The fight over a Confederate statue in Arlington National Cemetery

- Published

Authorities say the base of the statue will not be moved to prevent disturbing the graves of Confederate soldiers that surround the monument

A Confederate memorial in America's most honoured cemetery is coming down. But what should be done with it?

When Judith Ezekiel was five years old, her grandfather drove her and her two brothers to Arlington National Cemetery, to see a statue made by their relative.

Moses Jacob Ezekiel, Judith's cousin four times removed, was a renowned Jewish sculptor in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries. His most famous work, what he called the "crowning achievement" of his career, has stood inside Arlington since 1914: the Confederate Memorial.

"My grandfather was quite proud of his artistic prowess," Dr Ezekiel says. At some point in their childhoods, Judith says, he took all 15 of his grandchildren to see Ezekiel's work.

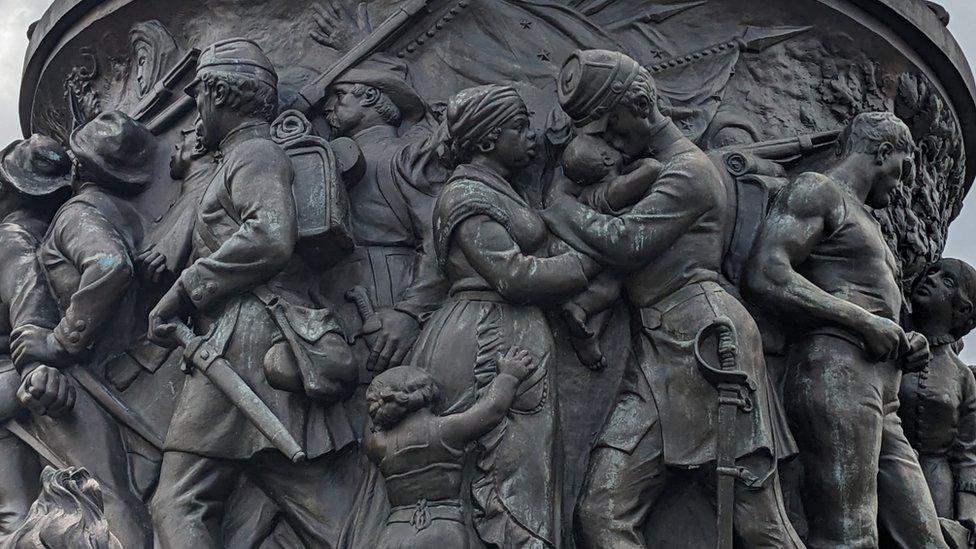

The monument, a bronze statue and plinth on top of a granite base, commemorates the men who fought and died for the slave-holding southern states in the US Civil War.

For more than a century, this statue commemorating the Confederacy has stood inside Arlington - known as America's most sacred shrine. Overlooking Washington DC across the Potomac river, it hosts some 400,000 graves: US soldiers, sailors, astronauts, actors, and even two presidents.

But by next year, by order of the US government, the monument must be removed. The decision is part of an ongoing movement to rethink how the US remembers the Confederacy.

Some 377 memorials have been renamed or removed since 2015. But as of 2022, some 723 remain, according to a report by the Southern Poverty Law Center, external. Hundreds more roads, schools and parks named after Confederate leaders also remain.

As a child, Ms Ezekiel and her brothers went to see the memorial designed and built by her distant relative

Dr Ezekiel, a historian and professor emerita of women's and African American studies, thought little more of the statue until decades after her visit, in 2017.

That August, white supremacists gathered in Charlottesville, Virginia to protest the proposed removal of another statue, of Confederate General Robert E Lee.

Men marched through the streets chanting "Jews will not replace us" and "white lives matter". An avowed neo-Nazi drove his car into a crowd, killing one person and injuring dozens more.

Watching the horror unfold on the news, Judith saw the far right demonstrators near a statue of Thomas Jefferson in the city. "The irony is that it was sculpted by a Jew - it was also sculpted by Moses Ezekiel," she says.

As the violence unfolded in Charlottesville, Dr Ezekiel called her relatives. "What can we do about Moses Ezekiel's monument in Arlington?" she asked.

Her distant cousin had fought for the Confederacy. He was determined to build a monument to correct what he believed were "lies" told about the South.

