Why cannabis is still a banned Olympics substance

- Published

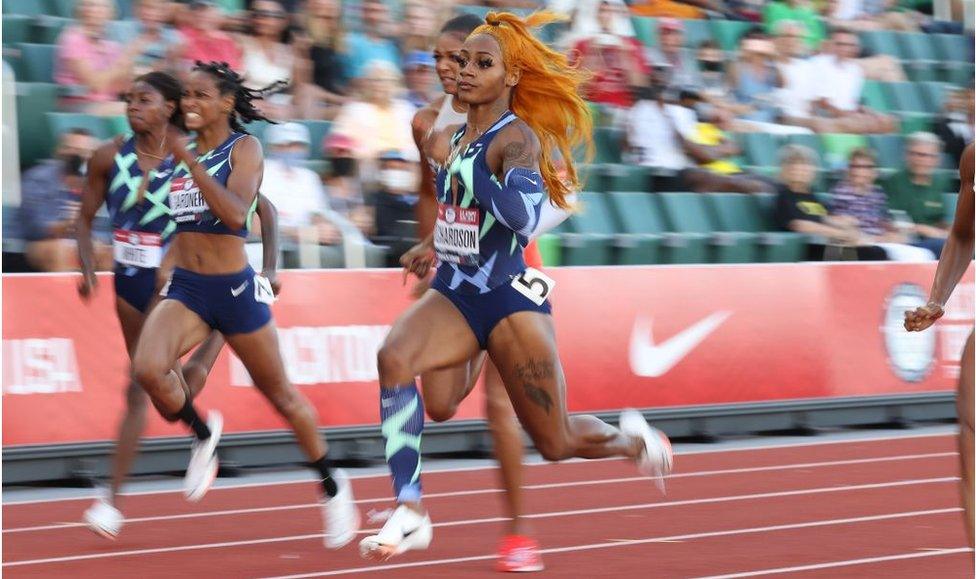

Sha'Carri Richardson was banned for cannabis use, despite winning the US trials for her event

US sprinter Sha'Carri Richardson will be missing the Tokyo Olympics because she tested positive for marijuana during the US Track & Field trials. With cannabis legal in many states across America, why is it still outlawed in sports?

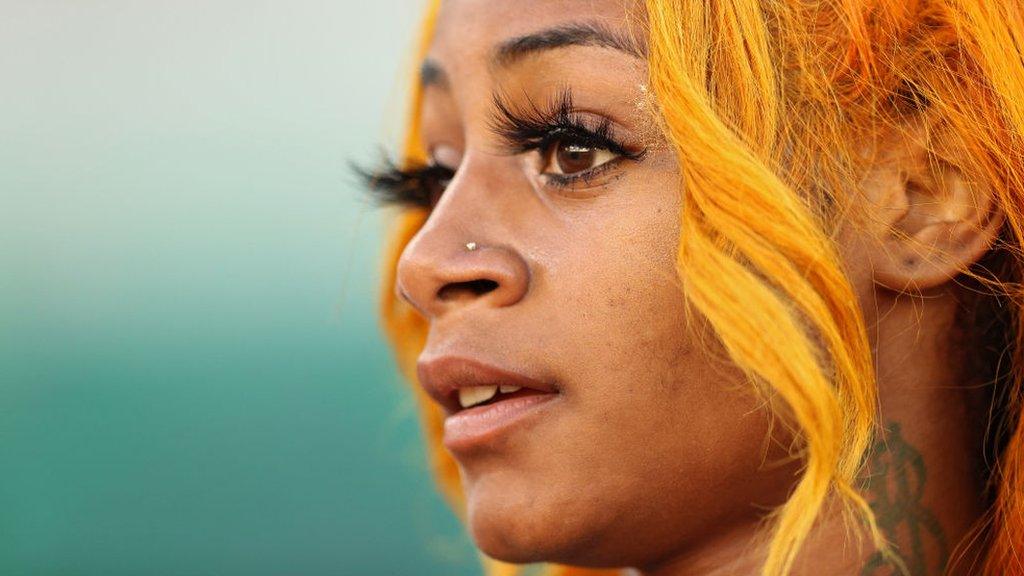

With her flowing tangerine orange hair, killer smile and lightning speed, Sha'Carri Richardson was unmissable in the lead-up to the Olympic Games.

Considered the sixth-fastest woman in history, with a best-ever time for the 100m of 10.72, the Texas sprinter was expected to be a major contender for the Gold medal in Tokyo.

But when her teammates take to the track for the women's 100m heats on Friday, she won't be there.

In early July, it was announced that Ms Richardson would not be representing the US at the games because she had tested positive for cannabis use during the qualifying race.

As punishment, the US Anti-Doping Agency banned her from competing for one month and expunged her qualifying victory. Although the 30-day suspension technically ended during the Tokyo games, US Athletics chose not to include her on the team.

Her disqualification has reignited a long debate over marijuana prohibition in Olympic sports.

Joggers in Colorado run in support of Richardson

Given that it is legal in many US states, and that its performance-enhancing properties are disputed, many wonder why cannabis should still be banned.

A 'performance enhancing' substance?

