Scot Peterson did not confront the Parkland school shooting. Should he be jailed?

- Published

The case of a former sheriff's deputy on trial for failing to confront the Parkland gunman in 2018 could set a new bar for how police are expected to respond to a school mass shooting.

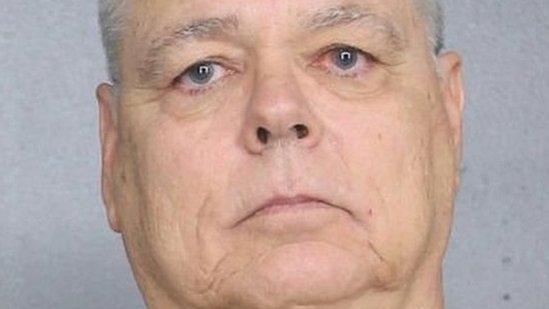

A Florida jury is currently deliberating whether Scot Peterson, 60, is guilty of 11 counts that include felony child neglect and culpable negligence. He has pleaded not guilty.

Mr Peterson's case has added a legal and moral dimension to a fraught national debate over law enforcement's responsibility to protect students during school shootings, which are a common occurrence in the United States.

His trial comes a year after the massacre at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, where authorities faced outrage and investigations after they waited over an hour to enter the school while a gunman murdered small children inside.

Police officers are not legally obligated to sacrifice their lives on the job. But these recurring tragedies frequently place law enforcement in the position of having to defend students and engage directly with armed assailants.

"The entire country is watching this trial," said Bob Jarvis, a legal expert at Nova Southeastern University in Florida. "It is precedent setting. It will tell us, in the form of the jury, what average people expect of cops.

"It is either going to open the door to a floodgate of claims against cops for not rushing in in the future," Mr Jarvis said, "Or it will slam the door pretty tight on the possibility of future prosecutions like this."

The caregiver question

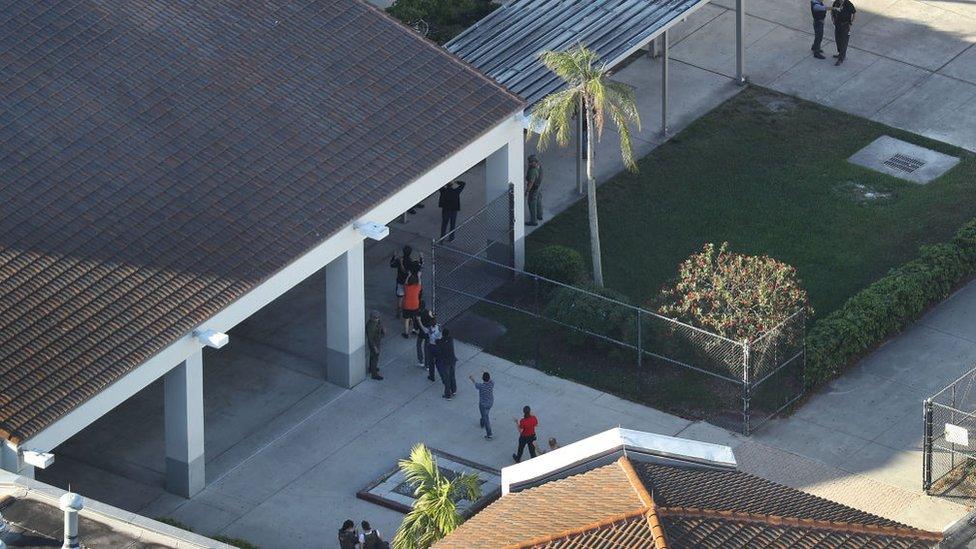

Mr Peterson did not rush inside as 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz rampaged through Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School on 14 February, 2018. Seventeen students and staff were killed, and 17 more were injured.

Mr Peterson arrived at the building with his gun drawn 73 seconds before Cruz reached the third floor of the 1200 classroom building. He took shelter in an alcove outside and waited for help to arrive. He and his attorneys say he did so because he did not know where the shots were coming from.

Florida prosecutors say Mr Peterson, then an officer for the Broward Sheriff's Office, neglected his training and his duty by failing to enter that building while the gunman fired on students. They are seeking to hold him legally responsible for not confronting Cruz, in a case believed to be the first of its kind.

There is no law that requires a police officer to put themselves in the line of fire, or risk their lives during a shooting.

Instead, prosecutors charged Mr Peterson with seven felony child neglect counts for the four student deaths and three injuries that took place on the third floor - once Mr Peterson was on the scene - as well as misdemeanour culpable negligence for three adults who were shot there.

Successfully persuading the jury that Mr Peterson was a caregiver for the children, and therefore obligated to protect them, is key to securing a conviction.

Mr Peterson's lawyer has argued that he was not, in fact, a caregiver.

"He's not a teacher, he's not a parent, he's not a kidnapper who's responsible for the well-being of a child. He's not hired by the school system," attorney Mark Eiglarsh told CNN as the trial began.

Mr Jarvis said that the caregiver case was legally shaky, given its novel application. And even if a jury agreed with prosecutors, he added, the trial judge or an appeals court could decide that Mr Peterson did not actually qualify as a caregiver under the law and overrule the jury's decision.

A new legal frontier

A conviction in the Peterson case opens up an entirely new field of legal quandaries for not just police officers, but other school staffers who find themselves caught up in a mass shooting.

Some states have adopted a controversial rule that allows teachers to carry guns at school. Should Mr Peterson be found guilty of felony child neglect, it could have implications for educators, not just police, one expert said.

"What does that mean for all the teachers who have guns in schools?" said Ron Astor of the University of California Los Angeles and an expert on school violence. "Are they going to be held responsible if they choose not to [confront a shooter]?"

Mr Astor noted that even professional police officers will routinely call for backup in situations they feel they cannot handle alone. He added that not all school resource officers or security guards receive the level of training that would prepare them to confront a shooter with an assault-style weapon.

"Is it a reasonable thing to do for somebody who's not a swat team member, or trained in the military?" he asked.

A "moral obligation"

Legal arguments aside, the case has raised questions about whether a school resource officer, police officer, or other member of law enforcement has a moral requirement to run toward gunfire.

Parkland parents and members of the school resource officer community have criticised Mr Peterson's response.

"Our role in that situation, our obligation, is to go after the threat and do everything we can to stop it," said Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers.

Mr Canady could not speak to Mr Peterson's training or experience, but told the BBC: "I do know I've seen many school resource officers respond in the proper way, which is to attack the problem, not to sit back and wait for the cavalry."

"It is your moral obligation," he said. "When you are sworn in, you're swearing to protect and serve."

While Mr Peterson's case will not end the debate over how to stop school shooters, it will likely serve as a teaching moment for officers who may have to respond to a shooting in the future.

But Mr Jarvis was more sceptical that convicting Mr Peterson would accomplish much reform.

"It is human nature to find someone to blame, and Scot Peterson is an easy punching bag," Mr Jarvis said. It was easier to try Mr Peterson, he argued, than it was to solve the larger, thornier issue of wide access to guns in the US and a lack of mental health resources, particularly for young men and boys.

"There are many, many failures," Mr Jarvis said, "that led to Nikolas Cruz being able to do what he did."

WATCH: 'My son's killer gets to live. That's not justice'

- Published8 June 2023

- Published6 June 2019

- Published2 November 2022

- Published13 October 2022