Wayne Jenkins from behind bars: 'I sold drugs as a dirty cop'

- Published

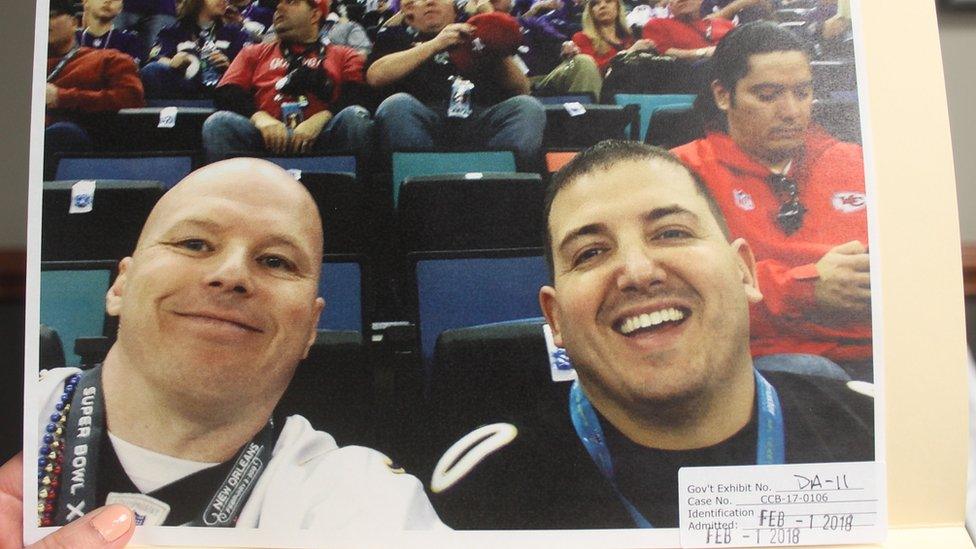

Police who went rogue - Wayne Jenkins and Momodu Gondo

For the past four years, Jessica Lussenhop has been reporting on the rise and fall of a corrupt squad of Baltimore police officers. Just as she was completing her podcast series on the story, she got a very unexpected call from prison.

I'm standing in my pandemic "radio studio" - aka the closet in my apartment - surrounded by hangers holding button-up shirts and dresses. I'm staring at my cell phone in the dark. It's propped up on top of a suitcase sitting on top of a plastic tub, and I'm holding my recorder and microphone at the ready.

When the phone rings, I put the call on speaker and hear a robotic, pre-recorded female voice: "You have a prepaid call. You will not be charged for this call. This call is from…"

A human voice breaks in: "Wayne Jenkins."

"...an inmate in a federal prison," the robot finishes.

Former Baltimore Police Department Sergeant Wayne Jenkins, currently inmate number 62928-037 at a federal prison in Kentucky, is on the line. Until this point, I'd only heard Jenkins on secretly taped FBI recordings, wiretapped phone calls, body camera footage and at the hearing in June 2018 when a federal judge sentenced him to 25 years in prison. It was surreal hearing his voice, talking to me.

