Will the Parkland gunman get the death penalty?

- Published

More than four years after a gunman killed 17 people during a mass shooting at a school in Parkland, Florida, a state jury must now decide whether he should be put to death.

Nikolas Cruz, now 23, pleaded guilty to the murders - as well as 17 counts of attempted murder - in October.

His life rests in the hands of the jury's seven men and five women.

If carried out, Cruz's death penalty will be one of only a handful of executions actually carried out every year in the US, where over 2,000 people are on death row. The US remains the only Western nation to allow capital punishment.

Here's what we know about Cruz's sentencing trial and the death penalty in the US.

How will the jury decide if the gunman should get the death penalty?

Unlike Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the man convicted of the 2013 Boston bombings who was sentenced to death in a federal court, Cruz is facing local charges in the state of Florida.

Under state law, the jury must vote on a sentence for each of his victims. In order to recommend the death penalty, the jury must agree unanimously.

In most criminal cases in the US, a jury determines culpability, and a judge decides on the punishment. But in this case, the jury will decide how he is sentenced.

If they don't give him the death penalty, the only other possible outcome for Cruz is life in prison without the possibility of parole. As per state law, however, the judge would still be able to sentence him to life in prison, even if the jury recommends that he be put to death.

In Florida, prosecutors can seek the death penalty in cases where the accused has been convicted of first-degree murder with aggravating factors, which include previous felony convictions, murders that are "especially heinous, atrocious or cruel", creating "a risk of death to many persons" and "cold, calculated" murders that were premeditated.

During the trial - which is expected to last several months - prosecutors will seek to demonstrate the aggravating factors and premeditated nature of the shooting and its grisly outcome. This is likely to include eyewitness testimony from survivors and video taken at the crime scene, as well as a possible visit to the school.

The defence, for their part, is expected to argue that Cruz was plagued by mental illness and a difficult childhood and does not deserve to be executed.

What states have the death penalty?

A total of 27 states still have the death penalty on the books, including three - California, Oregon and Pennsylvania - which have called for a moratorium on executions.

