The Kansas case that could change how rape is charged

- Published

Madison Smith and her mother, Mandy

Sex crimes are notoriously difficult to prosecute - but one woman in Kansas is using a rarely used 19th Century law to ask her fellow citizens to help bring charges against the man she says raped her.

In 2018, Madison Smith alleged that a classmate attacked her when she was a university student at Bethany College in Kansas. She reported the case as a rape.

The county prosecutor refused to press rape charges, however, saying Ms Smith had merely experienced an "immature" sexual encounter. Her attacker was convicted of assault.

The county attorney's decision prompted Ms Smith, now 23, to use a state law dating back to 1887 to instead call up a "citizen's grand jury". It convened for the first time on Wednesday in what is thought to be the first case of its kind in the US.

A grand jury is usually set up by the officials investigating the case, and determines if there is enough evidence to pursue a prosecution.

This jury, which will meet in secret, will not decide if the accused is guilty or innocent, only if charges should be brought.

WARNING: This story includes graphic descriptions of an assault

In an interview with the BBC, Ms Smith said that she hoped the result would empower others who say they are the victims of sex crimes, and want to press charges. "There are victims' rights," she said.

Most women do not report these kinds of crimes, and when they are reported, they are often not prosecuted. Fewer than 20% of rapes that are reported lead to an arrest, according to research conducted at the University of Massachusetts in Lowell.

"We got to change the culture [around consent]," Ms Smith's mother, Mandy, added.

However, Ms Smith's accused former classmate, Jared Stolzenburg, now also 23, has denied that he raped her. He was charged with battery, to which he pleaded guilty.

He told the BBC that he regretted their encounter - which he admitted had been rough and that he mistakenly believed to be acceptable. But, he insisted, it was consensual.

The outcome of the grand jury in McPherson County, Kansas, will have far-reaching consequences for the accuser and the accused, and perhaps the rest of the country.

Experts say Ms Smith's actions could set a precedent for others to convene a grand jury in cases involving sex crimes.

But those who are accused of a sex crime and who have not been charged may find themselves, as Stolzenburg does, in legal purgatory, waiting to see if they may still face charges.

An encounter that became an attack

Ms Smith was in her first year at Bethany College, a small, Lutheran school a couple blocks from her house, when she used to hang out with Stolzenburg and play board games.

Then one night, in February 2018, she ended up in his dorm room. They kissed, and began to have sex, she told the BBC. Suddenly, he slapped her, she said, then he grabbed her by the throat, and, she alleged, began to rape her.

"I was trying to pull his hands off my neck, and I looked him in the eye, and there was a look I'd never seen before," she said. "This wasn't the person who I thought was my friend. This was a dangerous person."

Ms Smith claims Stolzenburg tried to kill her.

She was so afraid, she said, that she thought it was better to stop fighting. "You just lay there and let what happens, happen," she said. "I was only doing what I had to do to survive."

Describing the events of that night, her voice was steady, almost matter-of-fact, as if she were telling of events that had happened to someone else. She looked into the distance as she spoke.

Ms Smith reported the encounter to police soon afterwards, and several weeks later she was called in to see a county attorney, Greg Benefiel, the local government prosecutor. She made it clear that she wanted to press charges, she said, but Mr Benefiel saw things differently.

Mr Benefiel said that he would not file a sex charge against Stolzenburg but instead charged him with aggravated battery. Mr Benefiel did not return requests for comment for this article.

In 2020, Stolzenburg was sentenced to two years' probation and required to pay $793 (£590) in restitution, which was paid to a victims' compensation board.

A new legal path

After the prosecutor refused to bring forward a rape charge, Ms Smith decided to use the old law that allowed her to convene a grand jury. Her mother had heard about it while listening to a podcast.

In most of the US, only a judge or a prosecutor has the power to convene a jury, but Kansas, along with Oklahoma, Nebraska and three other states, allows citizens themselves to call one.

To do so in Kansas, a state resident must circulate a petition to collect a certain number of signatures. It varies from county to county, but is calculated based on the number of people who voted in the most recent governor's election. A petitioner must collect signatures equalling at least two percent of the number votes, plus 100 more.

Copies of Ms Smith's petition were posted in bars and cafes in town, and after several months, she had enough names.

Members of grand juries are drawn from a large pool of people, chosen from individuals who have obtained a driving licence or are registered to vote.

The members act like police officers, examining evidence. Sometimes, they subpoena documents from the accused. Other times, they look only at the evidence that the police officers have gathered.

For that reason, they do not call either the accuser, or the accused before them.

The Kansas law dates back to 1887, and was designed to ensure that people who do not have wealth or power can still have a shot at holding someone accountable for their actions.

"It's a way to make sure that every citizen has access to the legal system," said John Mullen, an associate professor of philosophy at Bethany College.

Citizens' grand juries in Kansas have previously been convened because people were unhappy with public art, considering a sculpture to be indecent, or they demanded investigations of doctors who provide abortions.

But it does not seem as though one has ever been called to decide on whether to press charges for a sex crime.

The jury has 60 days to conduct their investigation in closed, confidential proceedings.

If charges are filed, the case is handled as a standard criminal matter. The defendant pleads guilty or not guilty in a traditional jury trial.