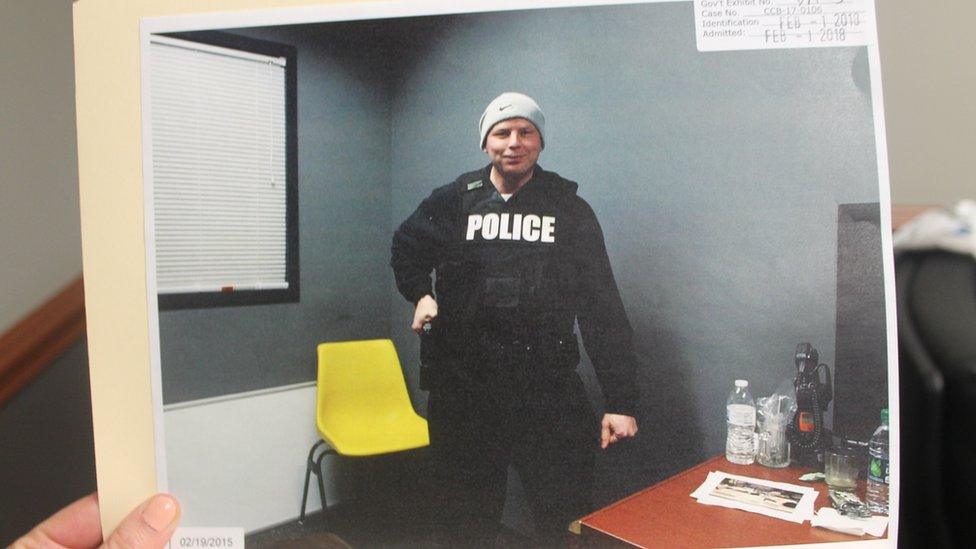

Jenkins, centre, before he took command of the Gun Trace Task Force

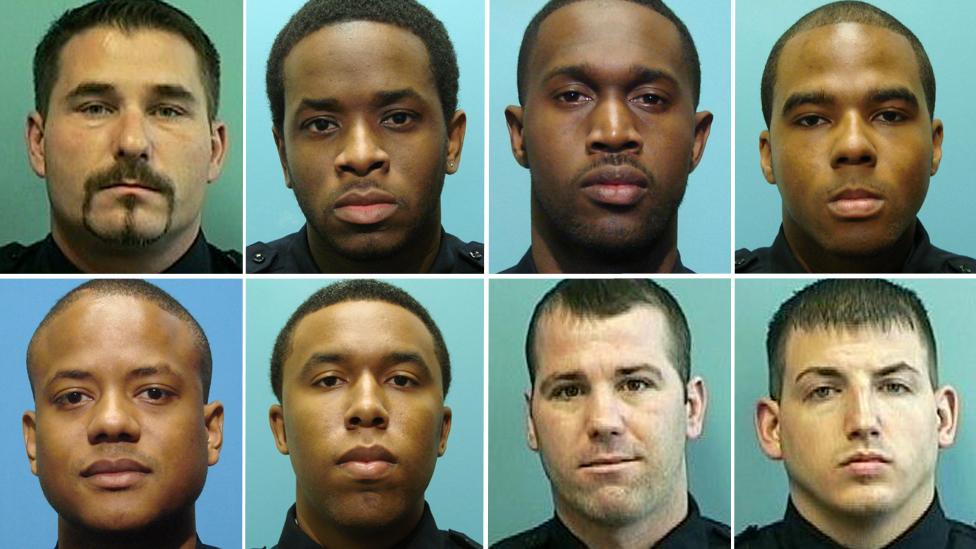

I've been reporting on Jenkins, and the elite Gun Trace Task Force squad he once led, for nearly four years. He and six members of that unit now sit in federal prison for crimes including conspiracy, racketeering and robbery, all committed under the guise of legitimate police work.

They stole drugs and cash, sold seized narcotics and guns back on the street, planted evidence on people, even committed home invasions.

Find out more

In 2018, Jessica wrote a piece which detailed the explosive trial at a Baltimore federal courthouse that revealed the unit's crimes

She then turned that story into a new seven-part podcast series called Bad Cops which you can listen to in its entirety below

Over the years, I wrote to all of these former officers in prison several times, asking them to help me understand their breathtaking crimes. My hope - maybe a naive one - was that hearing one of these men speak candidly about how he crossed over to the dark side would help the public better understand the casual, day-to-day corruption that can happen in policing. I hoped it could spur a more honest discussion about what it's going to take to reform or even redefine what it means to be a cop in the US.

Of all seven men, the last person I thought would ever agree to an interview was Jenkins, the fallen "golden boy" of the Baltimore Police Department. As the leader of the unit, he received the longest prison sentence and the federal authorities who prosecuted the squad viewed him as its most culpable member. In the years since his arrest, he'd never given a public interview.

And yet, here we are, me in my closet "studio" and him at the front of a line of 20 to 30 other inmates, all waiting for their turn on the prison phone. I have no idea what he wants to say, or why after four years, he's breaking his silence.

"Everything I tell you, I will take a polygraph," Jenkins says near the beginning of that first phone call. "I'm in prison for 25 years, there's no reason to lie."

On 1 March, 2017, Sergeant Wayne Jenkins and six of his subordinate officers from the Gun Trace Task Force walked into the Baltimore Police Department's Internal Affairs building, believing they were there to clear up a minor complaint about a damaged vehicle.

Prior to this, they'd been lauded as some of the best gun cops in the city - seizing dozens of illegal firearms every month, and demonstrating a "a work ethic that is beyond reproach", in the words of one supervisor. Jenkins was a rising star in the department, because of his ability to regularly bring in huge seizures of drugs and guns.

But when the officers exited the elevators on the building's second floor, they were met by an FBI SWAT team. All seven members were soon in handcuffs.

