To Trump voters, chaos in Afghanistan 'another betrayal' by Biden

- Published

Charles Johnson, a military veteran and pastor, has shed tears over the troop withdrawal in Afghanistan

From the outside, it might seem odd that the voters of Sandy Hook, Kentucky, are so deeply distraught by the withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan that some speak of the events with tears.

The vagaries of America's foreign entanglements do not usually much figure into the lives of those residing in this tiny hamlet, the seat of Elliott County and its only real town.

Yet as he stood outside his church on a clear Sunday morning, Charles Johnson's voice broke as he described how he saw the US pull-out ordered by President Joe Biden.

It was "an absolute disgrace" that American troops left "in the middle of the night", abandoning Afghan allies who had "sacrificed their lives, and their reputations, and the safety of their families," the preacher said.

"There was no reason for them to die," he said. "They didn't have to die."

Last month's chaotic and deadly end to America's longest running war has spurred widespread criticism of the Biden administration and a drop in public support for the president.

Among allies, it has undermined Mr Biden's message of competence, and in Washington, members of Congress from both parties are demanding answers.

In places like Elliott County, deep in the Appalachian foothills, it is being seen as vindication for voters who rejected the Democrat and had backed Republican Donald Trump.

To some of them it is the confirmation that Mr Biden and his party cannot be trusted to improve people's lives - theirs or anyone else's.

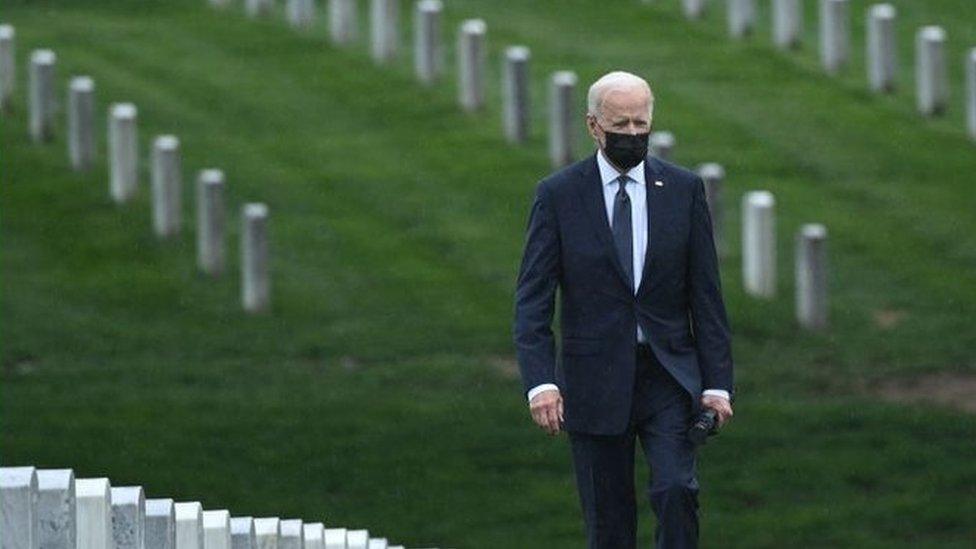

US President Joe Biden walks past the headstones of fallen troops of the Afghan war at Arlington National Cemetery

Sandy Hook is both a surprising and unsurprising place to be rife with such sentiment.

Not long ago, the county was the staunchest Democratic stronghold in the US - until the arrival of Mr Trump in 2016, it had voted "blue" in every presidential election since it was incorporated in 1869, the longest streak in the country.

Support for Democratic politics had been so strong for so long in Elliott County for two reasons. Early on, it was the party of the Old South, still hostile to the values of the North against which a civil war had been fought.

By the 1930s, it was because of the embrace of the New Deal, a vast government programme to create social safety nets and jobs amid the Great Depression.

Jobs, the economy and social policy have always been the things voters cared most about.

