Why Trump loyalist went to prison rather than blame the boss

- Published

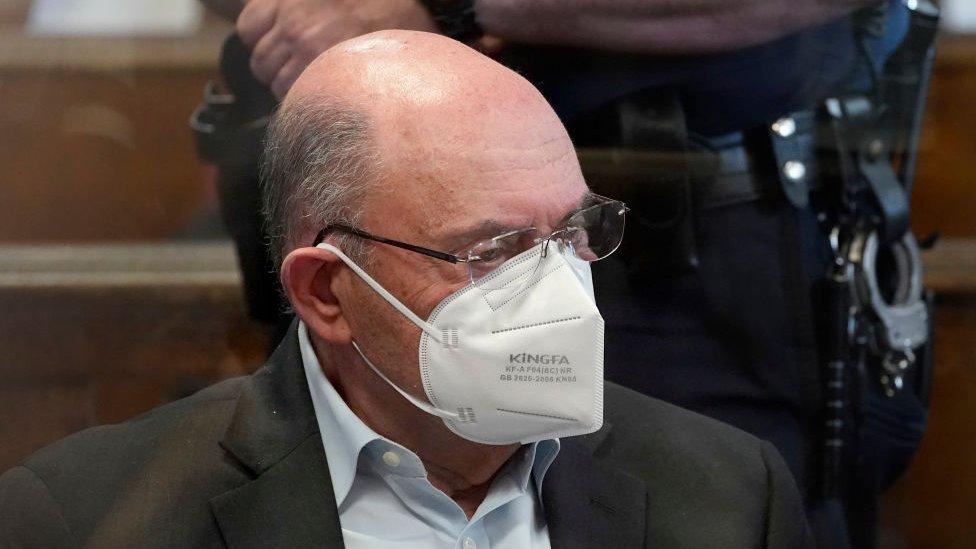

Allen Weisselberg worked for former President Donald Trump for decades (file image)

Former US President Donald Trump's long-serving chief financial officer, Allen Weisselberg, has been sentenced to five months in jail for his role in a tax fraud scheme.

Weisselberg, 75, was given a shorter-than-expected jail term after agreeing to a plea deal in which he served as a prosecutor's witness against the Trump Organization.

But Mr Trump had little reason to fear that Weisselberg's testimony in the autumn trial would harm him or overshadow his announcement in mid-November that he was launching another run for president.

Indeed, as expected, his employee - who started with his father Fred Trump and who was one of the first to join his company in 1986 - remained loyal even under immense pressure.

While Mr Trump sounded off on social media, pinning the fraud scheme on Weisselberg, he continued to offer him his support in arguably more meaningful ways. Jurors heard how the Trump Organization was still paying Weisselberg his same salary under the title senior adviser, covering his legal fees, and recently celebrated his birthday in the office.

"In a normal organisation, a corrupt CFO would be terminated and thrown out the door," says Professor Maurice Schweitzer from the Wharton School of Business. "And you would want to separate and preserve the integrity of the institution. In this case, it's the exact opposite."

The trial provided a fascinating insight into the relationship between the loyal lieutenant and his boss - as well as prosecutors' efforts to try to turn one against the other by threatening Weisselberg with a lengthy sentence at Rikers Island.

Weisselberg is expected to report to the notorious New York prison to begin serving his sentence immediately.

His attorney, Nicholas Gravante, said after Tuesday's hearing: "He deeply regrets the lapse in judgment that resulted in his conviction, and he regrets it most because of the pain it has caused his loving wife, his sons and wonderful grandchildren."

Under the plea deal, Weisselberg admitted to 15 felonies including tax evasion, and must pay nearly $2m (£1.65m) in fines in addition to the five-month prison term.

But without the deal, he could have faced as much as 15 years in prison.

But despite prosecutors' focus on Mr Trump, Weisselberg refused to co-operate with the wider investigation into the former president and his business practices.

The question of what Mr Trump potentially knew about executives deceiving the tax authorities and not properly reporting benefits became a persistent and tricky one throughout the trial given he was not personally charged with wrongdoing.

Weisselberg prepared for his testimony with both the prosecution and the defence, an unusual arrangement. The Trump Organization's lawyers repeatedly argued during the trial that he was motivated by greed, and that "Weisselberg did it for Weisselberg". The defence strategy, in a nutshell, was that the former CFO was not shown the door because he was regarded as a family member, "a prodigal son".

