From Afghan interpreter to US homeless - the long road to the American dream

- Published

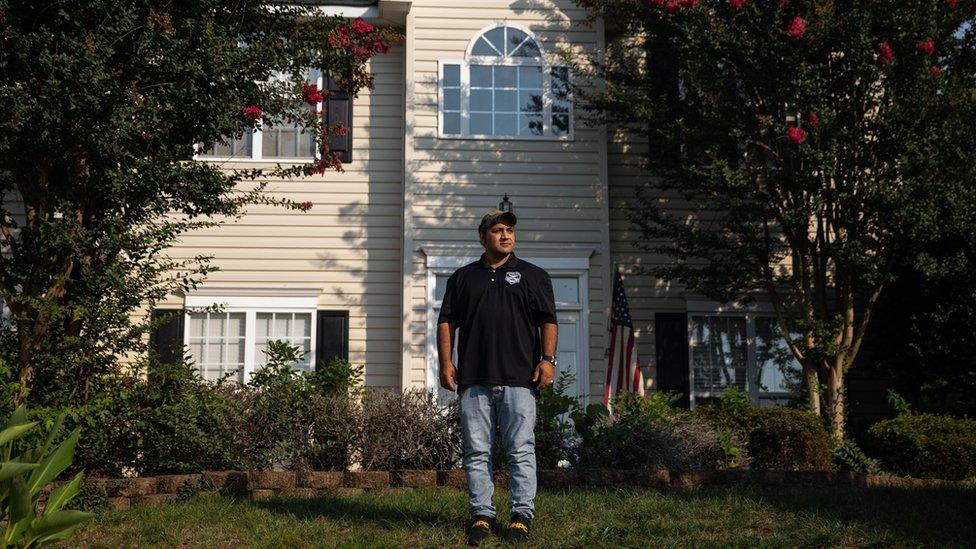

Zia made it to the US with his family in 2014 after a six-year wait

Zia Ghafoori, his pregnant wife and their three small children landed in the United States from their home in Kabul in September 2014.

He held five US visas - a reward for 14 years of service as an interpreter with US Special Forces in Afghanistan.

But the benefits stopped there. Upon arrival, Zia found himself homeless - sent to a shelter by a well-meaning volunteer who told him it would be a place for him and his family to start a new life.

Seven years later, the memory still angers him.

Speaking to the BBC from North Carolina, where he now lives, he recalled struggling to look his children in the eye, apologising for bringing them to the US.

"I couldn't control my tears," he said. "After what I had done for both countries, I was asking myself 'is this what I deserve?'"

But among his peers Zia, now 37, counts himself lucky to have made it to the US at all.

Tens of thousands of Afghans have served as interpreters, fixers and local guides to US and allied soldiers since the start of Afghan War in 2001, when Western forces invaded to wrest control of the country from the Taliban.

Decades after the beginning of what would become America's longest-running conflict, President Joe Biden has vowed to withdraw US troops by 11 September - even as the Taliban appear poised to return to power.

A prolonged exodus

Mr Biden promised that a mass evacuation of interpreters would begin before August, and on Friday, 200 Afghans out of an initial group of 2,500 arrived in the US to complete their visa applications and begin new lives.

As many as 50,000 interpreters have worked with the US military. Since 2008, some 70,000 Afghans - interpreters and their families - have moved to the US under a special immigrant visa awarded for their service. But some 20,000 interpreters and their families are still seeking a way out.

On Monday, the US state department announced it would set up a second refugee programme, meant for Afghans who worked for US-funded projects and US-based media outlets and non-governmental organisations.

But these applicants face a clogged and complex visa process and the threat of a swift Taliban advance as the US winds down its 20-year war.

The danger to interpreters - marked for their work for the Americans - is grave. An estimated 300 interpreters have died since 2009 while seeking a US visa - a process that can take years, even under newer refugee schemes.

The delays have stung Zia.

"These people stood up and fought shoulder and shoulder to support both countries… and we're closing our eyes and leaving them there, leaving them to die," he said.

Brothers in arms

Zia signed up to join the US military as an interpreter in 2002.

At 18 years old, it was his first full-time job.

"We were the eye and the tongue of the military," Zia said

To hear Zia tell it, it was also the realisation of a promise made to his mother six years earlier, when the Taliban swept to power in Afghanistan.

Then a grade school student, Zia saw the sudden end of a carefree childhood, an easy rotation between school, soccer, and games with his seven siblings.

