captured and sent to prisons in Havana.

Humberto López Saldaña tells BBC Mundo what he experienced after being captured:

Before they sent us to prison, Che Guevara arrived. He asked us what we used to do for a living before leaving Cuba. He seemed very calm, but I always thought that at any moment he could shoot me.

They moved us in several lorries. One of them was too crowded. It was sealed hermetically. Nine of my colleagues died inside that vehicle.

My lorry had its windows open. While we were being moved, people shouted at us in the street: "Mercenaries! Sell-outs! We will execute you!"

Later, in Havana, we were locked up in the Castillo del Principe prison. We were not treated well.

Some prison cells were over-crowded and you had to sleep on the floor

Getting cigarettes was very difficult. Some prisoners resorted to smoking orange peelings.

When we were taken out to walk on the courtyard, a guard would poke us with a bayonet if we did not keep up the pace.

We were around 150 detainees in every prison corridor, but we only had one toilet for all of us.

We were given a cup of coffee that in reality was dirty water. Many times they would spit on it before handing the cup to us. The bread we were given was hard as a rock. They would throw it to the ground. You had to dip it in water to be able to chew it. Food was very scarce.

López de la Cruz spent three months in solitary confinement because he tried to escape and was designated a dangerous prisoner.

Because of that, he was sent in the very last plane that took prisoners back to Miami.

It was Christmas 1962.

Kennedy had sent a famous lawyer to negotiate with Castro.

His name was James B Donovan, who in February 1962 had already facilitated a prisoner exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union.

Relatives of the prisoners and the state prosecutor's office hired the famous lawyer James Donovan to negotiate an exchange.

He went to Havana for the first time on 30 August 1962. On the next day he met with the Cuban leader for four hours.

During the following months, Donovan held several talks with Castro.

Negotiations were approached as a process of "indemnification", rather than as a humanitarian exchange, "something which Castro demanded from the beginning, because he wanted Cuba to be compensated for the expenses of the invasion", Kornbluh explains.

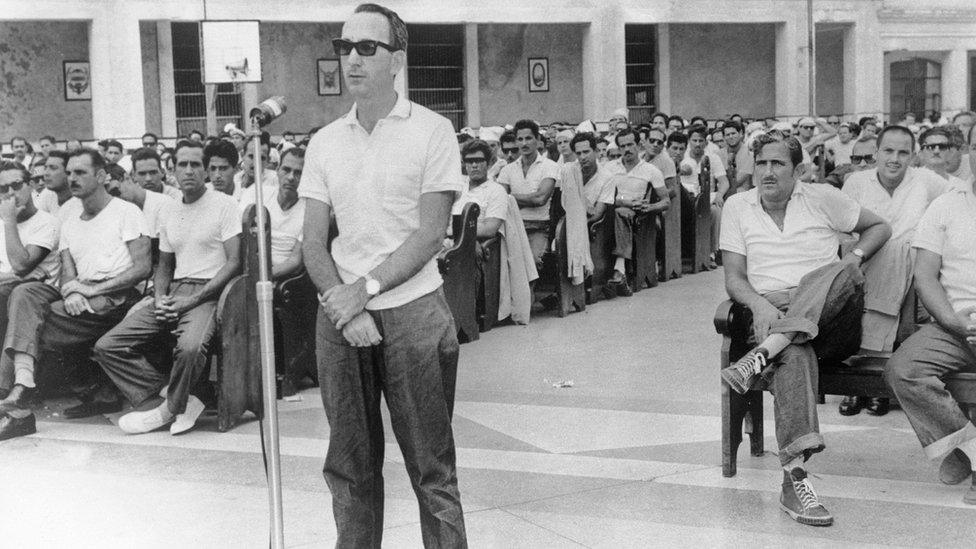

Months before their release, the prisoners had faced a public trial for treason.

Prisoners testified in a televised trial where they described the CIA's involvement in the operation.

Many believed they would end up facing a firing squad, but they were sentenced to 30 years in prison. The court also established that a sum that totalled $62 million US dollars would need to be paid to secure their release.

By the end of December 1962, Donovan agreed with Castro the release of the prisoners in exchange for $53 million US dollars in medicines and food to be distributed among the Cuban people.

As the provisions began arriving in Cuba on 23 December, the first flights from Pan American airlines started to take the prisoners to Miami, where they were met by a welcoming crowd of 10,000 people at the Dinner Key auditorium.

Relatives and friends met the released prisoners in Miami on Christmas, 1962.

In the meantime, Cuba celebrated the "second victory at Giron beach", as they described having won "the battle for indemnification".

Lopez de la Cruz remembers being on the last Pan American flight, looking out of the airplane window and thinking that it would be very difficult to return to his country.

"People say that they exchanged us for cans of baby food, but we did not feel humiliated. Because of our release, Cuba received a lot of clothing, food and medications that the government distributed there", Lopez Saldaña said.

Neither of the two exiles has ever been back to Cuba.