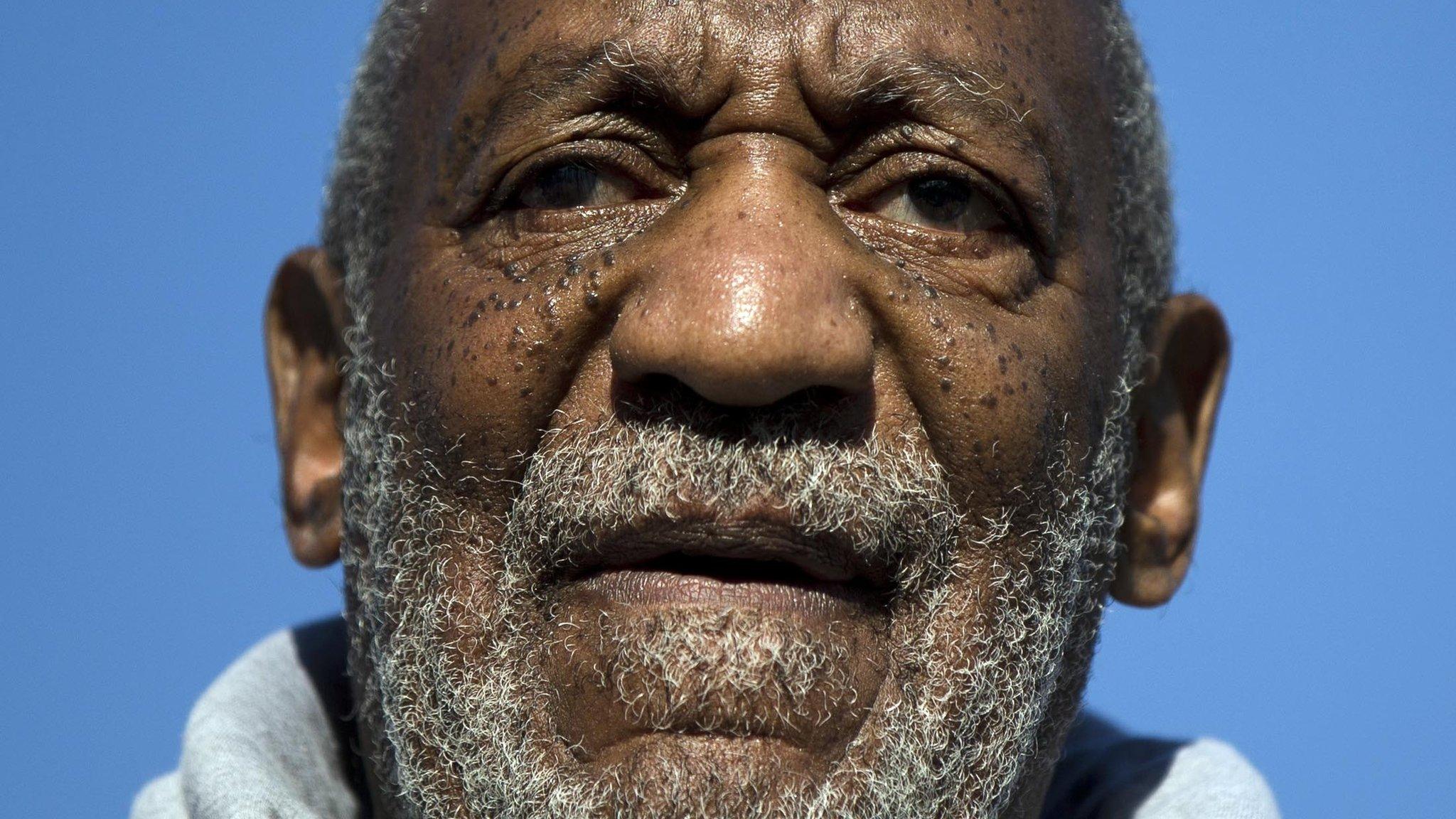

Jared Stolzenburg

A debate over consent

Ms Smith is now married, and works as a medical assistant in a family healthcare centre. She has become a recognisable figure in Lindsborg, her hometown, a secluded place surrounded by wheat fields.

Sitting at a bar on Main Street a few nights before the grand jury convened, she reflected on the events of the last three years.

"He was trying to hurt me and hurt me really badly, and in a way he did that," she said of Stolzenburg. "But I also came back fighting, and I don't think he saw that one coming."

Some have applauded Ms Smith's efforts to push for a citizen's grand jury, and believe that it will help strengthen the resolve of others who have gone to the police, saying they have been raped or sexually assaulted.

Caroline De Filippis, an activist in Lindsborg, said women needed more protection. "A lot of cases around lack of consent are still dismissed, or not even brought to justice, because they don't have 'enough' [evidence]."

"The definition of consent is still very broad," she added, "and it does not show an understanding of what it means to be sexually assaulted."

Others, however, warn that such a system could be easily abused. Laura Kipnis, author of Unwanted Advances: Sexual Paranoia Comes to Campus, said that investigations into sex crimes on campus pose an array of problems.

The incidents take place in private, and it can be exceedingly difficult for members of a grand jury to reach a conclusion. "It's mostly impossible," she said. "They're guessing."

The investigations can also be devastating for the men who are accused, she said, even when they are exonerated: "People's lives are wrecked."

Stolzenburg's life has certainly been upended. His voice on the phone was strained, sometimes breaking as he fought back tears. He was suspended from Bethany after the attack for violating the university's student code and lost his job at a record company.

"Back then, I was 19 and I was new to sex and to intercourse," he said. He said his assault on Ms Smith was an attempt to act out a "sexual kink" he'd seen on the internet.

"I thought it would be something to try, and I was stupid to try it," he said.

Related topics

- Published13 July 2015

- Published31 March 2023