Daniel Ellsberg: The 90-year-old whistleblower tempting prosecution

- Published

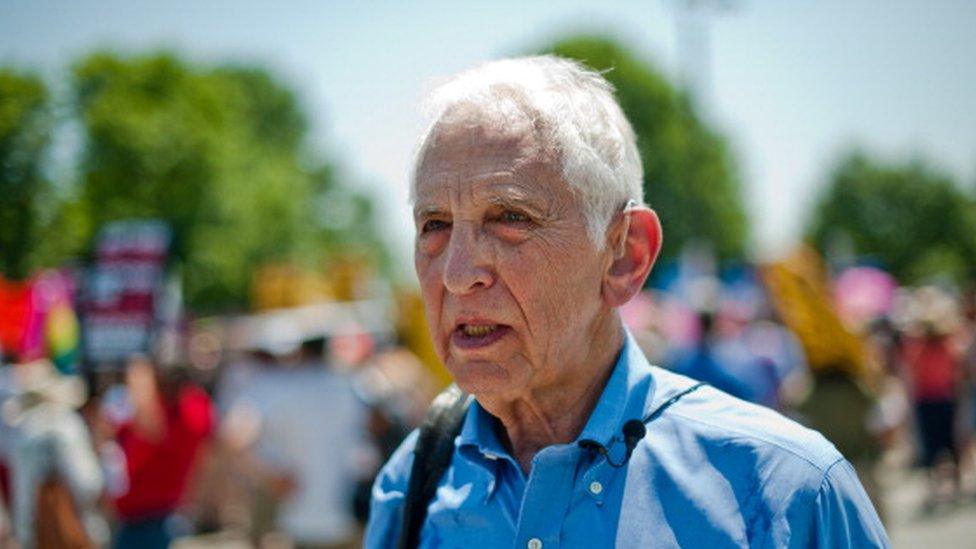

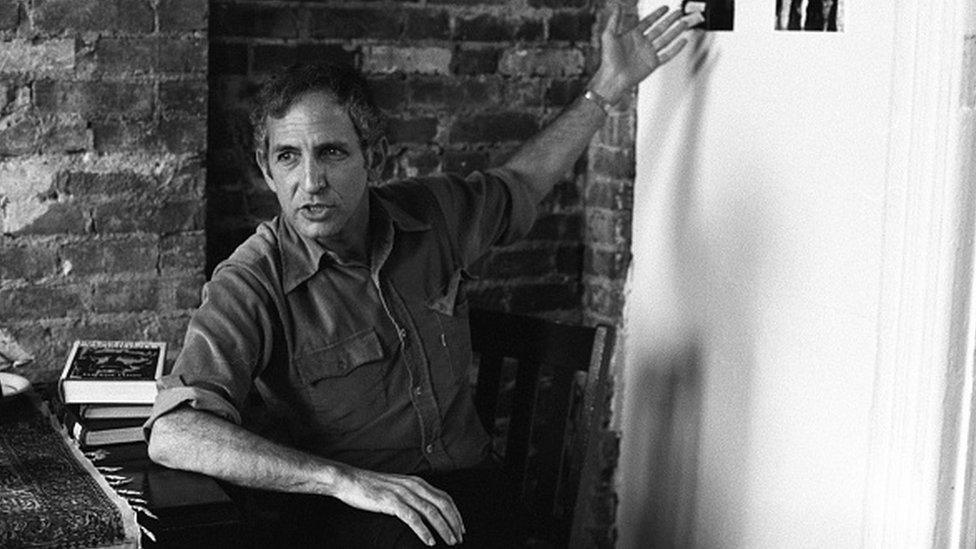

Daniel Ellsberg has warned against the dangers of nuclear weapons and military interventions for decades