Marijuana (cannabis) has been banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) since the organisation first created its list of prohibited substances in 2004. Items on the list meet two out of three criteria:

Criteria 1: They harm the health of the athlete

Criteria 2: They are performance enhancing

Criteria 3: They are against the spirit of sport

It is the second point that people seem to take the most issue with when it comes to weed, and it has become the subject of many late-night punchlines.

"The only way it's a performance-enhancing drug is if there's a big [expletive] Hershey bar at the end of the run," joked the late comedian Robin Williams.

In 2011, Wada defended the ban on cannabis in a paper published in the journal Sports Medicine. Citing a study on marijuana's ability to reduce anxiety, Wada found cannabis could help athletes "better perform under pressure and to alleviate stress experienced before and during competition".

Sha'carri Richardson

But those findings aren't enough to warrant concluding marijuana is a performance-enhancing drug, argues Alain Steve Comtois, director of the department of sports science at the University of Quebec at Montreal.

"You have to take the big picture," he tells the BBC. "Yes anxiety levels go down, but in terms of actual physiological data, it shows that performance is reduced."

Mr Comtois was one of the authors of a 2021 Journal of Sports Medicine and Physical Fitness review of research on marijuana use before exercise and its capacity to enhance athletic performance.

The paper found that most research points to marijuana hindering physiological responses necessary for high performance, by raising blood pressure and decreasing strength and balance.

The paper did not look at the effects of marijuana on anxiety, but Mr Comtois says its other negative effects would counteract any benefits, giving the idea that marijuana can enhance athletic performance "no merit".

Marijuana enthusiasts run in the third annual 420 Games in San Francisco in 2016

Drugs and the spirit of sport

But there is more to Wada's rule than just a ban on performance-enhancing drugs.

Founded in 1999 after several high-profile doping scandals at the Olympics, Wada aimed to lead the charge to end doping in sports around the globe. When coming up with its list of banned substances in 2004, marijuana was illegal in almost every country in the world.

"They didn't want to get in social respectability trouble," says John Hoberman, a cultural historian who researches the history of anti-doping at the University of Texas-Austin.

Its status as an illicit drug was cited by Wada in the 2011 paper as one of the reasons why marijuana offended the "spirit of sport" (criteria 3) and was "not consistent with the athlete as a role model for young people around the world".

The rule has led to reprimands for not only Ms Richardson, but also dozens of other athletes.

In 2009, Michael Phelps was banned from competition for three months, and lost his Kellogg's sponsorship, after photos of him smoking marijuana were leaked online, external.

Phelps has won 28 Olympic medals

US sprinter John Capel was banned for two years after testing positive for a second time in 2006.

Before Wada created the prohibited drug list, the International Olympic Committee tried to take away Canadian snowboarder Ross Rebagliati's gold medal because he tested positive.

It was returned after a court ruled there was no official rule against it - the IOC banned it two months later.

But over the past decade, marijuana's legal status - and society's attitude towards it - has begun to shift.

Uruguay was the first to make it legal to buy and sell marijuana for recreational use in 2013, with Canada following suit in 2018.

Many more countries have decriminalised it to a some degree, including South Africa, Australia, Spain and the Netherlands.

In the US, it is illegal federally, but it is legal in about a third of states - including the state of Oregon where Ms Richardson tested positive.

Tourists browse a marijuana shop in Los Angeles

There has also been an increasing acceptance of cannabis use for medical purposes, with many countries, including the UK, allowing medical marijuana.

In fact, in 2019, Wada removed cannabidiol (CBD), a component of cannabis, from the banned list, even though the chemical remains illegal in some countries, like Japan, where the Olympics are hosted this year.

These changes have fuelled the current criticism of Ms Richardson's ban.

The runner told NBC News that she had used marijuana to cope with the death of her mother a week before the qualifier.

"I greatly apologise if I let you guys down - and I did. This will be the last time the US comes home without a gold in the 100m," she said.

Amid an outpour of sympathy for Ms Richardson, Wada faced a dilemma. As Mr Hoberman puts it: "You can't run an organisation that is rules bound, and simply dissolve a rule at a convenient moment".

Because the cannabis ban is still on the books, an exception could not be easily made for Ms Richardson.

"And so this young woman was victimised by the existence of this rule," says Mr Hoberman.

What next?

It's unclear if or when Wada will reconsider the ban on cannabis but pressure is mounting for it to do so.

Cannabis boom: Why Oklahoma is a 'wild wild west'

Ms Richardson's suspension prompted US President Joe Biden to question the current law, although he fell short of saying it should be overturned, prompting rumours the White House could step in.

"Rules are the rules. Everybody knows what the rules are going in," Biden told reporters Saturday in Michigan. "Whether they should remain that way, whether that should remain the rule, is a different issue."

Even the United States Anti-doping Agency, the American authority that enforces Wada's rules, said "it's time to revisit the issue."

Until then, Ms Richardson, and other athletes like her, will have to stay away from cannabis, or stay on the sidelines.

Related topics

- Attribution

- Published2 July 2021

- Attribution

- Published23 June 2021

- Published26 March 2021

- Attribution

- Published29 December 2021