It turned out that federal agents had the unit under surveillance for months. Using wiretaps and hidden recording devices, they had accumulated a wealth of evidence showing the officers were robbing citizens, filing for hundreds of hours of overtime they never worked, stealing drugs and even selling illegal firearms back on the streets.

Five of the former officers, including Jenkins, pleaded guilty. But two pronounced their innocence and went to trial, which I covered for the BBC. It was there that the full extent of the officers' misconduct became public.

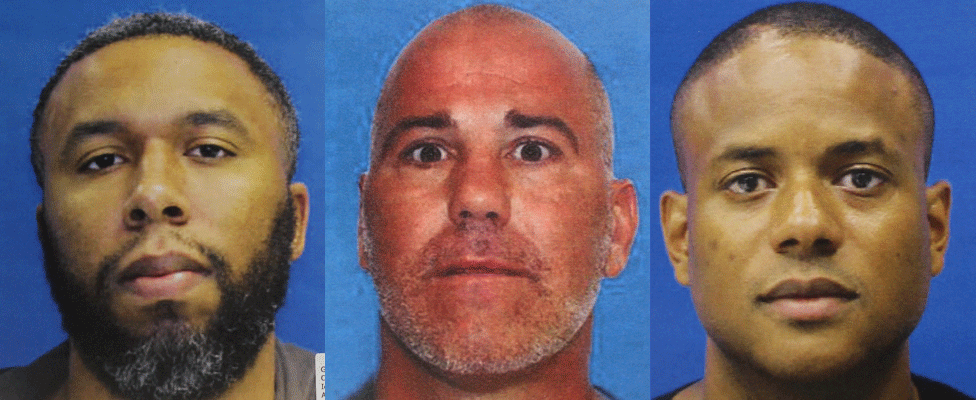

Clockwise from top left: Evodio Hendrix, Daniel Hersl, Jemell Rayam, Maurice Ward, Marcus Taylor, Momodu Gondo

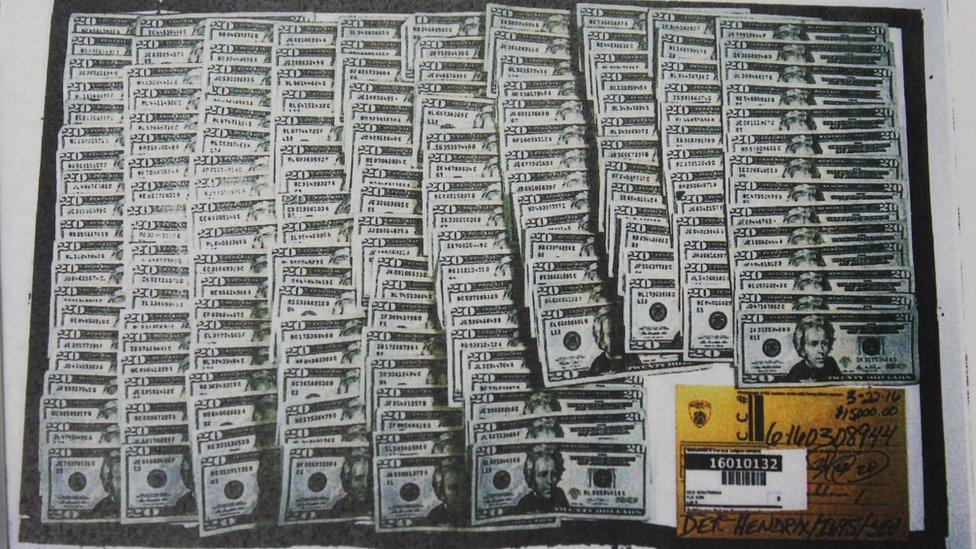

In January 2018, a long list of victims took the stand - many of whom had ties to the drug trade - and told harrowing stories of how they were robbed by the officers during car stops and searches of their homes. Some tried to complain, but were ignored. Shawn Whiting, a man whose house was robbed of $16,000 and a kilo-and-a-half of heroin, testified that he knew that as a drug dealer, his word counted for much less than the officers'.

"I ain't have a trial because the simple fact is I knew [the court] would believe them over top of me," he told the jury.