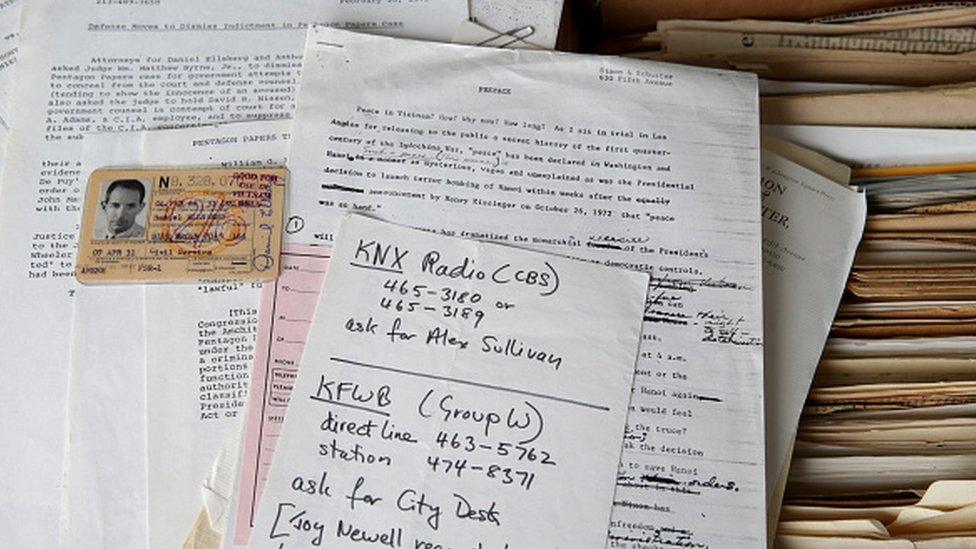

A tedious but consequential task kept Daniel Ellsberg busy for weeks from the end of 1969.

One by one, he photocopied thousands of top-secret documents that he hoped would end a long and costly conflict.

Known as the Pentagon Papers, the documents were part of a classified study that showed the extent of American involvement in the Vietnam War.

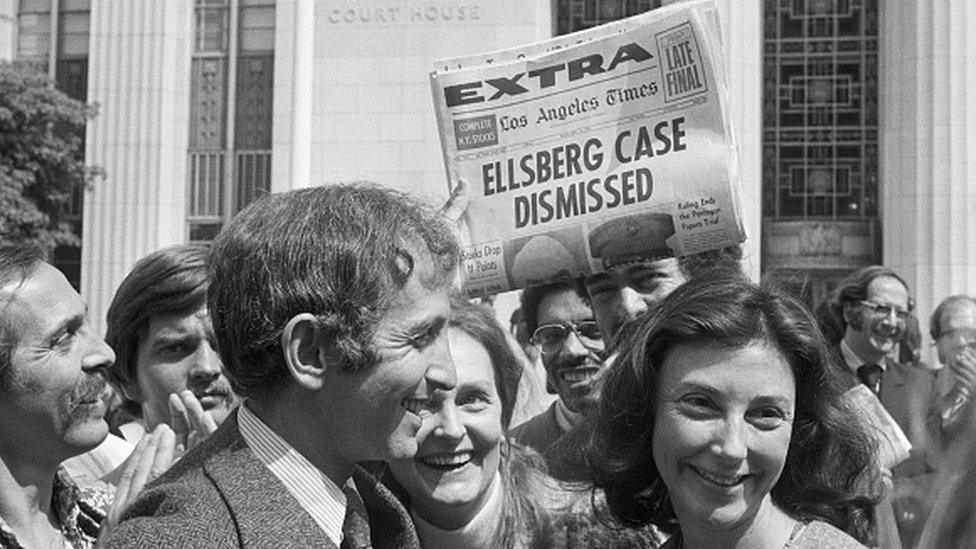

Mr Ellsberg famously leaked the study to newspapers in 1971 before facing espionage charges that were ultimately dismissed.

While the Pentagon Papers left a lasting legacy, they weren't the only documents Mr Ellsberg got his hands on.

At the same time, Mr Ellsberg copied another classified study that showed how seriously American military chiefs took the threat of nuclear war during the Taiwan crisis of 1958.

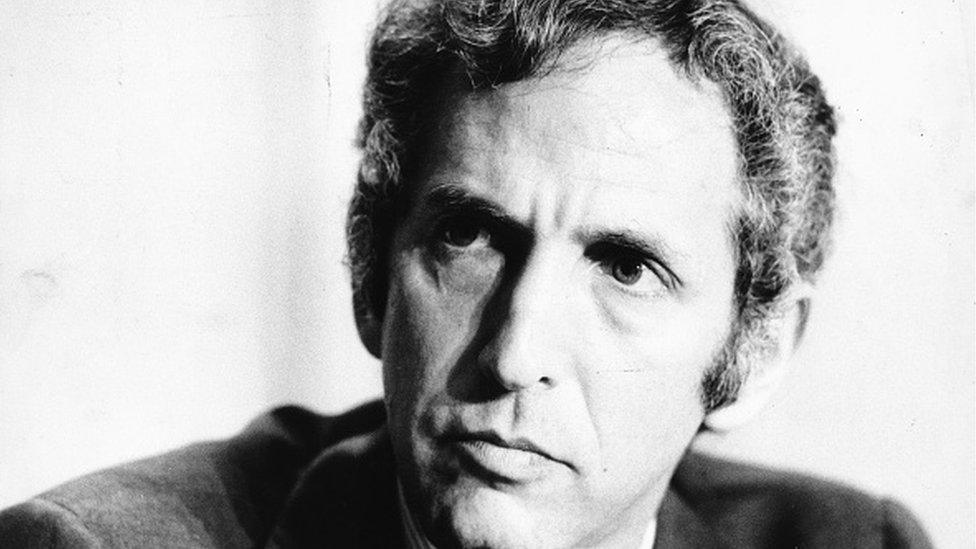

Daniel Ellsberg leaked the Pentagon Papers to expose actions the US had taken in the Vietnam War

