Mass shootings: What are the warning signs and could they help prevent another Parkland?

- Published

In 2019, an attack on two mosques in New Zealand shocked the world

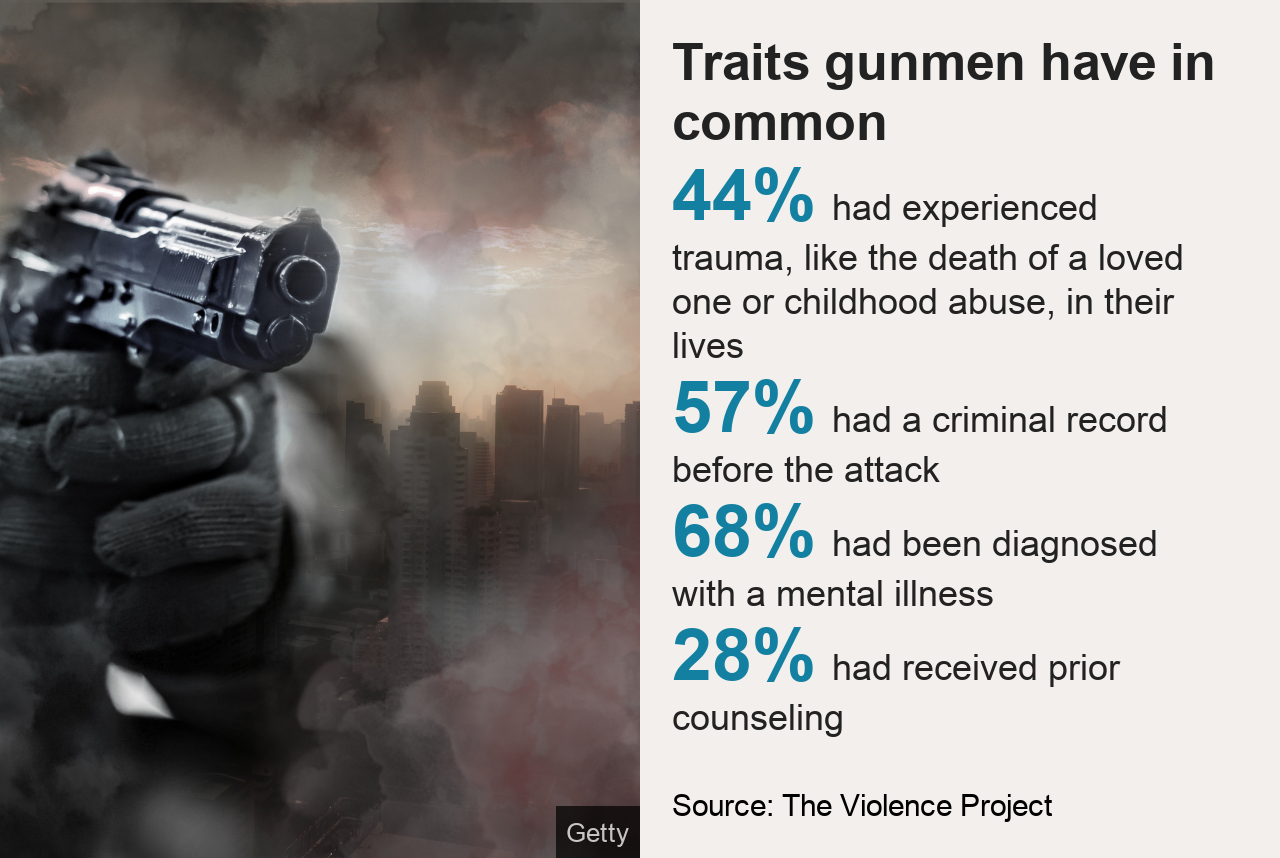

Prosecutors in a high-profile US school shooting case have argued that the gunman should get the death penalty. While each mass shooting in the US is its own tragedy, experts say the killers share many things in common. Could identifying these traits help stop the next attack?