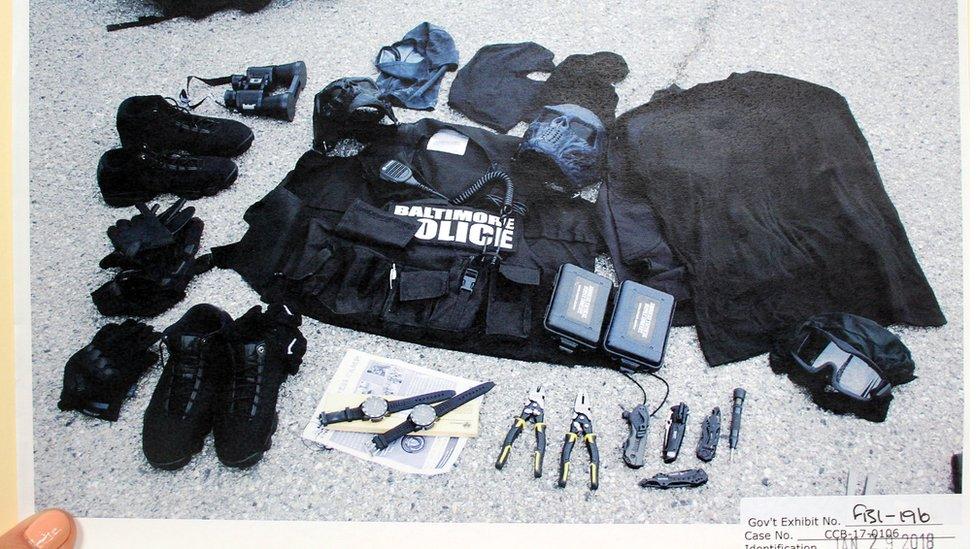

Several of the former officers also took the stand - now wearing prison jumpsuits instead of uniforms - and detailed the tactics encouraged by their leader, Jenkins. They testified he told them to carry BB guns to plant if they ever injured or killed an unarmed person, that he often took large quantities of drugs off of suspects without submitting them to the police evidence room. Two officers said he spoke openly about doing home invasions on high-level drug dealers that he called "monsters", because of the amount of drugs and cash he hoped they'd have stashed in their houses.

One of the most surprising witnesses was a man named Donald Stepp, a bail bondsman, who revealed that he'd been selling drugs Jenkins brought him from work. He said together, they'd sold about $1m worth of narcotics.

"It was a front for a criminal enterprise," Stepp said of the Gun Trace Task Force. "It was obvious to me, when I'm taking millions of dollars worth of drugs from the Baltimore Police Department and selling them, that… this is not a normal police department."

Stepp testified that the arrangement was so lucrative, he stuck with it for years before getting arrested himself in December 2017.

"I'm here because of greed," he said. "It's that simple."

Jenkins did not testify at the trial, but in a way, he was the star of the entire proceeding.

After three weeks of astonishing testimony, the jury found the two remaining officers guilty. All seven now sit in federal prisons scattered across the country. The longest sentence was handed down to Jenkins: 25 years. He's due to be released in 2038.

After he was sent to federal lock-up, I wrote Jenkins a letter once a year - along with many other journalists, book authors, producers and documentary filmmakers - requesting an interview. I never heard back, and he didn't seem to be responding to anyone else, either.

I assumed he never would.

This past summer, as I was wrapping up work on "Bad Cops", a strange email appeared in my inbox. The message read: "Greetings. I am Agent and Representative as to Mr Jenkins. Contact me."

A strange back and forth with a man who used to be Jenkins' cell mate ultimately ended up with me in my closet waiting for that call.

In the gloom I see the number of the bureau of prisons light up my cell phone screen.

"Hi, ma'am," Jenkins says when I pick up. "This is Wayne."

In federal prison, inmates are only allowed to talk on the phone for 15 minutes before the line is automatically cut. I have so many questions to ask, and I'm not sure if this will be my one and only opportunity to speak to him.

"Especially because we're short on time, is there anything that you kind of want to just say right off the bat?" I ask.

"Right off the bat, we wasn't living lavishly. I lived modest, we wasn't enriching ourselves," he answers. "I never had [theft complaints] because I never took money off individuals. I did give drugs to Donny for the last couple of years I was police, but I didn't take people's money because then they would know you were dirty. So I kind of had a mental, like maybe a messed up moral code."

Right away I learn that Jenkins is an incredibly fast talker. I have to try to untangle his answers as he moves from subject to subject, sometimes so fast I can't keep up. The first 15 minutes are over in a flash. The line goes dead, and I feel like I've barely gotten anywhere. But then, about an hour later, the phone rings again. Jenkins tells me he traded some sausages with other inmates in the line, bartering his way to the front.