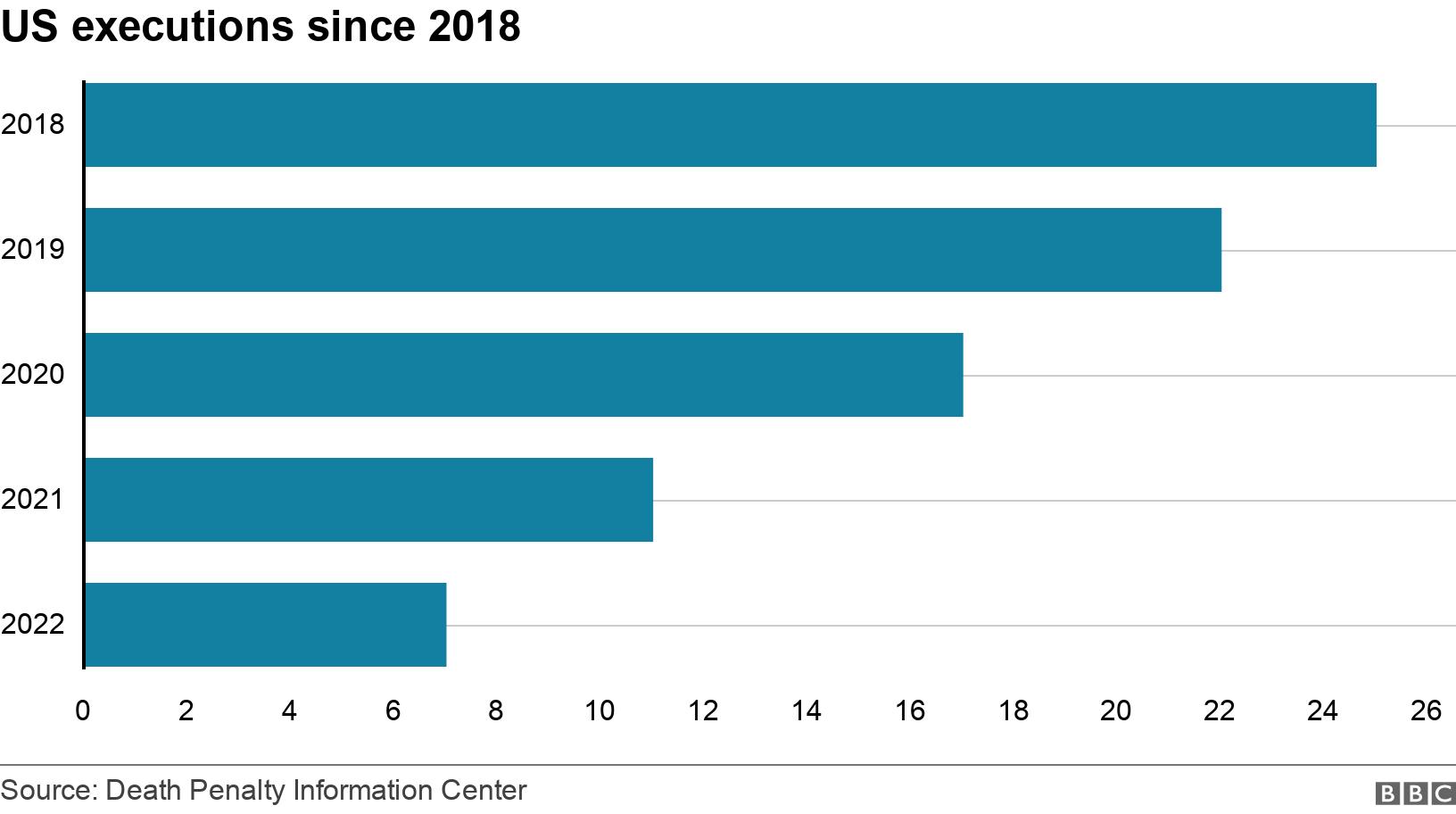

So far this year, seven people have been executed by five states. The most recent execution saw a 66-year-old man put to death in Arizona for the 1984 murder of an eight-year-old girl.

The annual number of executions has fallen over the past several decades since the death penalty was reinstated in 1976 following a four-year hiatus brought on by a Supreme Court ruling.

It decreased from a high of 98 executions in 1999 to just 11 in 2021, according the Death Penalty Information Center (DPIC), a Washington DC-based advocacy group that is opposed to capital punishment.

DPIC's deputy director, Ngozi Ndulue, told the BBC that the US has seen "really significant, continued erosion" in the use and acceptance of the death penalty, largely because of concerns about innocent people being executed or that the death penalty is disproportionately applied to racial minorities.

The vast majority of executions take place in the US south.

Of the 35 executions carried out since the start of 2020, the largest number - seven - took place in Texas.

Harris County - centred on Houston, Texas - has alone accounted for more than 280 death sentences and 127 executions since the early 1980s.

"There is a huge geographic disparity in the death penalty," said Michael Benza, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University in Ohio and attorney who has represented death row inmates. "It is primarily, but not exclusively, a southern institution."

Who is most likely to be executed?