In the days and months leading up to the attack in Parkland, Florida, the killer listened to the same song on repeat: "Pumped up kicks," by Foster the People.

The song's plucky, whistle-tuned melody clashes with lyrics about a bullied teen who seeks revenge by shooting up his school.

In a note on his phone, in which the 19-year-old wrote about his plans to attack, he complained of being "agitated" and said he felt his life was "unfair".

"Everything and everyone is happy except for me," he wrote.

On Valentine's Day 2018, Nikolas Cruz opened fire at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, where he had once been a student, killing 17 people and injuring 17 others.

After his arrest, he pleaded guilty 17 counts of murder and 17 counts of attempted murder.

A jury is deciding whether the now 23-year-old should be sentenced to death. The case is the deadliest mass shooting to reach a jury trial in US history.

Lead prosecutor Mike Satz described the gunman as "cold, calculated, manipulative and deadly", and said the brutality of his crimes far outweighs any mitigating factors, which makes the death penalty warranted.

"Life in prison is a life, and he deserves nothing more than the death penalty," said Gena Hoyer, mother of Luke, one of the victims.

Cruz's attorneys hope to spare him the death penalty by portraying a young man in crisis - his mother had died just before his crime - and who was denied the support he desperately needed.

Whatever the jury's decision, the trial has raised questions from many about what could have been done to prevent the tragedy. Among them, are researchers and analysts who say that Cruz's trajectory towards violence is not unique - but rather part of a common pattern often seen in the lead-up to mass shootings.

Is there a pathway to violence?

Mark Foster, lead singer of the band that the Parkland gunman was listening to on repeat, once said that he wrote "Pumped Up Kicks" as an attempt to understand the link between the rise in teenage mental illness and gun violence.

"I was scared to see where the pattern was headed if we didn't start changing the way we were bringing up the next generation," he told CNN in 2012. He said he is considering retiring the song.

In the five years since the Parkland massacre, there have been more than two dozen mass shootings in the United States. In the aftermath, shock and grief often give way to divisive arguments over gun laws.

But experts say the psychological and social factors of mass shootings are just as important. They have been asking: What drives someone to commit a mass shooting?

"There's a pathway to this type of violence," said James Densley, a sociologist and co-founder of the Violence Project, a non-profit research programme aimed at better understanding mass shootings.

The Violence Project has collected data from police reports, online manifestos and interviews with those closest to the gunmen in over 180 attacks, dating back to the 1960s.

It has found an eerily similar trajectory among these, from childhood trauma, to run-ins with the law, a desire to end the life of the subject and then, finally, a tragic desire to end the lives of others.

A "switch" clicked in his brain, said the sister of a gunman studied by the project. "What is wrong with me?" became "What is wrong with them?"

The reason gunmen are almost exclusively male, Mr Densley added, is likely due to the fact that men are more prone to externalise their feelings, and take out their anger on others.

"It's a way of saying, 'Hey, look, world, this is what you made me do,'" he said.

Mr Densley said one could look at mass shootings as organised "deaths of despair", a term sociologists often use to describe suicides and overdoses. All three have been on the rise over the past 20 years.

He doesn't believe that's a coincidence, but a consequence of society where it's all too easy to fall through the cracks. And these feelings of despair and isolation can be easily weaponised online.

Christchurch and the online radicalisation

In 2019, a gunman opened fire on two mosques in Christchurch, New Zealand, killing more than 50 people in an attack that shocked the world.

The gunman posted his intent and live-streamed the massacre on an online forum.

"There's a goldfish bowl effect where if you have a bunch of people online, and they're not doing well, they will reinforce all the worst things about their behaviour," said Dale Beran, a writer who specialises in reporting on the darker corners of the internet.

Mr Beran has charted how anonymous image boards that champion unfettered free speech went from online spaces where people shared memes and perfected the art of trolling to breeding grounds for several political movements, from the hacktivist collective known as Anonymous, to the groups who stormed the US Capitol.

