George Floyd: After a flood of donations, what next?

- Published

The Minnesota Freedom Fund received millions in donations in the wake of the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the ensuing protests worldwide. What happened after?

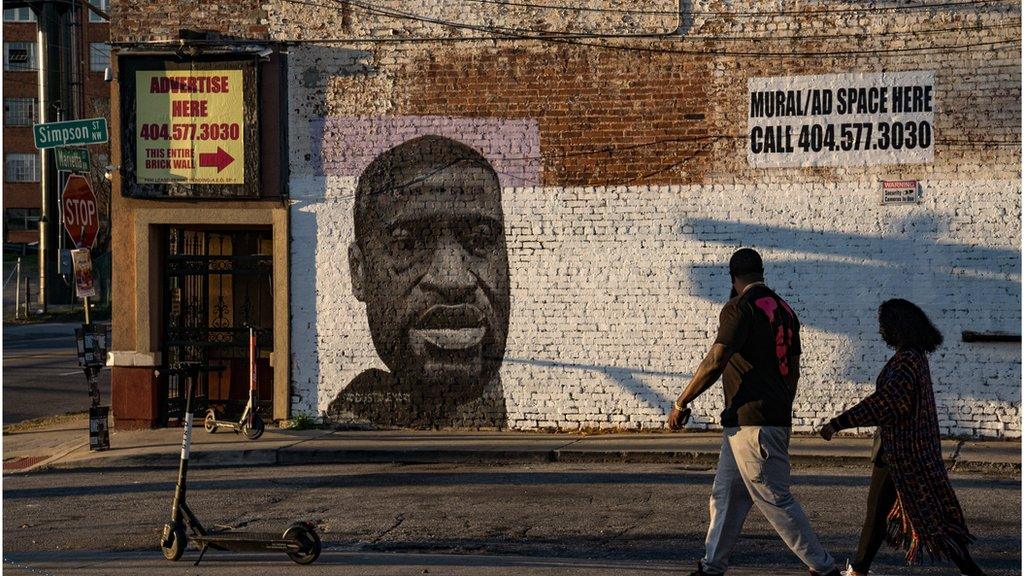

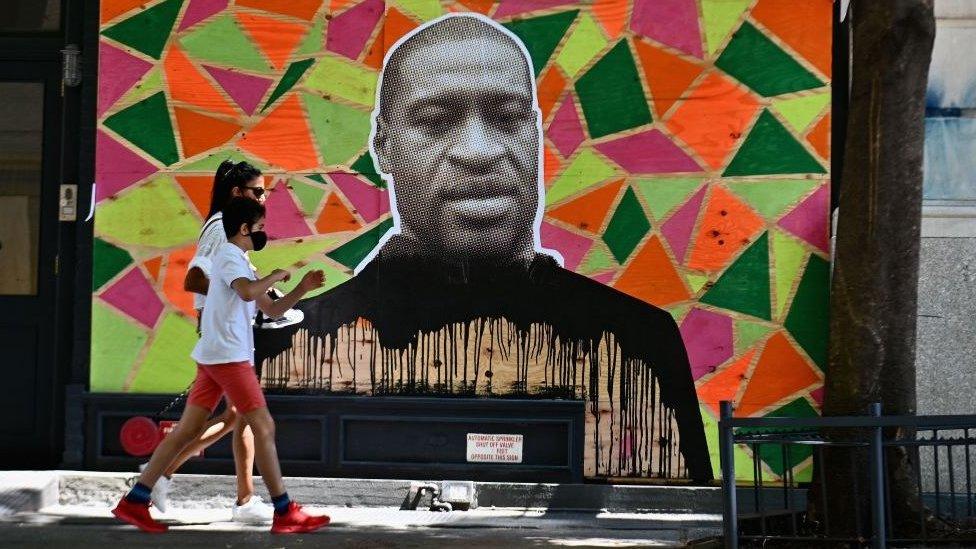

Following George Floyd's death, people globally took to social media to express their anger and pain over the death of an unarmed black man by police.

Posts went viral on Instagram listing local Minnesota organisations where people could donate to help the cause of racial justice.

The Minnesota Freedom Fund (MFF) was one of the organisations mentioned widely online, including by celebrities like Justin Timberlake and Seth Rogan, and public figures like now Vice-President Kamala Harris.

In 2020, the MFF received around $40m (£28.2m) in global donations. They say they've spent around $19m of that so far. But who are they, who has received the money, and who should get the rest?

What is the Minnesota Freedom Fund?

The Minnesota Freedom Fund is a non-profit organisation based in the US state of Minnesota. Their primary mission is to pay the cash bail for people who have been detained by police in a potential criminal case but who have not yet been convicted.

The cash bail they provide allows the person to be released ahead of any scheduled court hearing.

Mirella Ceja-Orozco and Elizer Darris are the co-executive directors of the Minnesota Freedom Fund

Mirella Ceja-Orozco is the co-executive director of MFF. She believes the massive influx of donations came about because the organisation was helping those arrested for protesting the killing of Mr Floyd.

"We were not going to judge whether the person had committed a crime or not because that's what the courts are for," she says.

"But we wanted to ensure that everyone had the dignity that money was not going to be the determining factor whether this person was going to suffer before they were even convicted of a crime."