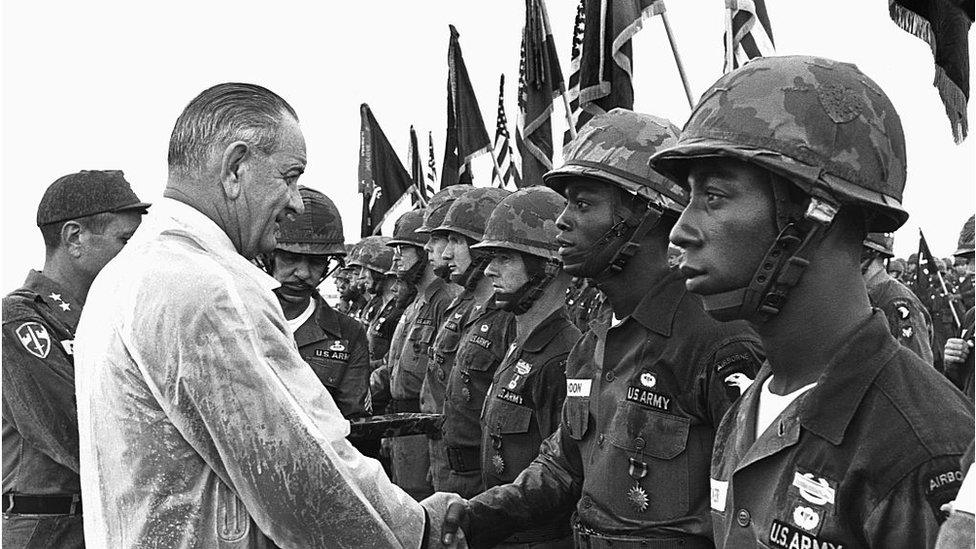

The 1960s Vietnam war did not shatter their faith in Lyndon Baines Johnson, and Jimmy Carter's troubles abroad barely registered here in 1980, when he lost Kentucky but won three-quarters of the vote in Elliott.

The rural hills of Eastern Kentucky have always been a hard-scrabble place

But along with much of the rural American south, the county turned away in the last two elections with the feeling that the party had abandoned them.

Voters saw themselves scolded as "a bunch of yokels addicted to opioids and Mountain Dew, and they don't like that portrayal" said Michael Berheide, a political scientist at Berea College, Kentucky. "And they see Biden as continuing that."

Mr Trump won the county last year by over 50 points, the largest margin anywhere in the US.

President Lyndon B Johnson shakes hands with troops stationed in Kentucky

Few were paying attention when Mr Trump struck a deal with the Taliban to leave Afghanistan.

It did not seem an urgent issue at election time, said Earl Kinner, 82. "You know, nobody was thinking about it," he said, though most eastern Kentuckians, like the majority of the country, "didn't see any sense in being over there".

But the withdrawal from Afghanistan has become a prime example of how mistrust in Mr Biden is shaping perceptions about his policies, whatever they might be.

"Any time that's there's something happening overseas, there's the back story of what's happening here at home that shapes how [voters are] feeling about that," said Melanie Goan, a history professor at University of Kentucky in Lexington.

"They see Biden as the enemy. He stands for positions that they don't accept. You have all these reasons for them to pin the blame on Biden."

To people in Sandy Hook, "Trump comes across as a leader. This fellow, Biden, he comes across as a weak sister," Mr Kinner said.

Carl Simmons, at First Baptist in Sandy Hook, calls Biden’s Afghanistan policy “a disgrace”

Nicole McComas, 33, said: "The leader of the military is the commander in chief. So, whether he likes it or not, it's all on him. There's nobody else he can blame for it. There's not one part of it that I could try to redeem him on".

Many were convinced that Mr Trump would not have bungled the exit as Mr Biden did. Mr Trump would not have left military equipment there, said one. He would not have been seemingly indifferent to the suffering of Afghans, suggested another.

Mr Biden's top diplomat defended the withdrawal during testimony to Congress, claiming that the president had "inherited a deadline, not a plan" from his predecessor. The administration argues the withdrawal would have been chaotic and dangerous whenever it happened.

The irony for Mr Biden is that as he now turns to a domestic agenda that aims to address the grievances of places like Sandy Hook - including a $3.5bn infrastructure plan to bring better connection to rural America, expanding social services and public health and pro-union policies popular with blue-collar workers - he may well find his efforts spurned.

"I don't think that people are going to forgive this bit here, this Afghanistan thing. I don't think people are going to forget," Mr Kinner said. "To people here, he just turned and ran."

Democrats "turned their backs on Appalachia," said Carl Simmons, 60, a coal company purchasing agent - and now, it seemed to him, they had turned their backs in Afghanistan, too.

"We've built in those people some hope that - 'Maybe I can have a better life.' But we dashed that hope," he said.

Related topics

- Published1 September 2021

- Published22 September 2020

- Published15 July 2016