The nihilistic, antisocial culture of these websites also made them the perfect incubators for disaffected and radicalised young men to graduate from posting violent fantasies online to enacting terror in real life.

Perpetrators of shootings in Christchurch, New Zealand; Charleston, South Carolina; and El Paso, Texas all frequented these forums.

"They are a bunch of powerless men, idolising violent power fantasies. After years of talking about how angry they are, how powerless they are, and how they should get revenge on society which didn't accept them - one of them will go out and do it," Mr Beran said.

Research has shown, Mr Beran says, that one of the best ways to interrupt this cycle of violence is by stopping people from going too far down the internet rabbit hole to begin with.

The Redirect Method

Five days before the Parkland massacre, Cruz's phone history shows he took a screenshot of a psychology article about "homicidal thoughts and urges", and searched for a therapist.

According to Moonshot, an organisation founded to study and interrupt online threats, Americans who are "consuming extremist or violent content online are 47% more likely than the general public to take up offers of mental health services online".

These statistics provide insight into how to reach those considering violence as a way out, Moonshot has said. Vidhya Ramalingam, its chief executive, said that it has got more than 150 people at risk of domestic violent extremism in the US into text-message counselling sessions.

The Parkland shooter attacked his former school on Valentine's Day in 2018

"Any kind of intervention directed at a shooter, needs to take an approach of, 'We're here to help you cope with everyday life'. Because that's really the driving force behind the shooters," said Chris Simmonds, a manager at Moonshot.

He cautioned this doesn't mean people with mental health problems are more likely to commit acts of violence, but it does indicate how receptive those considering violence are to getting help.

The company has also worked with Google Jigsaw and other tech giants to launch "The Redirect Method", which returns alternative, de-escalating search results when people look for harmful content online.

Moonshot believes these kinds of technological interventions, coupled with mental health resources, and a nationwide push for bystanders to report troubling behaviour before it escalates to violence, can help reduce the frequency of these attacks.

"There's like a whole host of other things people need to be doing - governments and organisations - at a much bigger scale to in good faith say we're doing everything we can to prevent senseless acts of violence," Mr Simmonds said.

Seeing ghosts

In hindsight, people often describe perpetrators of mass violence as "ghosts" - they went to school, attended classes, but they had no connections to anyone, no meaningful relationships with the larger community.

The Center for Targeted Violence Prevention (CTVP), a non-profit research institute, has been studying data from averted school shootings since 2016. Its research has shown that there are clear warning signs when someone is getting ready to commit violence, according to its director Frank Straub.

In school shootings specifically, would-be perpetrators might suddenly withdraw from their family and friends. They may start to fantasise in their diary or sketchbook about violence, and they may start searching for violent videos online.

In data from the Violence Project, which looked at mass shootings in all settings, 80% of attacks were preceded by a crisis of some kind.

As soon as these warning signs appear, it's imperative that parents, teachers or other people close to the person take action, Mr Straub said.

"We have to look at it as an emergency situation just like we would somebody who's exhibiting the signs and symptoms of cardiac arrest, we need to, in essence, dial 911," he said.

That's not possible if people in the community fall through the cracks.

In partnership with Michigan State University, CTVP is running a pilot programme in five communities in the state to provide intensive support to high-risk/high-need adolescents and their caregivers. These youths have already been identified by law enforcement for making threats, but have yet to commit an act of mass violence.

Mr Straub said it's important that at-risk youth aren't stigmatised, and aren't treated as merely criminals, but are provided long-term care and support.

"We've heard shooters [say]: 'If somebody had just recognised me, and somebody had just reached out to me, if somebody had just talked to me, if somebody had shown me that they cared, things may have been different'," he said.

"We see so many people that are struggling with loneliness and hopelessness, feelings of helplessness… maybe we just need to extend the hand."

Related topics

- Published23 August 2022

- Published18 July 2022

- Published15 July 2022

- Published17 December 2024