Over the course of four phone calls (courtesy of some traded bags of crisps), Jenkins paints a picture of the Baltimore Police Department as a place where indoctrination into corruption starts almost immediately. He tells me that the first time he ever stole money, he was just a rookie. It took place as Jenkins and other officers were searching an apartment. In the bedroom, Jenkins says he and a veteran supervisor found a suitcase filled with tens of thousands of dollars in cash. Jenkins says that the veteran goaded him into taking money.

"He's like, 'I'm not telling you to do anything, I'm just saying it sure would be nice if we had $10,000 apiece to go up to Atlantic City,'" Jenkins recalls. "And I remember taking the $10,000."

A lot of what he told me was much more systematic. He claims that he was told early on to lie on police reports and warrant applications in order to make their arrests sound like they were done with proper probable cause, meaning a legal reason to stop someone. In reality, he says, they were making arrests by any means necessary.

"This is a saying we state: 'Don't let probable cause stand in the way of a good arrest,'" Jenkins says. "If you've got to lie about what you've seen or what you heard or what you witnessed, as long as he's dirty, he's got the drugs and he's got the guns and he did the crime - just get him."

He told me that frequently, when he or his fellow officers didn't feel like submitting the drugs they seized or doing arrest paperwork, they'd simply confiscate people's drug stashes and let them go. Later on, he claims, they'd throw the drugs out the window or down a sewer grate.

"Pills of heroin, bags of marijuana," he says. "Seen it done, honest to god, 500 times."

Jenkins names two specific locations where he says the drugs get tossed: a train bridge near the Eastern District police station, and a wooded highway off-ramp on the way to the Northern District police station. Weeks later, I search these locations myself to see if I can find anything.

On the off-ramp, I find four empty dime bags scattered along a section of sidewalk with no foot traffic. But nothing more.

Jenkins also tells me that any time an officer's misconduct gets picked up by Internal Affairs or by an outside law enforcement agency, it was routine for the involved officers to meet up, to tailor their stories to avoid punishment.

"Immediately, we get together and you go over your story. 'You say this, you say that, right?' You're taught that - the second someone gets in trouble we meet up, and we talk face to face," he says.

As Jenkins is telling me this, he is naming names. He names the veteran he says coached him into stealing for the first time. He also names two former supervisors who he says he complained to about his former subordinate officers, Momodu Gondo and Jemell Rayam, saying they had bad reputations for stealing money. He says he was told that because these officers were so successful at seizing guns, there was nothing to be done.

The BBC is not naming these three former supervisors, since none of them has been charged with a crime in connection with this case. But I did call them, and the Baltimore Police Department, to see if anyone would respond to this laundry list of allegations.

One former supervisor never responded. The second declined to comment. The spouse of the third left a message telling me I could take what Jenkins told me and "stuff it".

I never heard back from the Baltimore Police Department.

The conversation with Jenkins gets more complicated when we turn specifically to the crimes of the Gun Trace Task Force.

Jenkins signed a plea agreement in 2017 that detailed seven robberies that he participated in along with other members of the unit, as well as his drug dealing partnership with Donald Stepp, the former bail bondsman and cocaine dealer who testified at trial. Jenkins admitted that he stole drugs from work and delivered them to Stepp, who would turn around and sell them. The pair also stole valuables, like high-end wrist watches, in break-ins.

But Jenkins wanted to argue the details in his plea agreement, saying many of them weren't true. A plea agreement is a document that lists specific criminal acts that the defendant is agreeing to plead guilty to. Jenkins had to affirm under oath in front of a federal judge that what the document said was true. It was difficult for me to understand and parse all of Jenkins' denials, now.

For example, I asked him about the robbery of a man who lived in a large mansion in the suburbs of Baltimore - a robbery he pled guilty to in his plea agreement.

"There was cameras everywhere, so I would never have took a dollar," he tells me. "Later on that evening, Gondo did give me money, that means hours later, I'm talking hours later, he gave me money."

"So you did take money, ultimately?" I ask, slightly confused.

"I did, yes. Yes, I did," he says. He also acknowledged stealing the man's $4,000 (£2,956) watch, which he gave to Stepp to sell.

In another man's house, the GTTF broke into a safe and stole hundreds of thousands of dollars. In our conversation, Jenkins says that that's not true - members of the squad did steal money that day, but from somewhere else in the house. It feels a little bit like splitting hairs.