For 50 years, the study went virtually unnoticed until 2017, when Mr Ellsberg published the full document online, which was highlighted by the New York Times newspaper last month, external.

In theory, Mr Ellsberg's disclosure could put him at risk of prosecution on the same charges he faced for leaking the Pentagon Papers.

Now aged 90, Mr Ellsberg says he is not intimidated by the possibility of prison. In an interview with the BBC, he explained why.

For decades, Mr Ellsberg has been a tireless critic of government overreach and military interventions. His opposition crystallised during the 1960s, when he advised the White House on nuclear strategy and assessed the Vietnam War for the Department of Defense.

What Mr Ellsberg learned during that period weighed heavily on his conscience. If only the public knew, he thought, political pressure to end the war might prove irresistible.

The release of the Pentagon Papers was a product of that rationale, which underpins Mr Ellsberg's latest disclosure, albeit in a different context.

Mr Ellsberg photocopied 7,000 pages of the classified study on the Vietnam War

"I want to do my part in avoiding nuclear war," Mr Ellsberg said from his home in California.

In his assessment, a nuclear war over Taiwan is a serious threat. To understand why, consider the unsettled question of Taiwan's relationship to China.

China has asserted sovereignty over Taiwan since the end of the Chinese civil war in 1949. Since then, China has regarded Taiwan as a rebel province that must be reunited with the mainland - by force if necessary.

As Taiwan's most-important ally, the US would be expected to take action if China did attack the island.

"Taiwan is a war-and-peace issue for China"

"War games appear to show that the Chinese would win a conventional war over Taiwan and against the US," Mr Ellsberg said. "That would immediately raise the question of the US initiating nuclear war against China to prevail in that situation, just as US decision-makers committed themselves to doing if it was necessary in 1958."

In the end, it was not necessary in 1958. But what material released by Mr Ellsberg shows, in sobering detail, is why American military leaders believed it might have been.

That material amounts to dozens of redacted pages from a study of the crisis of 1958, when Communist Chinese forces began shelling islands controlled by Taiwan's nationalist government.

Dated 1966, the study was written by Morton Halperin for the Rand Corporation, a government-funded think tank, before being declassified in 1975 with portions removed.

In one censored passage, the study suggests senior military leaders, including Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman General Nathan Twining, "felt that the use of atomic weapons was inevitable".

The Taiwan crisis of 1958 lasted for four weeks from the end of August

Another section suggests Twinning indicated the US "would have no alternative but to conduct nuclear strikes deep into China" if it did not cease its attacks on Taiwan.

When Communist Chinese bombardments abated, none of this came to pass.

Still, highlighting this episode does serve an important objective, said Professor Steve Tsang, director of the China Institute at SOAS University of London. He told the BBC the risk of a military confrontation over Taiwan will become greater as China develops "the right kind of capabilities" in terms of weaponry.

