Afghanistan pullout: Biden's biggest call yet - will it be his most calamitous?

- Published

If you like neat lines, tidiness and admire symmetry, what's not to like about the decision of Joe Biden to pull American combat troops out of Afghanistan by 11 September 2021 - exactly 20 years on from 9/11?

In modern day America it often feels that all roads lead back to 9/11; the single most defining - and scarring - event since Pearl Harbor: the surprise attack by the Japanese on America's Pacific fleet, which would ultimately bring America into World War Two.

And so it was that 9/11 led to this country's longest military encounter. The attack on the Twin Towers, the plane that flew into the Pentagon, and the one that crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania, were initially the spur for a surge of US nationalism. Young people - in fact people of all ages - were going along to armed forces recruitment offices wanting to sign up. America had come under attack; these patriots wanted to fight to defend the country the "land of the free", and seek revenge on those who would do the US harm.

And don't mistake this for some kind of kneejerk jingoism. It wasn't that. I knew many people - not just Americans - who were of a liberal bent and had been no great fans of all the doings of the US of A but who have a visceral sense this was a moment where you had to pick your team.

Were you on the side of the rule of law, free and fair elections, due process, sexual equality, universal education? Or were you on the side of those who would fly planes into buildings, or would stone people to death, or throw homosexuals off of buildings, or deny girls schooling? If that seems a massive over-simplification, maybe it is - but in the devastating aftermath of 9/11, that is how it seemed to many.

Biden makes a surprise visit to Afghanistan as vice-president in 2011

But by 2016 it was one of the factors that led to Donald Trump's election: the weariness of the "endless wars" as candidate Trump would refer to the quagmires of Afghanistan and Iraq; the wariness of America being able to act as the world's policeman.

Americans understandably wanted to pull up the drawbridge, bring the troops home, leave it to the people in those countries to sort out their own problems, and finally give up on the idea that a US model of liberal democracy was an exportable commodity that could be imposed. The liberal interventionist crusade was over.

Trump, if he had won last November, would have pulled out US troops, probably quicker. Although Joe Biden inherited Trump's promise to withdraw, in policy terms the easiest thing would have been to continue to sign the cheques to pay for American servicemen and women to stay in Afghanistan for another year. And then another. And another after that.

The political pressure was by no means overwhelming. If anything, the reverse. The defence top brass, the foreign policy establishment, America's allies abroad thought anything other than the status quo would be reckless. But one question was gnawing at the new president, and it was the one posed by Hillel the Elder back in biblical times: "If not now, then when?"

Biden - who advised President Barack Obama not to send more troops in 2009 but lost the argument - went with now, in what could be the most consequential single decision of his presidency.

Taliban leaders speak to BBC News about conquer and compromise

When 9/11 happened I was the BBC's Paris correspondent, reporting on Eurotunnel's attempt to force the closure of a Red Cross refugee centre called Sangatte - where many of the world's storm-tossed refugees and migrants congregated before making the final leg of the journey to the UK.

I was driving to Calais when I got a call from a colleague telling me to stop at the nearest service station to watch TV, and see what was unfolding.

We didn't know what would happen next - or where we would end up. One year into the optimism of a new millennium, there was a narrative and it wasn't a happy one - the war on terror, a clash of civilisations, call it what you will. At the time the two stories could not have been more different, but a lot of the bedraggled people we met on the roads around Calais were from Afghanistan fleeing Taliban rule.

It's worth remembering why the US, UK and others went into Afghanistan. The Taliban had - in effect - become a finishing school for Islamist terrorists wanting to wage jihad against the west. Al-Qaeda wannabes were going into the country to train for holy war. The 9/11 terrorists had honed their skills and hatched their plot there. Removing the Taliban and tackling al-Qaeda became critical for global security.

Within a few weeks of 9/11, I was in northern Afghanistan, travelling via Delhi and then Dushanbe in Tajikistan to get there. We were moving with the US and UK-backed Northern Alliance troops as they pushed the Taliban out.

