The ancient trees at the heart of a case against the Crown

- Published

A small indigenous community is fighting a historic land rights claim in Canada - and they are using ancient trees and famed British explorer Captain Cook's journal to help make their case.

Wearing her red cedar hat and with a microphone in hand, Mellissa Jack stood in front of the British Columbia Supreme Court on a warm autumn day with a message.

"We have proven who we are, where we come from, and we are not going anywhere," she called out, to cheers from a gathered crowd.

In September 2022 Ms Jack and about 100 others had travelled from all over the province of British Columbia (BC) to be together outside the court as hearings in a closely-watched land rights case being fought by their indigenous community - Nuchatlaht First Nation - were drawing to a close.

The Nuchatlaht case not only has significance for Ms Jack and her people, but is being watched for its potential impact on indigenous land claims in Canada and what it means for the provincial government's commitment to reconciliation.

As one expert put it, the decision could be "the first tile in the Aboriginal rights game of dominos".

And to help win their case, the Nuchatlaht are using a unique piece of evidence that they say is not only a part of their cultural heritage, but also an important living artefact that must be cared for to restore a damaged land.

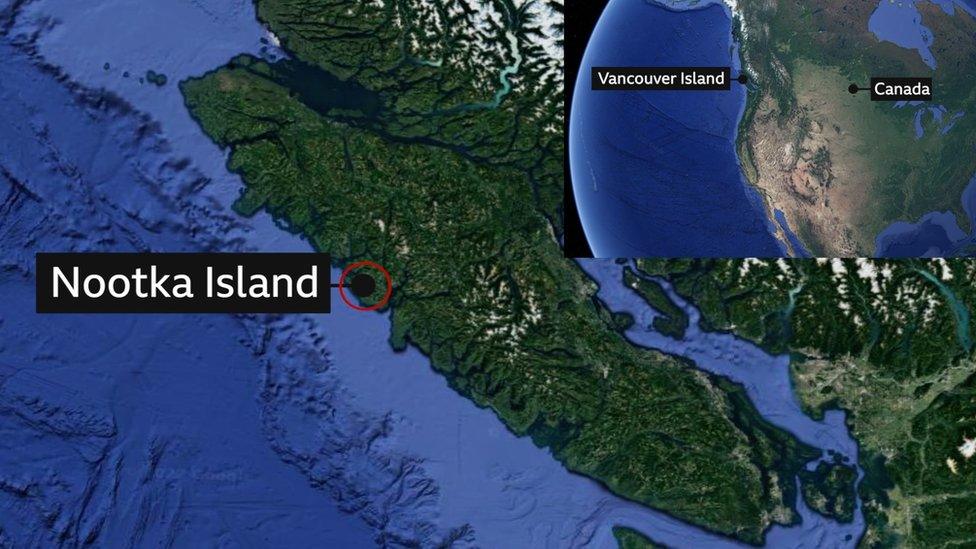

The Nuchatlaht filed the lawsuit against the province in 2017, claiming rights and titles of approximately 200 sq km [20,000 hectares] of land in the northern part of Nootka Island on the western edge of Vancouver Island.

The Nuchatlaht say they are the rightful stewards of the land, that it has been theirs for thousands of years and they have never surrendered it.

The Crown, which now owns the land, has denied the Nuchatlaht claim, and has argued that the Nuchatlaht have no continuous connection to the territory.

A lawyer for the Nuchatlaht has argued that the community was forced from their land by - among other causes - the creation of the reserve system in Canada, land set aside by the federal government for the exclusive use of First Nations.

"Canada put us aside on a little chunk of land with no value and no resources. That's why we are fighting in court right now, fighting for what little is left," Jordan Michael, Chief of the Nuchatlaht, told the BBC.

To win, one of the things the Nuchatlaht must prove is that they continuously and exclusively occupied the land in 1846, when Britain gained sovereignty over what is now BC in a treaty signed with the United States.

Members of the First Nation - there are about 160 of them - are confident they will prevail.

"We are small, but we are mighty," said Archie Little, Nuchatlaht House Speaker.

The province would not comment on the case, though it has previously said it respects the right of indigenous peoples to choose how they settle legal issues, including through the courts.

If they win rights to the land, "we would manage it, enhance it, protect it," said Mr Little.

"We need to help heal the earth. We will plant the proper trees and start the healing process. It's a big chore but we're up to it. We want to show that we can own and manage better," he added.