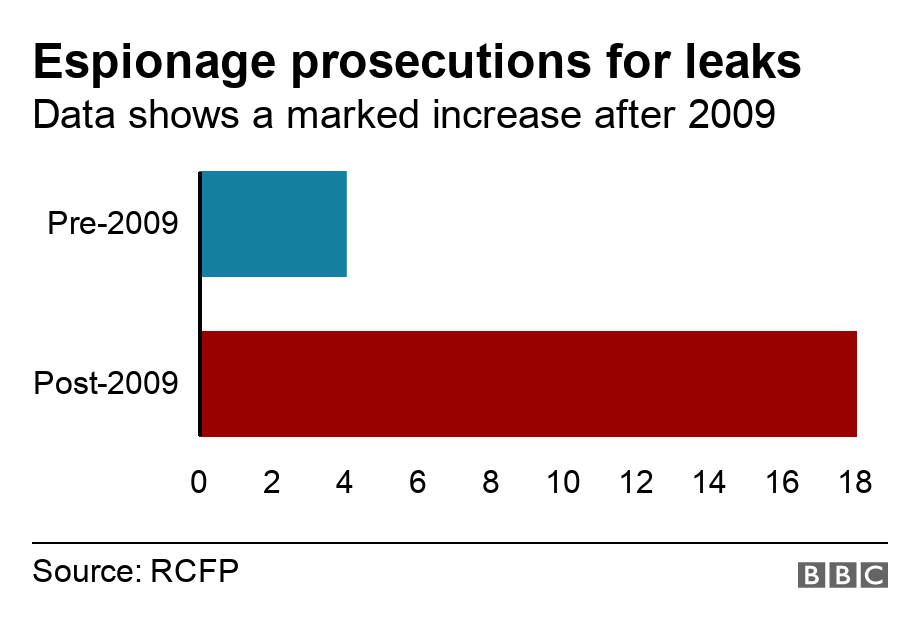

In exposing this risk via his leak, Mr Ellsberg said he faced the possibility of prosecution under the Espionage Act.

Designed to suppress dissent, the law was enacted in 1917 during World War One.

Reflecting the security concerns of the time, the act outlawed the unauthorised disclosure of information intended to damage the US or benefit an enemy. Over time, its restrictions on free speech under the First Amendment of the US Constitution prompted precedent-setting legal challenges.

Wikileaks founder Julian Assange, pictured here (L) with Mr Ellsberg (R), has been charged under the Espionage Act

An early case concerned socialist Charles T Schenck, whose conviction for distributing flyers opposing the military draft was upheld by the Supreme Court in 1919.

In more recent years, CIA consultant Edward Snowden, US Army intelligence analyst Chelsea Manning, and Wikileaks founder Julian Assange have been charged with violating the act.

Their prosecutions represent an escalation in a whistleblower clampdown that can be traced back to Mr Ellsberg in 1971. While he was acquitted because of governmental misconduct, others have not been so fortunate.

They, like Mr Ellsberg, had limited scope to defend themselves in court.

For government officials who give classified information to the press, "their hands are often tied", said Trevor Timm, executive director of the Freedom of the Press Foundation.

"It doesn't matter whether what you revealed was illegal conduct by the government," Mr Timm told the BBC. "All of this is deemed irrelevant in court. So it means there really is no defence."

At his trial, Mr Ellsberg was not able to argue that he leaked the Pentagon Papers in the public interest. This argument was irrelevant, the judge ruled, because the act provides no such defence, which is often invoked by journalists.

Without that defence, Mr Ellsberg said, government whistleblowers like him "can't get a fair trial". To avoid long jail terms, most defendants strike plea deals, thus waiving their right to appeal.

"I want to change that. We need more whistleblowers, not fewer," Mr Ellsberg said.

The espionage charges against Mr Ellsberg were dismissed in 1973

If he were to be prosecuted for a second time, Mr Ellsberg would take a different approach. There would be no plea bargains, no shadow boxing with the White House.

This time, Mr Ellsberg wants his day in court.

"The First Amendment guarantees the freedom of the press," he said. "This should rule out the use of the Espionage Act. If I'm found guilty on the precedent of previous cases, I think it should go to the Supreme Court."

This would be uncharted territory for the Department of Justice, whose use of the Espionage Act to prosecute leakers has never been addressed by the Supreme Court.

Given this, Mr Ellsberg said the administration of US President Joe Biden would "be reluctant to bring this case against me", because it would bring attention to the unauthorised disclosure of classified material by a 90-year-old.

"I don't think they would like to test that in court. They have a real chance of losing," he said.

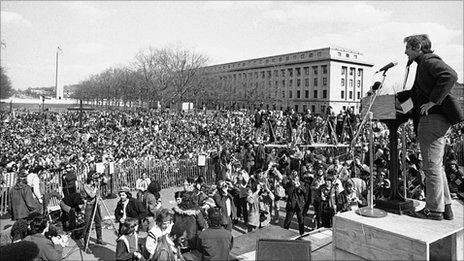

Mr Ellsberg has been a long-time critic of the government's use of the Espionage Act

So far, appeals against Espionage Act convictions of this kind have fallen short in lower courts.

Noting this, Mr Timm said he expected an "uphill battle" for anybody who sought to challenge the constitutionality of prosecutions under the act, even if some Supreme Court justices were sympathetic to free-speech arguments.

Should he end up fighting this battle, Mr Ellsberg has already made peace with the hazards of exposing state secrets.

Even at the age of 90, some things are worth making sacrifices for, Mr Ellsberg said.

"That's how I felt in 1971, so I made that calculation a long time ago," he said. "Preventing a war and stopping constitutional abuses are of course worth risking prison."

Related topics

- Published13 June 2011

- Published10 June 2013

- Published7 December 2017