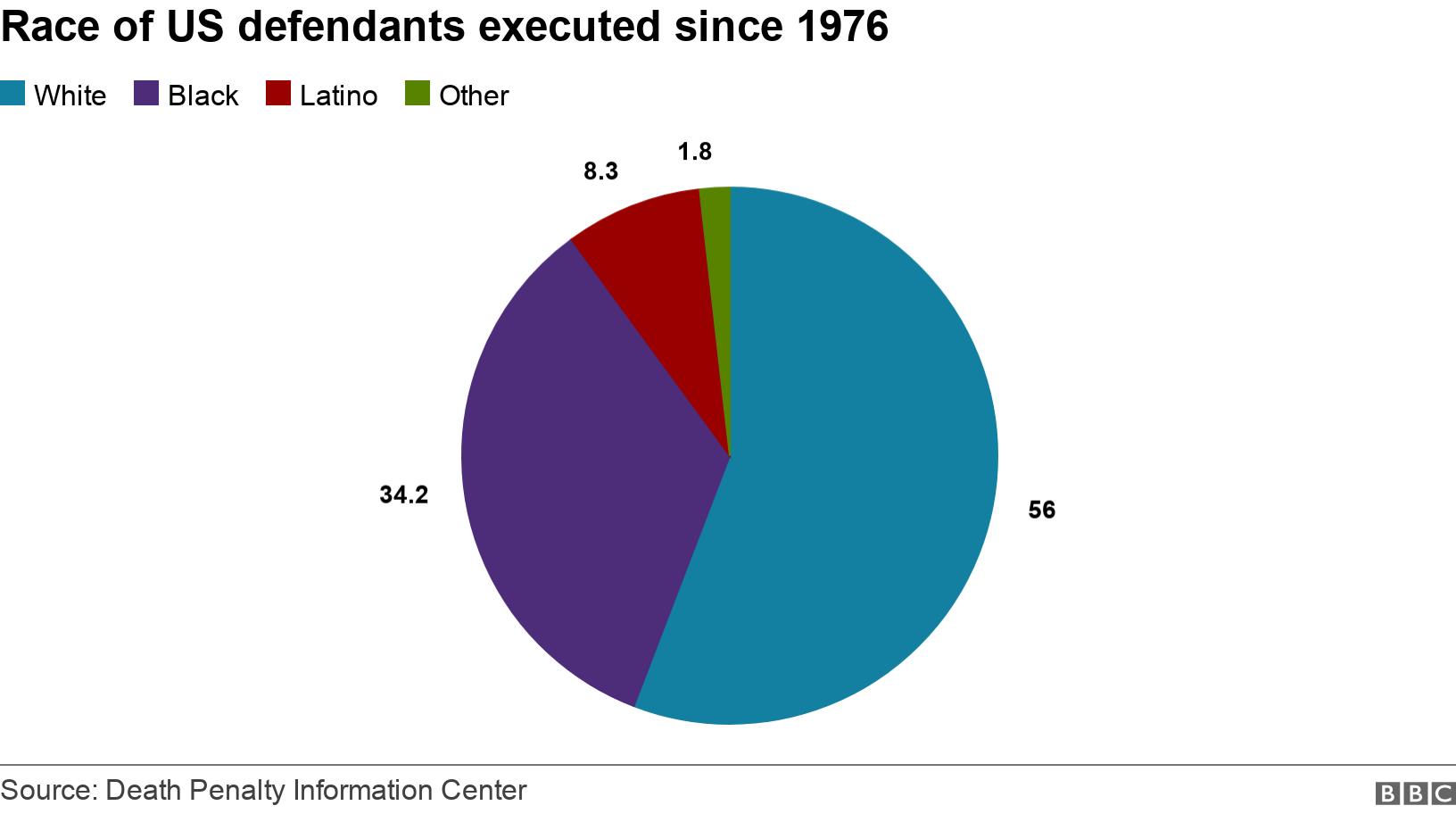

According to statistics from DPIC published earlier this year, 41% of the people still on death row are black and 42% are white, despite the fact that black people make up about 12.4% of the US population.

Ms Ndulue said that the race of the victim is among the strongest factors in the application of the death penalty. Over 75% of the victims in murder cases that have resulted in executions have been white, statistics show.

"If the victim is white, you're much more likely to get a death sentence," she said.

In Washington state, for example, research published in 2014 suggested that jurors were three times more likely to recommend a death sentence for black defendants than for white ones.

What crimes warrant a death penalty?

While all the prisoners currently on death rows across the US have been convicted of murder, each US state has their own rules about capital punishment, who can get the death penalty and why.

In Texas, for example, prosecutors can seek the death penalty in cases where the accused has been convicted of homicide with aggravating factors, which range from murders committed for money or during an attempted kidnapping to the murders of police officers, firefighters or prison guards.

Six other states - including Texas and Oklahoma - also have laws on the books that allow for the death penalty to be sought in cases in which a minor was raped. To date, however, no death sentences have been handed down or carried out for this crime.

In 2008, the US Supreme Court ruled that the death penalty is unconstitutional in cases where the victim did not die, and death was not intended.

How are people executed?

Lethal injections have been, and remain, the most common form of executions in the US, and were used in most executions that have taken place since 1976. In most states, it remains the only method available.

A now dismantled lethal injection room in California in 2019

Some states, however, use other methods. In Arkansas and Florida, for example, inmates can be electrocuted if they submit a request in writing. Other states, such as Utah and Oklahoma, authorise firing squad deaths as methods of execution in cases where lethal injections are not available, or if sentenced before a certain date.

Later this year, South Carolina plans to execute convicted murderer Richard Moore by firing squad, which would mark the first time the method would be used anywhere in the US since 2010. In another case, the Supreme Court ruled in June that a Georgia inmate can die by firing squad after he argued that his veins were "severely compromised" and that he would suffer if given a lethal injection.

While state authorities have argued that lethal injections cause less pain and suffering than other methods, critics have argued that it possibly constitutes "cruel and unusual" punishment that would be contrary to the Eighth Amendment of the US constitution. The debate has seen intense legal wrangling and in 2015 reached the US Supreme Court, which ruled that condemned prisoners can only challenge the method with which they'd be executed if a viable alternative is provided.

Does the federal government execute people?

Just several months after US President Joe Biden took office, Attorney General Merrick Garland ordered a pause on federal executions, which had been restarted by the Trump administration in 2020 after a 17-year hiatus.

All told, 13 federal inmates were executed during the Trump administration. Before then, only three people had been executed since the federal death penalty had been reinstated in 1988, all during the George W Bush administration in 2001 and 2003.

Mr Garland, however, has come under pressure to make the death penalty available in the case of Payton Gendron, a suspected white supremacist charged with murdering 10 people in Buffalo, New York, on 14 May.

In March, the US Supreme Court re-imposed the death sentence for convicted Boston marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, reversing an earlier appeals court ruling that voided it, arguing the judge in his original trial had failed to question potential jurors about how much they'd been following the case in the news.

Earlier in the year, then-White House spokeswoman Jen Psaki said that the Biden administration has "grave concerns" about whether the death penalty "is consistent with the values that are fundamental to our sense of justice and fairness".

The justice department, however, has defended the death sentence for Tsarnaev. Mr Garland's moratorium did not prevent prosecutors from continuing to seek capital punishment in the case.

Related topics

- Published18 July 2022

- Published2 July 2021

- Published20 April 2021

- Published11 April 2017