Hamline University professor who lost job over Muhammad art sues

- Published

Hamline University in St Paul, the capital city of Minnesota, was the scene of a fight over free speech and religion

A professor who was let go from her job after showing a class an artwork depicting the Prophet Muhammad has sued her former university, alleging religious discrimination and defamation.

The case has raised issues of religious tolerance and academic freedom.

The basic facts are not being disputed.

Erika Lopez Prater showed a classical work depicting the Prophet in an art history class at Hamline University in St Paul, Minnesota.

One of her students complained, and Prof Lopez Prater's contract was subsequently not renewed at the end of the term.

But the details of the case and the university's response have prompted a wave of debate, media attention and conflicting public statements, culminating in a lawsuit announced Tuesday.

The picture that was shown was an illustration of Muhammad receiving a revelation from the angel Gabriel - part of A Compendium of Chronicles by Rashid-al-Din, a 14th Century Islamic scholar.

Before presenting it, she warned students that they could choose to opt out of the lesson, as many Muslims consider images of Muhammad to be un-Islamic, although there is a variety of views within Islam on the subject.

Despite the warnings, Aram Wedatalla, a student and president of Hamline's Muslim student association, was upset by the class and after a conversation with the professor, complained to university authorities.

"I'm like, 'This can't be real,'" Ms Wedatalla later told the university's student newspaper, external. "As a Muslim, and a black person, I don't feel like I belong, and I don't think I'll ever belong in a community where they don't value me as a member, and they don't show the same respect that I show them."

An administrator then called the professor's actions "Islamophobic" - a label that the university later recanted - and her adjunct contract was not renewed.

The controversy grows

The controversy was mostly confined to academia until the New York Times published a story, external about the incident earlier this month.

A number of academics and groups including PEN America, an organisation that supports free expression, came out in support of Prof Lopez Prater.

Amna Khalid, a history professor at nearby Carleton College, wrote in the Chronicle of Higher Education, external that she was "appalled" by the university's decision and that "it is the students who pay the highest price for such limits on academic freedom."

Prof Khalid, who is Muslim, told the BBC that a number of junior academics in the area have been in touch with her, expressing fear about what they can or can't say in the classroom.

"I don't want to vilify the student," she said. "The problem is the institution."

Depicting the Prophet

Muslim groups were divided. While many civil rights groups came down on the side of the professor, Ms Wedatalla, the student, was initially supported by the Minnesota branch of the Council on American-Islamic Relations (Cair).

But the group's national leaders took a different view. The national Cair organisation has said there was no evidence Prof Lopez Prater was acting with "Islamophobic intent."

Another advocacy group, the Muslim Public Affairs Council, came out with a full-throated defence of the professor.

"Dr Prater was trying to emphasise a key principle of religious literacy: religions are not monolithic in nature, but rather, internally diverse," the group said.

The range of opinion highlights longstanding disagreements among Muslims over the sensitivity of depicting images of the Prophet.

There is no explicit rule against such depictions in the Koran, instead the idea arises in the Hadiths - stories about the life and sayings of Muhammad gathered in the years after his death.

The prohibition is aimed at preventing idolatry - the worship of images in place of a god - and it is thought that classical depictions of Muhammad were only viewed by a select elite.

Sunni Muslims tend to be more strict in their interpretation of a ban than Shia Muslims. For instance, images of the Prophet are more common in Shia-majority Iran.

Prof Lopez Prater said she attempted to address the issue of divergent ideas about representation in religious art during the class.

Controversies of this nature have tended to flare up not in art classes but around displays of cartoons or other drawings by people attempting to make political points or promote specific ideas about freedom of speech.

The debate over the Hamline University incident has been mostly confined to the campus and media debates. But on occasion depictions have led to anger and even violence by Islamist extremists - perhaps most notably the attack against the satirical French magazine Charlie Hebdo in 2015.

University response

Having initially defended its decision and its criticism of the professor, the university backtracked on Tuesday, saying that its use of the word Islamophobic was "flawed" and pledging to hold discussions in the coming months about academic freedom, student care and religion.

"We strongly support academic freedom for all members of the Hamline community. We also believe that academic freedom and support for students can and should co-exist," officials said.

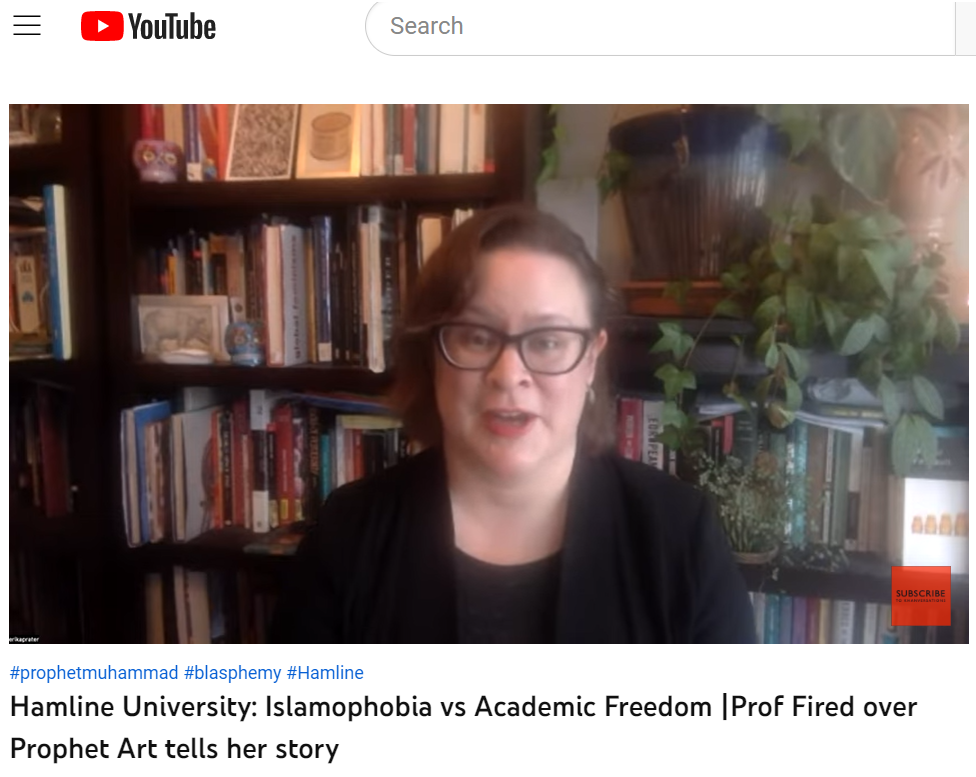

Prof Lopez Prater spoke to an academic YouTube channel

But in her lawsuit, Prof Lopez Prater's lawyers said she had suffered significant damage to her career and reputation.

In her first public comments since the New York Times story, made to a YouTube roundtable discussion on faith, Prof Lopez Prater outlined her thinking in showing the image.

"I was teaching a world art class that was meant to be global in its perspective and think about diversity and global connections throughout history," she said.

Related topics

- Published4 October 2021

- Published15 January 2015