Equipment that two of the GTTF officers testified was going to be used for home invasions

When I point out he already pleaded guilty to all these incidents, Jenkins tells me he only signed the agreement because he feared that if he went forward to trial, he could've wound up behind bars for life. He says he couldn't risk it as a father with a young family.

"Life in prison with three small children. Now I deserve 10 to 15 years... I sold drugs as a dirty cop," he says. "I got 25 years. I got gangster charges, racketeering charges, things they usually give the mob, who were burying bodies in cement."

I also point out to him that it's a fairly common practice for prosecutors to level charges that are so serious that the defendant feels they have no choice but to plead guilty. In fact, it's highly likely - if not certain - that many of the people Jenkins' put in prison himself had those tactics used on them by prosecutors.

"Obviously I'm in here now, so I see both sides. If I could take everything back in my life, I would have been a prosecutor," he says. "I'd rather be a prosecutor so I don't overkill people. You never know until you get on this side, including me, what you do to families."

One of the most shocking incidents from the plea agreement is an event that Jenkins now unequivocally denies. In the spring of 2015, the city of Baltimore was rocked by civil unrest after the in-custody death of 25-year-old Freddie Gray. At one point, dozens of pharmacies were looted and millions of dollars worth of medication went missing. In Jenkins' plea, it says that "in April 2015 following the riots after the death of Freddie Gray, Jenkins brought DS prescription medicines that he had stolen from someone looting a pharmacy so that DS could sell the medications".

"DS" stands for Donald Stepp.

"I never took a thing. I was a hero," Jenkins says of his activity during the unrest. "I never took nothing from a looter, so help me god. Donny made every piece of that up."

Donald Stepp was released from federal prison back in January of this year. He served 20 months of a five year sentence in connection with the Gun Trace Task Force case, before being granted a compassionate release.

Stepp was on home confinement for six months with an ankle monitor until this summer. Today, he's a free man, living without restrictions with his spouse and young daughter in the eastern part of Baltimore County. He's doing, as he likes to say, "rather swell".

But when I tell him that I've interviewed Wayne Jenkins, his one-time drug partner, Stepp is displeased, to put it mildly. There is no love lost between these two former friends.

"He's never been a true friend," Stepp says. "I have no respect for him."

Stepp and Jenkins' history runs deep. They'd known one another's families as children. As adults, they ran into each other again at an underground card game frequented by Baltimore Police officers. It was during these games that Stepp heard Jenkins boasting about the large drug stashes he often came across during his work as a plainclothes police officer.

At the time, Stepp was running his own bail bond company, Double D Bail Bonds. But he says he was also struggling with a gambling addiction and dealing large amounts of cocaine. That made it very tempting when, sometime around 2011, Jenkins approached Stepp and suggested they go into business together. Jenkins would stop bringing those big drug seizures to the evidence room, and instead give them to Stepp to sell.

"I felt comfortable with it because all the police officers that I met, which were many during the card games, in my opinion, they owned the city," Stepp would later tell the jury at the GTTF trial. "I thought it was a winner."

Stepp says Jenkins started bringing over shipments of drugs on an almost daily basis, putting them in a locked shed behind Stepp's house. The drop-offs included marijuana, cocaine and MDMA, all of which Stepp did his best to sell.

Jenkins started calling Stepp to the scenes of arrests, encouraging Stepp to try to get inside drug dealer's hideouts to steal whatever cash or narcotics he could find. They tracked other dealers and broke into their houses when no one was home. This partnership lasted for five years.

In December 2017, eight months after Jenkins was arrested, the FBI and Baltimore County officers broke down Stepp's door and arrested him in his kitchen. It didn't take long before Stepp began to suspect that Jenkins ratted him out.