Prosecutors throughout the trial carefully tried to extract concessions from Weisselberg to bolster their case, while also poking holes in his story that Mr Trump and the business knew nothing of his 15-year tax dodging scheme. They walked the jury through how Weisselberg joined Mr Trump from day one and rose from accountant to controller to CFO. He had deep knowledge of all of the financial workings of the business as it grew. His testimony was key to exposing corruption and fraud at the Trump Organization and gave insight into how the family operated.

On the stand, he teared up as he was asked: "Did you betray the trust that was placed in you?"

"I did," he answered.

Defence lawyer Alan Futerfas continued: "Are you embarrassed by what you did?"

"More than you can imagine," he replied.

The man who Mr Trump once described as tough to contestants on an episode of The Apprentice, his old reality show, appeared timid and nervous.

Weisselberg during the trial in New York.

A source close to the case insists Weisselberg's testimony under oath was truthful and that he chose not to make up stories about Mr Trump. "That's just common moral decency. And it's also consistent with the rule of law, you should not make up lies about someone and then offer to give that testimony, which is perjury, just to improve your own legal situation after you have messed up in order to try to get a reduced sentence," the source told the BBC.

His determination to take blame, however, did not convince the jury, which unanimously decided to convict the Trump Organization. Nor did it convince former federal prosecutor Mitchell Epner, who got the impression that the 75-year-old was very scared. "He was hoping to be able to placate Donald Trump by his testimony. And I took those tears to be self-pity for fear that he is going to be frozen out of Trump World," said Mr Epner.

Prof Schweitzer says the dynamics at play in this trial were in line with Mr Trump's management style, what academics refer to as a "dominant" leader.

"There's broadly two kinds of leaders, there are leaders who gain status because of their expertise and wisdom and capabilities, and there are leaders who maintain their positions of power because of dominance," says Prof Schweitzer.

"Basically, they pull levers of rewards and punishments to coerce or compel people to do what they want."

Mr Trump has been successful throughout his business and political career figuring out "loyalty levers to reward friends and hammer foes", says Prof Schweitzer.

The former president has a history of rewarding those who stand by him and attacking those who don't. Before he left office, he pardoned several of his former aides of their convictions, including his National Security Adviser Michael Flynn, his ex-adviser Roger Stone and his former campaign chairman Paul Manafort.

On social media, President Trump praised Manafort for not "breaking" like his former lawyer Michael Cohen. Cohen and Manafort's deputy Rick Gates were convicted in the Mueller probe into Russian interference in the 2016 election, but both co-operated with prosecutors. They, to the surprise of no-one, did not get pardons from Mr Trump.

Weisselberg stands behind Mr Pence and the former president at Trump Tower in New York in 2017

The former president's treatment of Mike Pence is another example of how he places loyalty above other values. Mr Trump reportedly told the former vice-president not to "wimp out" and to not certify the results of the 2020 election, according to an excerpt from Mr Pence's book. He recounts Mr Trump asking him: "If it gives you the power, why would you oppose it?"

Prof Schweitzer says both Mr Trump and Weisselberg were shaped by the era of '80s New York and the mindset that greed is good. "Greed was celebrated and endorsed in a way that it is not today, we had different mindsets about this wild west of capitalism," he says. "Things that we are saying are illegal were common practice. These men really enjoyed the privileges that came with being a very powerful, wealthy person in the 1980s who were not constrained by the rules that bound the rest of us."

Mr Epner agrees. "The New York real estate business has been a dirty business for not decades, but centuries. And he [Mr Trump] was part and parcel of the dirty part of the NY real estate business and then he shone the biggest spotlight in the world on himself [with the presidency]."

On the final day of the trial, Assistant Manhattan District Attorney Joshua Steinglass said during closing statements that the evidence had shown that Mr Trump knew exactly what was going on. He reminded the jury of that evidence, including a memo the former president initialled authorising a pay cut for another executive for the exact amount of his perk, rent paid by the company.

"Mr Trump explicitly sanctioning tax fraud! That's what this document shows," Mr Steinglass said.

To many, it begged the question why the former president, who built his entire reputation and bravado off the back of his namesake company, wasn't charged, too. The Manhattan District Attorney's office says investigations into Mr Trump are ongoing.

Related topics

- Published28 August 2024

- Published6 December 2022

- Published18 August 2022