'They will always be enemies of ours'

Jorge Ortega, former Cuban combatant, tells BBC Mundo:

Would I be able one day to sit with one of them and have a drink together? I think it would be very difficult, because of all my comrades who fell or ended up mutilated.

To talk, yes. Cuba is always open to dialogue. But there must be equality of conditions. While there is still a [US trade] embargo, this cannot be.

The people of the Brigade are mercenaries because they sold themselves to a country that hired them. They will always be enemies of ours.

They have never stopped being so. To this day, from Miami, they influence and try to decide, supporting this [US] blockade against our Fatherland.

It is true that [former US President Barack] Obama was in Cuba some time ago and he called for dialogue. But he also called to forget history.

History is never forgotten. We always have it present.

Traitors in Cuba, heroes in Miami

The invasion of the Bay of Pigs is seen in Cuba as an aggression by traitors who sold out to the US.

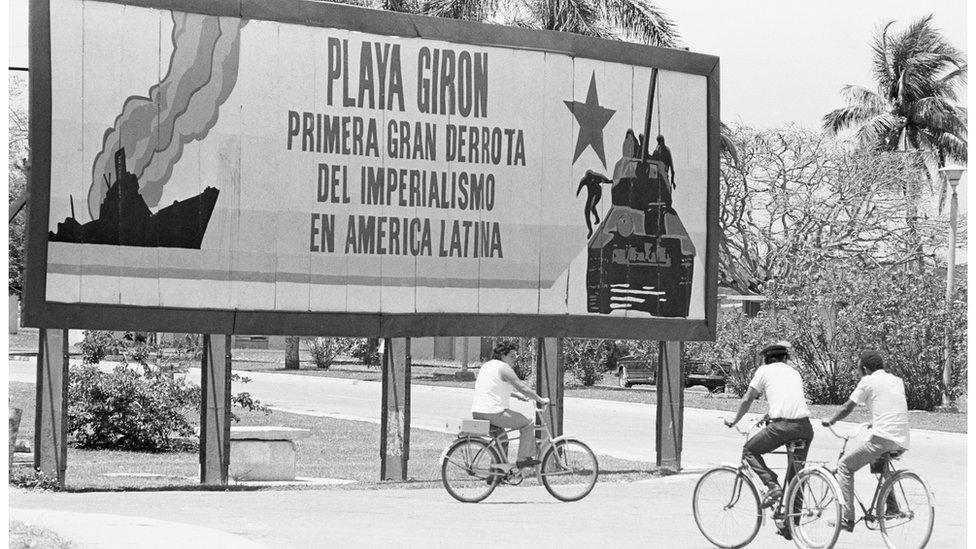

Every 19 April there is a celebration with military parades, commemorating what the Cuban government calls the "first defeat of imperialism in Latin America".

Every April, Cubans in the island celebrate the victory at the Bay of Pigs, as the 'triumph over an army of mercenaries and traitors".

Ninety miles away, however, the feeling is very different.

Nostalgia about what could have been runs through the streets of Miami. Monuments, museums and parks commemorate the heroes of 2506 Brigade.

Today, 60 years later, the survivors don't like to talk about how many Cubans from the other side they killed during the invasion.

"The truth is that I would rather not say. We knew we were going to war, but nobody will ever tell you that we enjoyed killing people. Deep down, we were all brothers", Lopez de la Cruz says.

"You go to kill or be killed. Today it seems different. It is true that we were all Cubans. But at that moment we only thought of liberating Cuba from all the horror that was happening", Lopez Saldaña insists.

The veterans of the Brigade still dream about seeing the fall of the Cuban government in their lifetime.

There are two US presidents whom they find difficult to forgive: Kennedy and Obama.

"Kennedy was not up to it. It was an act of stupidity. Although he wanted to protect the US, it was easy to see that they were involved. Years later, I understand his decision, but the truth is that many people feel betrayed and disappointed for what he did", Lopez de la Cruz tells BBC Mundo.

The veterans are even more critical of Obama.

"He wanted to ingratiate himself with the Castro regime and negotiate, but he was naïve. Cuba opened the doors without changing anything. It was a disastrous policy", Lopez Saldaña insists.

A substantial part of the Cuban exile community in Florida still supports a hard-line policy against the island. They venerate the former brigade members as heroes in exile.

"We have a tremendous satisfaction. We fulfilled our duty even though we did not reach our objective. Here in Miami people respect us a lot. Donald Trump himself met with us several times. In fact, in September 2020 he invited us to the White House. We are very proud", López Saldaña remarks.

Credits

Research and reporting: Jose Carlos Cueto

Editing: Daniel Garcia Marco and Liliet Heredero

Design and illustration: Cecilia Tombesi

Programming: Catherine Hooper

With collaboration from Will Grant, Adam Allen and Sally Morales

Project led by Liliet Heredero and Carol Olona

Related topics

- Published18 December 2019

- Published14 April 2011

- Published27 August 2020

- Published16 November 2019