Why the fuss over Confederate statues?

- Published

Statues of generals Lee and Jackson in Baltimore were removed earlier this week

It's been over 150 years since the last shots were fired in the US Civil War, but a debate still rages over how history will remember the losing side.

Hundreds of statues dedicated to the Confederacy - the southern states which revolted against the US government - exist all throughout the United States, and often serve as an offensive reminder of America's history of slavery and racial oppression.

Recent decisions by local governments to remove those memorials has triggered a backlash from a vocal group of Americans who see their removal as an attempt to subvert US history and southern culture.

President Donald Trump waded into the debate on Thursday, tweeting that the controversial monuments are "beautiful" and bemoaning that their beauty would be "greatly missed" from cities.

When were they erected?

Most Confederate monuments were not built until nearly a generation after the war ended in 1865, mostly due to a lack of funds during the Reconstruction era.

It was not until the turn of the century, as southern states began to enact so-called Jim Crow laws designed to deprive recently freed slaves of equal rights, that the monuments began to go up in public spaces.

Democrats have called for Confederate monuments to be removed from Capitol Hill in Washington

The second wave came in the 1950-1960s, as civil rights campaigners demanded desegregation and equal rights for African-Americans.

"The civil rights movement led to a backlash among segregationists," according to a report by the Alabama-based Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which tracks hate groups and civil rights movements.

To date, there are over 700 monuments to the Confederacy - most, but not all, located in the South.

New Orleans mayor on why Confederate monuments have to go

Who do they depict?

Some memorials are dedicated to the foot soldiers of the Confederacy, and many depict famous generals such as Robert E Lee or Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson.

Descendents of Jackson on Wednesday called for depictions of their relative to come down in the Virginia state capitol, saying that the white supremacist protest in Charlottesville "showed us unequivocally that Confederate statues offer pre-existing iconography for racists".

The phrase "Monuments Must Go" began trending on Twitter, external in the US, as users shared the descendants' open letter to Richmond officials.

After the Unite the Right rally, which was comprised of Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazi supporters, Robert Lee's great-great grandson condemned "the misuse of his memory by those advancing a message of intolerance and hate".

The far-right marchers had nominally come to the university town to protest against the city council's decision to remove a statue of Lee.

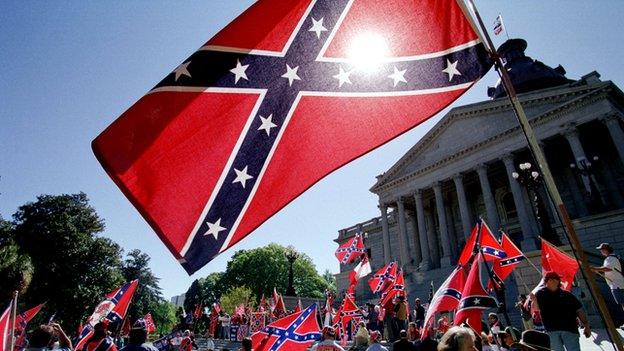

Critics see Confederate monuments as racially offensive

Why are they controversial?

Most defenders of Confederate symbols say they are not meant to memorialise slavery, which the South fought to preserve.

They say that the war was fought for "state's rights" and against the federal system, adding that symbols such as the Confederate "battle flag" commemorate the region's history and culture.

But most historians agree it was about slavery. Racial minorities, especially black Americans, feel that their presence in public life is offensive.

Maine Governor Paul LePage said on Thursday that removing them would serve simply to whitewash history.

"How can future generations learn if we're going to erase history? That's disgusting," Mr LePage told WGAN radio, adding that removing them is "just like" removing monuments to the 11 September 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon.

"To me, it's just like going to New York City right now and taking down the monument of those who perished in 9/11. It will come to that," he described.

Mr Trump has also applied this argument, saying that it will only be a matter of time before liberal activists suggest removing monuments to Thomas Jefferson or George Washington, because they owned slaves.

Racism in the US: Is there a single step that can bring equality?

Why are they being targeted now?

In 2015, only days after the 150th anniversary of the Civil War was commemorated, a white man killed nine parishioners in an African-American church in South Carolina.

Photos of the man posing with Confederate flags changed how many Americans viewed the emblems.

No longer were they considered harmless symbols of culture, commemorating a rebellious spirit.

After the South Carolina government chose to remove the Confederate flag from the state capitol, many local governments followed suit by removing their own images.

Now a second wave of removals are happening, sparked by the violent events in Charlottesville.

Just this week, vandals have targeted them in Ohio, North Carolina, and Maryland.

But some states such as North Carolina, where this week angry crowds tore down a bronze statue of a soldier, have laws preventing local governments from removing the monuments without higher approval.

In a Marist poll conducted this week, external, 62% of Americans believe they should remain "as a historical symbol", and somewhat surprisingly, 44% of African-American respondents agreed.

- Published23 December 2015

- Published16 November 2016

- Published30 August 2013