His statue features a stereotypical depiction of a black woman, handing a baby to a southern soldier. Scholars view it as an artistic representation of the once popular idea that the war was a "lost cause", not about slavery, but instead a just fight for state's rights. Historians now largely view this explanation for the war as a myth, spread to cast the Confederacy in an honourable light, and to mask the brutality of the country's slave-owning past.

Moses Ezekiel himself said he wanted to "correct" the history of the South with this statue, and added a stereotypical depiction of a black woman

Within days, a public letter, external signed by Dr Ezekiel and dozens more relatives of the sculptor appeared in the Washington Post. Moses Ezekiel's family wanted his famous Confederate memorial removed.

"Like most such monuments, this statue intended to rewrite history to justify the Confederacy and the subsequent racist Jim Crow laws. It glorifies the fight to own human beings, and, in its portrayal of African Americans, implies their collusion.

"As proud as our family may be of Moses's artistic prowess, we — some twenty Ezekiels — say remove that statue. Take it out of its honored spot in Arlington National Cemetery and put it in a museum that makes clear its oppressive history."

"It was a protest," Dr Ezekiel says. "There's this blemish in the family history, which is that the Ezekiel line goes back to southerners, some of whom were Confederates, and at least one of whom, it turns out, owned a human."

Now the family have seemingly got their wish. In the wake of the murder of George Floyd, the US Congress set up the Naming Commission, a group tasked with making a list of monuments and names that honour the Confederacy, and recommendations for what to do with them.

Last year, the body announced its findings - among them, an order to remove the Confederate memorial in Arlington. Only its granite base will remain, so surrounding graves are not disturbed.

The statue is based on the far western side of the cemetery. Dozens of graves surround it, including that of Moses Ezekiel himself, marked with a metal plaque right by the base of the statue.

According to Arlington spokesperson Kerry Meeker, it's not a common stop for tour groups, partly because it is located far from the site's main entrance.

Some, however, have visited recently. One grave for a Confederate sailor has a clean white naval cap placed on top of it.

The decision to remove the statue has already proved controversial. The cemetery reportedly received, external some 300 written responses about the monument within months of the removal order.

Some opposed to the statue's removal are now suing the US Department of Defense over the plan. According to the suit, the plaintiffs want to stop the "illegal, arbitrary and capricious decision to tear down and remove, and thereby desecrate" the memorial. They say the statue has "extraordinary significance to American history and cultural heritage".

LM Siegel is a member of Defend Arlington, a campaign group that is part of that lawsuit. She fears removing the statue could set a precedent.

"Removing it is like ripping off the bandages and reopening a wound," she says.

"I was taught, don't mess with people's graves," she adds. "This is sacrilege - it's wrong, it's illegal, and it's immoral."

She quotes President Woodrow Wilson, who said in his speech at the statue's unveiling in 1914 that a monument like this could only happen in a democracy.

"He [said] in most places the losers... basically get themselves turned into slaves, and subjugated or killed. But in our country, we reconcile, and we build a memorial for reconciliation."

Aside from the cultural or moral concerns, there's the problem of how to actually remove a 32ft (10 metre) tall statue made of granite and bronze.

In December, Richmond in Virginia - southern capital in the Civil War - removed the last Confederate monument owned by the city and took it to a civil rights museum on a lorry

Once it is removed, what becomes of it is unclear: an NBC report from 2020, external states that of 130 monuments removed, just 35 were moved to new homes - often museums or Confederate cemeteries. The remainder likely end up in storage, as none come forward to take them.

The statue would be the first war memorial that has ever been removed from Arlington. The Department of Defense says it must be removed by 1 January 2024 at the latest, "as it offers a nostalgic, mythologized vision of the Confederacy".

The same words are on an educational plaque near the statue, which adds that the monument features "highly sanitized depictions of slavery".

The cemetery installed that plaque in 2020, before the decision to remove the statue. "Most tour groups do not have the background to properly contextualize the Memorial," Ms Meeker says.

A public consultation is due to begin in the autumn of 2023, to determine what to do with the memorial once it is gone.

Defend Arlington however hope it can be legally stopped before the 1 January deadline for its removal.

Even Dr Ezekiel and her family were torn about what they wanted done with it, when they wrote their protest letter.

"Some people wanted it ground to dust and thrown away. Others said no, it needs to be in a museum because it's a piece of art. Others still said it needs to be in a museum because it's a part of racist history that needs to be shown.

"I don't like it artistically. But, you know, it can't be denied that he was a great sculptor."

- Published21 April 2021

- Published17 August 2017

- Published9 August 2018