Zia recalled his lively neighbourhood transformed under strict Islamic rule - indiscriminate beatings of men and women, a strange quiet as families hid indoors, his sisters barred from school.

His older brother, then in his twenties, was beaten and thrown in prison after he was overheard speaking the dialect of Panjshir valley, then the centre of anti-Taliban resistance.

The beating left his feet and legs so swollen, he couldn't put on his boots, Zia said. The injuries were so bad he was unable to walk.

Within days, his parents decided they couldn't stay. The family fled from their home in Kabul, moving to Pashawar, Pakistan. "I told my mom, 'When I grow up, I will fight against these people,'" he said, referring to the Taliban.

In Pashawar, he learnt English at school.

His family remained in Pakistan until 2001, when the US began its decades-long invasion.

"When I got back, I saw a stable government was starting," Zia said. "I said ok, now we have a hope."

He settled back into life in Afghanistan, got married and began teaching English at a local school. Within months of his return, a friend told him the Americans were in need of interpreters.

They went the very next day, he said, showing up at the base in Kabul asking about a job.

"They were just hiring people who could speak English. I didn't know military words, they told me 'no problem,'".

He loved the work, he said, despite the months-long tours away from home, and the acute threat of serving on the front lines.

He resisted pleas from his wife and family to retire, saying he was devoted to his "brothers" of the US armed forces, who gave him his nickname, "Booyah".

"We were the eye and the tongue of the military," Zia said.

For Zia, working with the Green Berets, this meant near-constant proximity to violence and death.

In April 2008, he accompanied US forces in the Battle of Shok Valley. Minutes into the six-hour firefight his best friend, another interpreter, was killed. The battle spawned the highest number of Silver Stars - the second-highest decoration for valour - of any battle since Vietnam.

Zia was awarded an unofficial Purple Heart for wounds sustained in battle

While the Purple Heart is only officially awarded to members of the US military, members of the Special Forces team to which he was attached gave him an "unofficial" version of the award in recognition of his wounds.

When he arrived in the US, shrapnel from that day was still in his body, he said.

He applied for US visas that year, under a new visa programme created by Congress in 2008 - the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) - designed specifically for Afghans and Iraqis who worked alongside American troops in both of those conflicts.

Zia's visa took six years to be approved.

A soft-spoken, affable man, he called the process "disgusting".

The delays were inexplicable, he said.

"I don't know why it takes so long, we are already in the United States' database," he said. "I don't know who could explain to the State Department what these guys have done for both countries."

'I can't take anything'

Zia received his approval in an email in the summer of 2014, while on duty in Jalalabad, Nangarhar province.

He felt "strange", he said, daunted by the prospect of leaving Afghanistan behind. "I can't take anything I had built."

The Taliban forced his hand. His family had begun receiving "night letters" - handwritten threats from the militants meant to discourage cooperation with US forces.

Three months after their approval, Zia and his family boarded a commercial airplane for Nashville, Tennessee - weighed down by several duffel bags of clothes and a $6,500 bill for the flight.

When they landed, they found no support or safety net. Zia was startled by the unfamiliar.

"I couldn't find any Afghans over there," he said.

Zia loaded his family into a hired taxi and drove one state over to Mannassas, Virginia, where he had heard lots of Afghans lived. They stayed in a hotel while Zia tried to get his bearings, reaching out to organisations meant to help special immigrant visa holders.

After a few weeks, a volunteer called back, saying they had found his family a place to live and begin their lives.

"She took me to a homeless shelter," Zia said. "I looked around and said 'this is not a place for my children to grow up.'"

They had nowhere to go, and Zia again felt left down by the country that had promised to take care of him. His kids, too young to fully understand, were scared and confused. Each day, they asked their father about the family and friends left behind and when they were going back home.

'This is your house'

Desperate, Zia placed a call to his former captain and told him where he was.

"He was so pissed off," Zia said. Days later, his captain arrived in Virginia and drove Zia and his family back to his home in North Carolina.

"He told me: 'This is your house,'" Zia said. "As long as you want to live here, you can."

"I will never, ever forget that."