A verdict is expected in the coming weeks.

Ancient cedars in the courtroom

Nootka island is bountiful in natural resources. It is abundant in fish and covered in dense ancient forests. It is home to highly sought-after old-growth red cedar trees that can live for over 1,000 years.

Red cedars can grow to become giants in the forest, and have a distinctive cinnamon red bark. The largest in BC soars 56 metres (183 feet) towards the sky on a trunk base that is six metres wide (19 feet).

These ancient trees were among the most unusual pieces of evidence the Nuchatlaht have presented to prove that their people continuously lived on the claim area on Nootka Island.

They called in archaeologist Jacob Earnshaw to give evidence about what are called "culturally modified trees" - trees that show cultural use by indigenous people, mainly bark harvesting.

"Culturally modified trees are really important," Mr Earnshaw, who was commissioned by the Nuchatlaht First Nation to perform surveys in the claim area, told the BBC.

"Arguments about having title to the land is that you can prove continuity, sufficiency of occupation and exclusivity of occupation and they are a very good tool for proving that."

There are thousands of culturally modified trees across approximately 100 sites in the Nuchatlaht territory. The largest site has 2,700 culturally modified trees showing how lobes of the trees healed around the harvested bark, creating scars that date back centuries.

Ms Jack grew up on Nootka Island. She remembers running in and out of the water, climbing trees, and collecting clams outside her grandparents' house.

"I remember the smell of my grandmother's home - it was cedar wood," said the mother of two and councillor for the Nuchatlaht.

"Cedar trees are a huge part of who we are. They are part of our identity and we need to preserve that," she said.

Her aunt, Lydia, explains how they would harvest long strips of bark from the north side of the tree where it doesn't catch the sun, and make medicines, ceremonial regalia, hats and fishing tools.

If the Nuchatlaht win rights to the land, Mr Little said they would seek to protect it. The province granted forestry licences on parts of the territory and the First Nation says industrial logging has damaged the land.

A look at Captain Cook's centuries-old journals

The First Nation has also relied on Captain James Cook to bolster their case.

In 1778, the British explorer was on his third and final voyage around the world - a mission to find the Northwest Passage across the Arctic.

In a quiet inlet, Cook sat down to write as he looked out across the dense forested landscape and coastal mountains.

He wrote: "King George's Sound was the appellation given by the Commodore to this inlet, on our first arrival; but he was afterwards informed that the natives called it Nootka."

Quoted in court were Cook's writing about how the indigenous people he met on Nootka had "such high notions of everything the country produced being their exclusive property".

"The very wood and water we took on board they at first wanted us to pay for, and we had certainly done it, had I been upon the spot when the demands were made."

In court documents filed in response to the Nuchatlaht claim, BC said that several indigenous groups, including the one that became known as the Nuchatlaht, "at various times" used and occupied portions of the land in question.

But the Crown argued the Nuchatlaht were "relatively small in relation to other indigenous groups in the area" and so had little capacity to prevent others from using the region's land and resources.

A case that could change British Columbia

The Nuchatlaht case will be the first test of a precedent-setting 2014 Supreme Court of Canada decision on indigenous land title in Canada.

That decision granted the Tsilhqot'in First Nation title to more than 1,700 sq km of its ancestral land in BC - the first time in Canada that indigenous title had been confirmed outside of a reserve.

Jack Woodward - lawyer for the Nuchatlaht who also litigated the Tsilhqot'in First Nation case - described Nuchatlaht community as "punching above its weight" with the lawsuit.

"We are expecting to win and that's going to be quite a tremendous step forward for the Nuchatlaht people and really for all indigenous people in Canada," he told the BBC.

If the Nuchatlaht win their case, the many indigenous nations in British Columbia with unresolved land claims will take notice, said Gordon Christie, an associate professor at the Peter A Allard School of Law at the University of British Columbia.

The province has focused on negotiating treaties to deal with unresolved questions over land with First Nations communities in BC.

The Nuchatlaht gave up on their lengthy treaty talks to take the case to court - and others could follow if they are successful.

First Nations would "really dig down and push their cases through and your landscape of BC will change," Dr Christie said.

The possibility is that "sometime in the next 20-30 years, we'll have all these First Nations across BC with substantial pieces of land that they have property rights over," he said. "That'll change the economy and change the way business is done here."

Related topics

- Published27 June 2014

- Published30 November 2016

- Published30 November 2016

- Published30 October 2021