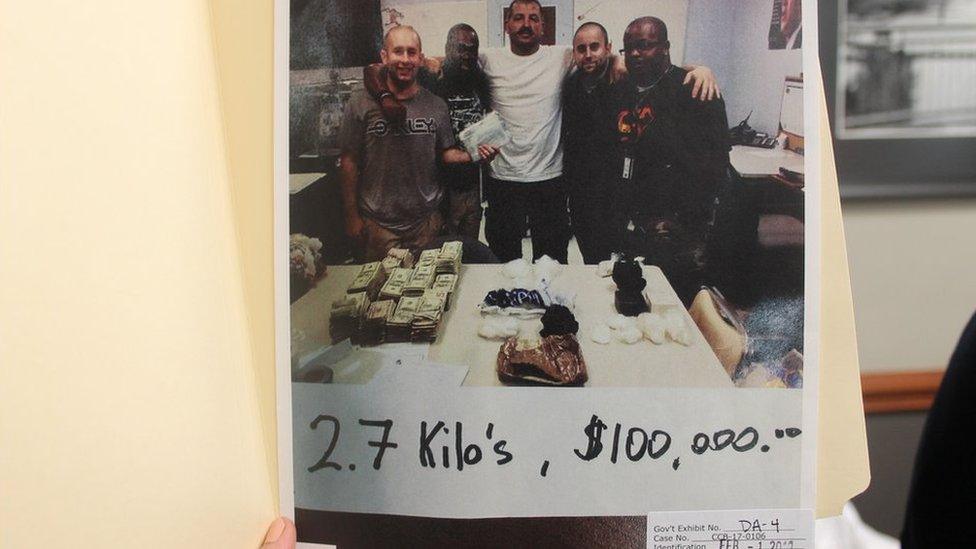

But Stepp had an ace up his sleeve - for months, he'd been documenting their crimes on his cell phone. He took pictures of himself and Jenkins together inside the police department, where Stepp would sometimes pick up drugs. When Jenkins called him to a house the GTTF was investigating, Stepp took pictures of the officers going in and out. Later, Jenkins came out carrying two kilos of cocaine he tossed in Stepp's vehicle.

Stepp turned everything over to the US prosecutors. In part due to his cooperation in the case, he received a much shorter sentence than the officers of the GTTF.

"He drew first blood," Stepp says of Jenkins. "Now we're going to burn it down. And that's what I did."

Not long after Stepp flipped on his former friend, Jenkins pled guilty.

In my conversation with Jenkins, he spent a lot of time disputing Stepp's account of their partnership. He claims that it was Stepp's idea to start selling drugs together, not the other way around. He says Stepp pressured him into it. He also says that he only made roughly $75,000 off of the narcotic sales, as opposed to the figure put on it by Stepp. He calls Stepp "the biggest exaggerator I've ever met in my life".

When I tell this to Stepp, he's angry. He states flatly that Jenkins is lying to me. He points to the plea agreement, in which Jenkins agreed that his cut of their drug sales came to roughly $250,000. He reminds me that the US Attorney's office found him more credible than Jenkins.

"He's a pathological liar," Stepp says. "I fear nothing he knows or anything. Because believe me, I'll stand my ground in a second."

Donald Stepp inside Baltimore Police headquarters, in a photo taken by Wayne Jenkins

Stepp's moving on with his life - in a sense. In March, HBO announced a new miniseries by David Simon, the creator of the classic Baltimore true crime series, 'The Wire'. Simon's new project will tell a fictionalised version of the Gun Trace Task Force saga, and began filming on the streets of Baltimore over the summer. Wayne Jenkins will be played by Jon Bernthal, the same actor who portrayed "The Punisher".

HBO asked Stepp to be a consultant on the project, which he enthusiastically agreed to do. His fee will be donated to the victims of the Gun Trace Task Force. Meanwhile, his Twitter account is full of pictures of him on set, hamming it up with Bernthal and some of the other actors.

He's opening a consulting service called Stepp Right Consultants, to give guidance and insight to men and women who are about to enter the federal penal system. He's also at work on a memoir, which he says will reveal the contents of videos and photos he took of Jenkins that were never released publicly. He's even got a clothing line coming out around his defunct bail bond business, Double D Bail Bonds.

While he may not be ready to let go of his animus towards Jenkins, Stepp's strange journey seems - at least for now - to be heading towards a happy ending.

"It's a surreal story. But it's the big man upstairs," he says. "I'm grateful, very grateful."

I asked Wayne Jenkins several times why he wanted to do the interview with me. He gave me a few reasons.

One was that he felt he'd been railroaded into his plea agreement by the US prosecutors (the Maryland US Attorney's Office declined to comment). Another was to talk about how futile life inside the penal system is.

"I swear, I wish I would have known before I ever put anyone in here… I wish I would have known the other side," he says at one point. "It's nothing I've ever imagined. It's no wonder people come out meaner than when they come in."

And of course, Jenkins is also hoping for a sentenced reduction of some kind.