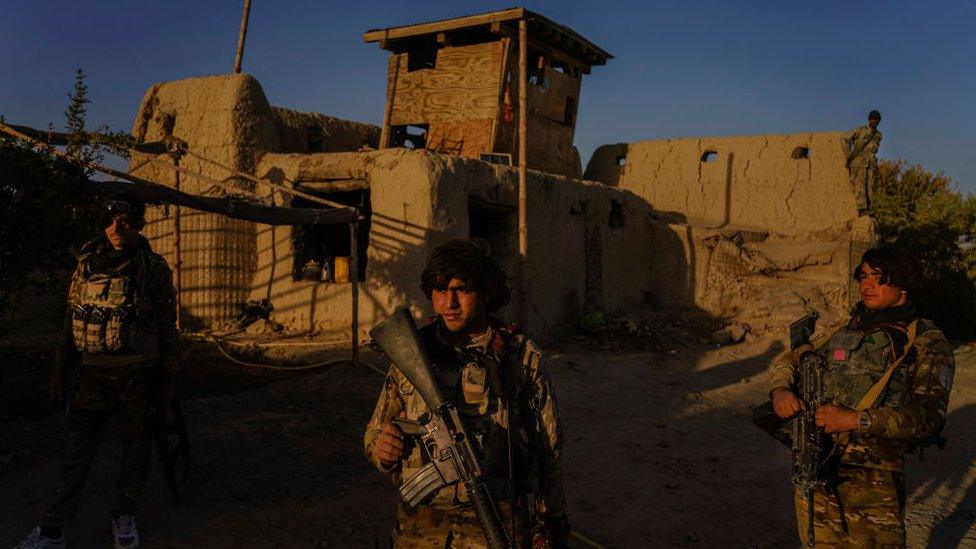

Afghan national forces have struggled against a rapid Taliban advance

Zia was eventually able to move his family to their own apartment in Charlotte, where he worked in construction and later at a convenience store.

North Carolina wasn't like the places he had heard about from his American colleagues - New York City, Washington DC, Las Vegas. But he relished the simple security of their new lives: his kids' safe trips to and from school, his wife's freedom to go out, to work.

His four children quickly became fluent in English, and the former interpreter is teased for his language mistakes. Last year, Zia, his wife and their three oldest children were sworn in as American citizens. His youngest son, now six, was born an American, and speaks with a slight southern accent.

About two years ago, the family of five moved into in a modest, clapboard home in a quiet cul-de-sac. A large American flag hangs from a pole outside.

'Nothing has changed'

But Zia's view from Charlotte is clouded by the people left behind.

In 2019, he launched the Interpreting Freedom Foundation, a charity meant to help interpreters with the SIV process and resettlement in the US. He now fields nightly calls from former interpreters and their family, desperate for a way out.

Most are trapped within a complex bureaucratic process, buckling under a years-long backlog.

Adding further complications - US evacuations are taking place only out of Kabul, meaning Afghans living outside the capital will have to face a potentially fatal journey through Taliban-controlled territory - a rapidly expanding area.

Since the US announced its withdrawal in April, the number of Taliban controlled districts has tripled from 72 to 221, according to the Foundation for the Defense of Democracy, a DC-based nonprofit. The US government has said it's possible that the Afghan government will collapse as soon as next year.

Some of the provinces most at risk of a Taliban takeover, like Kandahar and Helmand, were home to thousands of US troops and their local interpreters, who now face threat of capture or execution.

Interpreters are in "mortal danger", said retired Col Mike Jason. "This is not a mystery. Our interpreters have been assassinated for a decade plus."

Proof of former employment with the US military - the types of documents necessary for a visa application - amount to a "confession" in the eyes of the Taliban, he said.

"We're at a point where I don't know how they can get out," he said.

The State Department has promised to expedite the process where possible, but the flat-footed response has angered veterans and interpreters alike.

"It's not a surprise that we're leaving… this isn't something that was suddenly thrust upon us," said Joe Kassabian, an author and US army veteran of Afghanistan. "We should have planned ahead, and now we're acting like we need to do an emergency evacuation."

For Zia, the US withdrawal reads as abandonment. He has struggled to watch Afghanistan return to the way it was when he first fled as a child.

"The Taliban are still killing innocent people," he said. "Nothing has changed."

And even more so, he has struggled to understand how the Americans have sent their soldiers home, while leaving their allies behind. He loves his adopted country, he said, but thinks its politicians have betrayed him and others who served.

"They're trying to wash their hands of us," he said.

Tens of thousands of Afghan interpreters are still seeking a way out

Chelsea Bailey contributed research

Correction 9 August 2021: An earlier version of this article wrongly reported that Zia Ghafoori was awarded a Purple Heart for wounds sustained in battle. However the Purple Heart is only awarded to United States military personnel and it has since been established that Zia was referring to an unofficial award conferred on him by his unit. We have amended the article to make this clear.

Related topics

- Published9 July 2021

- Published28 February 2021

- Published16 August 2021