The Supreme Court flexed its conservative muscles. What comes next?

- Published

The Supreme Court's latest term has finished - and featured a few surprises beyond the headline cases

The Supreme Court ended its term this week with a flurry of decisions that underlined the sharp political and ideological divides between the six conservative judges and their three liberal counterparts.

President Joe Biden described it as "not a normal court" - saying it was willing to reverse longstanding precedent to advance its ideological agenda.

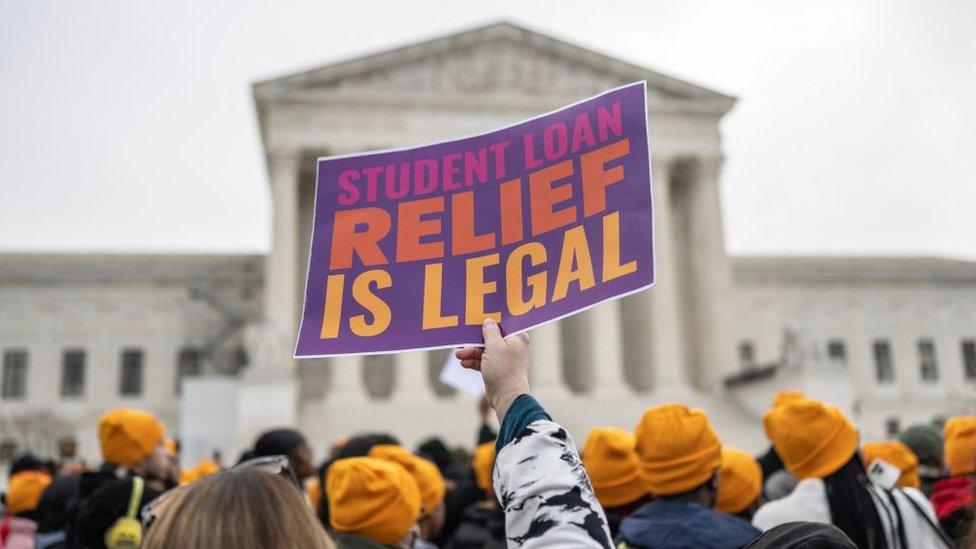

The six conservative, Republican-appointed justices stuck together to block Joe Biden's student loan forgiveness plan, to bar US universities from considering race in their admissions process, and to allow creative professionals to refuse to work on material that promotes gay marriage. The three liberal, Democrat-appointed justices could only write stinging dissents.

It comes on the heels of last term's landmark decisions striking down abortion protections, limiting the scope of environmental regulations, and expanding gun-ownership rights - all also decided by the same six-to-three margin.

But beneath the headline cases, there has been some nuance - and a few surprises - in the court's decisions this term. In some cases, conservative justices did side with their liberal colleagues to form a majority that curtailed some of the more ambitious Republican priorities - for example on aggressive immigration enforcement, and strengthening state power versus the federal government.

The court sustained Mr Biden's immigration policies which prioritise the deportation of undocumented migrants who have committed serious crimes or recently arrived in the US.

It upheld provisions in the Voting Rights Act, a landmark piece of civil rights legislation from the 1960s that required states to ensure that minorities have representation in Congress and legislatures that is equivalent to their overall population.

It refused to endorse a right-wing theory that state legislatures have sole power to run elections - a proposal that could have allowed states to overturn the results of any future presidential election.

University of Texas law professor Steve Vladeck says decisions like these expose differences within the conservative justices on the court. Some are more closely aligned with the more "traditional" conservative legal world from before President Donald Trump, while others side with the Republican Party's current agenda.

On issues such as abortion and gun control, he says, all the conservatives were closely aligned. "No one should confuse this court with the word moderate," he says. "But there is a distinction between the median justice and the sort of justice who I think is further to the right."

Given that conservatives control the court majority, these divisions could come into play when the new term begins in October. The court is set to hear several potentially landmark cases that involve the US right trying to limit what it views as the sprawling power of the federal government.

The first is a challenge to the legality of the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau, a consumer-rights agency established by Democrats after the financial collapse of 2008.

Another involves a longstanding court precedent that gives power to government agencies to interpret how laws are applied and enforced.

In this term's student loan case, as well as a decision last year involving how the Environmental Protection Agency could regulate greenhouse gas emissions, the court pared back the freedom of agencies to enact sweeping new policies.

Next term, the court could go further in stripping the power of what many conservatives call the "administrative state", setting a precedent that would make it even harder for presidents and their political appointees to bypass congressional gridlock and achieve policy goals.

Related topics

- Published30 June 2023

- Published30 June 2023

- Published29 June 2023

- Published29 June 2023