But I think he also spoke to me because he doesn't like the image of himself that's been in the media - as a sociopath, as someone almost inhumanly evil.

Back before our interview, Jenkins' representative wanted me to speak to some of his old high school friends. They wanted to tell me that Jenkins was a dedicated father, a good football coach. A loyal friend. They told me they were disturbed that he was being portrayed as a "monster".

It wasn't the first time I've heard that word to describe Jenkins. While no one should forget for an instant that Jenkins and his officers caused untold harm to Baltimore citizens, I don't find it helpful to try to write him off as a "monster". The idea that the Gun Trace Task Force went rogue simply because their sergeant was uniquely evil ignores all the systemic ways in which he was encouraged to operate the way he did, and the larger policing culture that supported him (it should also be noted that several of the squad's members started stealing money long before they joined the GTTF).

To single him out as a flawed individual in an otherwise perfectly functioning system is a way to avoid change in the police department, to shirk the responsibility of actually preventing this from happening again. It's going to take an almost unimaginable kind of effort to dig out the roots of corruption in the department, and it's much easier to just lock up the cops who get caught, and carry on with business as usual.

Yet another of Jenkins' friends said something I wasn't expecting. He acknowledged that he could tell something was off with Jenkins around the time of the GTTF crime spree.

"We're not stupid. We knew he wasn't the straight-and-narrow cop that all cops are supposed to be," he said. "He always had large sums of money in his pocket. Used to tell me he won it playing poker."

I ask this friend why he didn't say anything to anyone. He says something that I've never heard anyone admit out loud.

"We said, 'You know, he's robbin' the pieces of shit of Baltimore that are the reason that me and my kids can't walk down the street and feel safe," he says.

This kind of mindset assumes that the victims of the Gun Trace Task Force - many of them black and poor - deserved what happened to them. It's a depressing fact that this is a viewpoint likely shared by many in Baltimore, and is a part of the reason why the GTTF got away with what they did for so long.

The GTTF did not hold a monopoly on harm, of course. Baltimore can be a complicated and dangerous place, and the men and women the officers targeted and abused may have caused harm and abuse themselves. Some of the most upsetting conversations I had were with people who felt victimised twice -- by both the officers and by the criminals. The important difference, however, is that the drug dealers never swore an oath to serve and protect. They weren't being paid by the taxpayers to keep the city safe, and weren't operating with all the power and protections that police have.

I couldn't help thinking about the many victims of the squad that I'd met over the three years I've been working on this story. My thoughts return to Kenneth Bumgardner, a hard-working father who was chased by the squad when they suspected him of having marijuana. He woke up on a frigid city street with his jaw shattered, and couldn't eat solid food for months.

"I'm finally trying to get my life back on track," he told me. "It's still hard though, because I get a lot of pain in my mouth at night…. I'm losing a lot of teeth, you know, they used to be nice and pretty."

I think about Shawn Whiting, a former heroin dealer who went to prison for years after the officers robbed him. He couldn't get anyone to believe him at the time, and to this day, he fears law enforcement.

Shawn Whiting, centre, at a press conference held by victims of the GTTF

"You have nightmares about police officers harassing you, beating you up, just locking you up, it's just a nightmare that I have and it basically hasn't gone away yet," he said. "I just go through this on a daily basis, scared of police, wondering when they gonna stop you, trying to plant drugs on you or something like that. Or harm you or even kill you."

Victims like Bumgardner and Whiting had the courage to speak out. There's no telling how many other people were affected, but were too afraid to come forward. Someone once told me that it will take a generation for the direct impact of the Gun Trace Task Force to start to fade, and it will be impossible to measure how the victims' trauma will play out in the lives of their children, families and friends. The fallout of the squad's crimes is still rippling through the city and undoubtedly made Baltimore a less safe place for everyone who lives there.

I continued working on this story for as long as I did out of some hope that the more the public learned about the corruption in the police department, the better chance there might be of some kind of true, systemic reform.

But Whiting is not so optimistic. Four years after the Gun Trace Task Force officers were arrested, he says he sees no difference on the streets of Baltimore.

"How police act towards people ain't changed," he told me recently. "I see some police officers harassing people, doing the same little tactics that the Gun Trace Task Force was doing."

I asked him if he thinks that another scandal is inevitable.

"Absolutely. It's going to happen again," he said. "It ain't over. This just begun."

.

Related topics

- Published7 June 2018

- Published13 February 2018

- Published8 August 2017