The MFF says they assist the "most vulnerable members of our community" with their bail fund, including people from black, indigenous and ethnic minority backgrounds, pregnant women, and people who are homeless.

"We're often finding individuals that are detained and held in jail for months on something as little as $70, which is the bail amount, and they don't have that money to pay," she says.

They aim to prevent people being detained for months without a conviction simply because they can't make bail, and the potential damage this might have on their lives when it comes to employment, mental health, and family separation.

As an organisation, Ms Ceja-Orozco says they're a "revolving fund". That means when they pay the cash bail for someone, that money is returned to the organisation when that person appears in court and their case dealt with by the justice system.

The global donations have allowed them to help more people than ever before, they say.

Where did the money go?

So far, the MFF have spent around $19m of the funds it received, the vast majority on local cases in Minnesota.

About $4.5m has gone to the National Bail Fund Network, which is the MFF's umbrella organisation.

Around $1.5m went to a local group of individuals who had been arrested after the protests and then released. They're in the process of setting up their own non-profit called the Minnesota Uprising Arrestee Support group.

One person helped by that support group is Gabriel Mendoza, who attended the protests in May 2020 and who says that after seeing Mr Floyd's death, he felt that "could've been me".

Gabriel Mendoza received assistance from Minnesota Uprising Arrestee Support

Mr Mendoza has been charged with two misdemeanours for damage to property and was in prison for a month. The donations received by the MFF helped him pay his bail and he's now on a two-year probation period.

The money also helped him with fees to pay his lawyer, to pay for the damage caused, for court fees and probation fees.

"The money definitely saved me but the real help was the support, them guys were showing up to my court days, they were there so I felt that," he says.

"They changed everything, they made my spirit a little bit better, they gave me some input and wisdom."

What are the criticisms?

Still, the MFF did received some backlash after the flood of donations. People wanted to know how the millions of dollars were being spent, including some families who have lost loved ones to police use of force.

In August 2019, Kobe Dimock-Heisler was fatally shot by police in Brooklyn Center, Minnesota, after they responded to a mental crisis call. Mr Dimock-Heisler was allegedly threatening his grandfather with a knife.

His mother, Amity Dimock, says her son, who was autistic, "was the most wonderful and loving person" who enjoyed crafts, video games, and horticulture. He also went to culinary school and had ambitions of becoming a chef.

Kobe Dimock-Heisler was shot by police in 2019

She says she's been fighting for justice for her son after no charges were brought against the two police officers involved in the case.

"I hear George Floyd's name coming out of everybody's mouth [like] politicians, professional athletes, actors and actresses, which is wonderful. He deserves all that. But my heartbreak was: 'Why aren't people saying Kobe Heisler?'"

She would like to see more families in situations like hers receive support - and says she would "challenge" groups like MFF and other organisations that received racial justice donations to look at ways to help them directly.

While she says it was "amazing" to see money coming from everywhere in the world for racial justice causes, she questions whether people knew exactly what they were donating to.

She says: "Do they think some of their money somehow gets to any of the actual family members of murder victims? Because if they think that, none of it did."

She says families like hers need support with legal fees to challenge the outcomes of their cases. But she also says, "the most important thing that some of us are trying to do is to create a legacy foundation for our loved ones".

Amity wants to open a non-profit retreat for family members of victims of police violence and for families with children on the autism spectrum.

And she's not the only one who says they are still fighting for justice for their loved one.

In September 2019, Ashley Quiñones lost her husband Brian Quiñones in a police-involved shooting. The following month she set up a non-profit network called the Justice Squad.

Ashley Quiñones lost her husband Brian Quiñones in 2019

In her work for the non-profit, Ms Quiñones has travelled to over 17 states protesting and supporting families going through similar struggles to hers.

"I feel like a lot of people don't realise that our families are living the trial that everyone watched on TV, but behind closed doors," she says.

"It was really hard for our family; we didn't have anybody showing up. We had maybe 10 people, sometimes less, at a protest."

None of the officers involved in her husband's case have been charged with his death.

Ms Quiñones started the Justice Squad to help families with things she felt she didn't have help with when she lost her husband.

"The stress of this is not a joke," she says.

"What happened to me, that was my husband, that's my head of household. He carried mine and my son's insurance. He paid for the bills. My parenting didn't get to stop because they killed my husband, my bills didn't stop because they killed my husband."

She is in the process of a civil case. She's been working on petitions, policy change, and education within the community.

What happens next?

Ms Ceja-Orozco says the criticisms people have around the MFF and the money they received are "valid".

She says, "I want our organisation to be held accountable to the community. However, because of the type of organisation that we are, it's also a need to protect the individuals that we're helping."

Recently, the MFF say they have reached out to several organisations dealing with family members of people who have been harmed by police actions and have begun early conversations.

They have also posted details on their site directing people on how they can donate to organisations that work directly with families like Ms Quiñones' and Ms Dimock's.

Meanwhile, the two women are continuing to fight to get answers for what happened to their loved ones.

They say there's more work to be done - but they remain hopeful of cultural shift towards racial justice.

Related topics

- Published28 May 2021

- Published26 May 2021

- Published7 May 2021

- Published16 July 2020

- Published12 March 2021