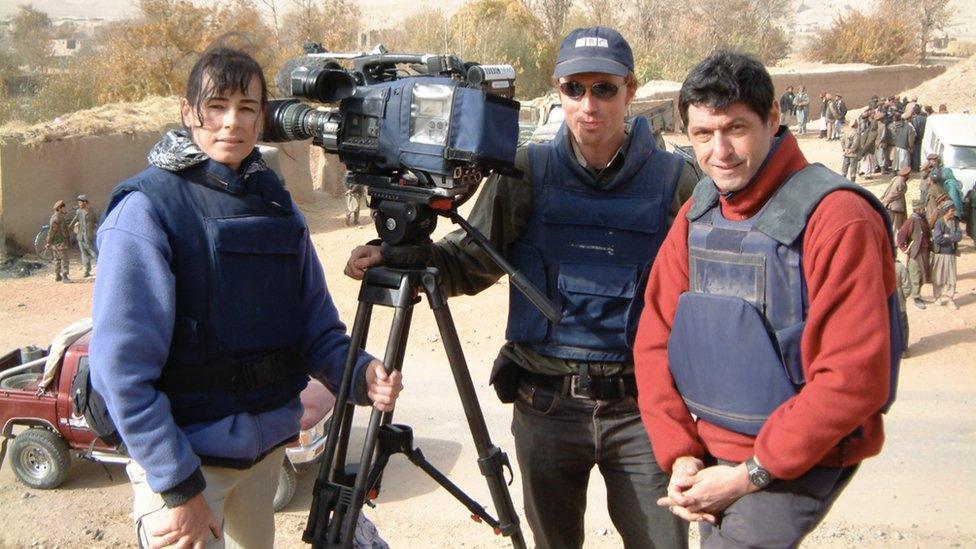

Ousting the Taliban was considered a global priority 20 years ago, writes the author (right)

Our first day was spent travelling from Khoja Bahauddin, then the Northern Alliance HQ along a road where the Taliban had killed a number of journalists in an ambush two days earlier. After one night we ended up in a town called Taleqan. It had fallen the night before we arrived. One of the iconic shots was of a girls-school classroom that had become a weapons dump for Taliban rockets that in their hasty retreat they had left behind.

The stubborn last stronghold was Kunduz - a vital communication corridor sitting between Kabul, Mazar-i-Sharif and then further north to the border with Uzbekistan.

Now both Taleqan and Kunduz have come back under Taliban control, with a third of the country's regional capitals now under their control.

And that raises a super-uncomfortable question for Joe Biden and his "if not now, then when" policy.

Twenty years on and so many lives lost, and so many billions of dollars spent, what was it for? What's been achieved? What do you say to the families of all those servicemen killed by the Taliban now that the US is giving up? What's to stop terror groups from re-establishing their jihad training camps? At the UN Security Council hearing last Friday it was reported that up to 20 different terror groups, involving thousands of foreign fighters were already fighting with Taliban forces.

The regions where Jon travelled are now back under Taliban control

I'm sure as I am writing this more families will be packing up their possessions fearful of what Taliban control will mean, perhaps heading to Calais and then the UK. Will the girls' schools return to become weapons storage facilities again?

The scars of 9/11 are clear everywhere - thousands of servicemen have come back with prosthetic limbs and disturbed minds. Suicide rates have been rising. Families have lost loved ones. On America's streets are men with red plastic beer cups begging for loose change, many of them with signs saying they are veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Afghan war - the basics

US-led forces toppled the Taliban: In 2001 US-led forces overthrew Afghanistan's Taliban rulers after the 9/11 attacks masterminded by al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, who was based there.

Twenty years of occupation and military operations followed: The US and allies oversaw elections and built up Afghan security forces, but the Taliban continued to launch attacks.

Eventually the US made a deal with the Taliban: They would pull out if the militants agreed not to host terrorist groups. But talks between the Taliban and the Afghan government failed. US-led forces withdrew this year and the Taliban have now retaken most of the country.

The desire to stay at home and shut yourself away from a troubling world is completely understandable. There is no surprise that "America First" as a slogan had such resonance. George W Bush was not advocating that back in 2001 - but there were no US troops in Afghanistan or Iraq then. And that didn't keep America safe when early that morning, across those gin-clear blue skies passenger aeroplanes were hijacked and became al-Qaeda-guided missiles, flying into their targets killing thousands of people doing nothing more provocative than going about their daily lives.

There's also a difference between enforcing your will as the world's policeman, and being a peacekeeper. Thousands of American troops are still stationed in South Korea - even though the Korean war was 70 years ago. The calculation of successive US presidents has been that a tense peace is better than a hot war or a destabilised region.

Joe Biden was hoping his decision would result in headlines like "Afghan War Ends" or "America's longest war is over". But 20 years on, and the Taliban now re-establishing control with all that could flow from that, might historians in future judge that the 20th anniversary marked the start of the second Afghan war?